“Being editors is not the best way to wealth. We all feel this now, and highwaymen are not respected the way they used to be.” – The Story of the Treasure-Seekers (1899)

The late Victorian and Edwardian Era children’s novelist Edith Nesbit was a committed socialist who defied Victorian social conventions by not marrying her lover, Hubert Bland, until she was seven months pregnant. She then lived in an open marriage, welcoming Alice Hoatson, one of her husband’s many mistresses, into her home and adopting her children, while conducting various affairs of her own, including one with (allegedly) the playwright George Bernard Shaw. Nesbit and Alice Hoatson wrote passionate love poetry to each other, and Hoatson worked as Nesbit’s trusted secretary, housekeeper and assistant, staying with her for some years after their husband/lover died. It is possible that Hoatson and Nesbit were also physically intimate, especially since Nesbit had strongly emotional, romantic attachments to other women, and Nesbit most definitely did not welcome some of her husband’s other mistresses into her home, but no one can be sure.

But Nesbit’s life was not all sexual scandal: she had a successful career as a writer, researcher and lecturer on economics (the latter sometimes on her own or with her husband), and helped found the Fabian Group, a precursor to Britain’s current Labour Party.

Nesbit did not turn to children’s literature in the hopes of sparking a revolution; she and her family needed money, and she wrote her children’s novels with a careful eye towards easily offended public opinion. But not surprisingly, given her background, many of her children’s novels proved provocative indeed. Like L. Frank Baum, her fellow writer across the pond, Nesbit proved gifted at inserting sly, anti-establishment and even revolutionary concepts into her children’s fiction. And, like Baum, she refused to write moral tales: instead, she worked defiantly with fairy tales and fantasy, and refused to sentimentalize children. Her children can be greedy, misguided, morally dubious, and quarrelsome, and even when well-intentioned, they are rarely good.

Except for the fantasy, all of this would be displayed in her very first children’s novel, The Story of the Treasure Seekers. Ostensibly the story of the six Bastable children and their attempts to restore the family fortune, the novel is a masterpiece of sarcasm, containing scathing indictments against newspapers that advertised “get rich quick” and “work at home” schemes (not new to the internet, alas), editors, bankers, politicians, literary fiction, the pretensions of British society and pretty much the entire British capitalist system. (Rudyard Kipling, however, is spared, which is nice, and in a sequel Nesbit was to say nice things about Wellington and Lord Nelson. So she wasn’t against everything British, and in some later books seems fairly pleased with British colonial rule.)

The novel is narrated by the not-always pleasant Oswald Bastable. (Oswald claims he will not tell which of the six children is narrating the story, but his combination of arrogance and desperate need for approval allows attentive readers to guess his identity by about page 30.) The use of this child narrator allows Nesbit to pull off a neat narrative trick. Oswald is truthful, but not particularly perceptive, and readers can easily read through the lines to see, shall we say, alternative explanations. In an early example, Oswald airily tells us that a confused servant took off with his sister’s silver thimble entirely by mistake:

We think she must have forgotten it was Dora’s and put it in her box by mistake. She was a very forgetful girl. She used to forget what she had spent money on, so that the change was never quite right.

.Right.

Nesbit employs this technique to show readers a very different reality than what Oswald allows himself to see. It not only adds to the humor, but also allows Nesbit, through her arrogant, imperceptive child narrator, to make many of her fiercest denunciations against British society in an almost safe space—and convey a not so quiet warning to the English middle class, her most probable readers.

After all, the Bastables were once middle-class, employing various servants, eating and dressing well, until the death of their mother and illness of their father. His business partner took advantage of the situation to take the remaining money and flee to Spain, and the family is now poverty stricken, deserted by almost all of their friends, and hiding from creditors.

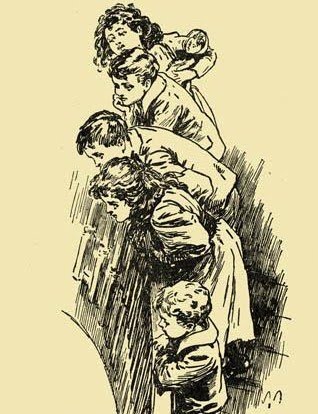

The Bastables seem to take this in stride, to the point where a careless reader might misunderstand the family desperation. After all, they still have a house, a small back garden, a servant, and food. But a closer reading shows that their ability to keep the house is severely questioned—creditors plan to seize it. The father is almost always gone, either hiding from creditors or hunting for money. The servant, Eliza, is shouldering the burdens of housekeeping, cooking, and childcare—none of these a joke in days before appliances, without another adult in the house. Eliza is also a terrible cook, but they cannot afford a replacement. Dora, the oldest sister, breaks down as she attempts to parent her siblings and mend their clothes. The Bastable father is feeding his family only by dint of buying goods without paying for them—and then hiding when the infuriated butchers and shopkeepers come to call, although the local butcher softens a little when he realizes that the Bastable children have resorted to a get-rich/earn money at home scheme, and that the furniture, carpets and clothes are in tatters. The family silver has been sold. (Oswald thinks it’s just getting cleaned.)

And although Oswald stoutly informs us that he’s fine with wearing clothes with holes in them, his constant mention of them strongly suggests otherwise. He is aware that, as the oldest boy, he holds a certain responsibility, but his middle class roots prevent him from taking some jobs, and thus, he and his siblings take on increasingly more desperate schemes to restore the family fortunes.

I’ve made matters sound dreary, but this is the part that’s laugh out loud funny, partly because the schemes almost always go completely and terribly wrong, partly because Oswald continually misinterprets everything while loudly proclaiming his inherent superiority to all living creatures. It does not take long for an alert reader to note that his bragging masks some major self-esteem issues: after all, within the space of a few years, he’s gone from a relatively pampered middle-class child with a supposedly secure future to a poor child terrified that his father will be snatched away from him, and with no clear future at all. And although, as I’ve noted, he’s not terribly perceptive, he’s perceptive enough to know that his father is not telling him the complete truth—and feeling terribly hurt as a result. And some of his opinions, particularly his pointed comments on literature and how to write books and the more pointless conventions of society, are spot on. So I probably shouldn’t be laughing at him, but I am.

But if using Oswald as a voice allowed Nesbit to voice some of her impatience with the foibles of society, literature, and editors, she saves her fiercest satire for the plot. For what, in the end, does save the fortunes of the Bastables? Not any of their (many) attempts at capitalism, hard work, careers, or highway robbery/kidnapping, but a dowsing rod and two acts of charity and kindness. In fact, the more traditional and capitalistic their approach, the more trouble the Bastables get into. The lesson is fairly clear: investment, capital speculation, and hard work get you into trouble. (Although, to be fair, hard work, not as much.) Sharing your assets bring rewards.

That’s a fairly powerful message—although, to be clear, the worst results come from the Bastables’s attempts at investment and speculation, not hard work, which typically only creates minor problems.

Frankly, my sense is that The Story of the Treasure Seekers may be entirely wasted on children. (This is not true of Nesbit’s other works.) I know I found it—well, specifically, Oswald—annoying when I first tried to read the book when I was a kid. This read found me laughing on nearly every page—and wanting to urge every grown-up I knew to give it a try.

Mari Ness was sorry to learn that get-rich quick schemes didn’t work in the Victorian era, either. She lives in central Florida.