Although author of over one hundred books, it was rare for John D. MacDonald to leave the fertile stomping ground of his native Florida. Like his characters, he clearly felt uncomfortable in the big Northeastern cities or windswept Texan plains. However, in his novels set in Las Vegas, MacDonald harnesses that discomfort to write two works of almost perfect noir.

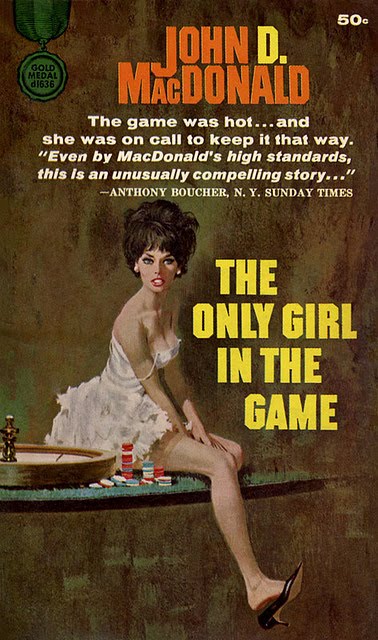

The Empty Trap (1957) and The Only Girl in the Game (1960) are both better remembered for their lusty Robert McGinnis cover art than their content. The similarities don’t stop there. In both books, the protagonists are young hotel managers, working in Las Vegas and wrestling with the unpleasant awareness their hotels are owned by the mob.

The plots are similar as well. In each, the square-jawed, broad-shouldered, straight-laced hero falls for the wrong girl and tries to fight the mob. In The Empty Trap, this is Sylvia, the young wife of the hotel’s Syndicate owner. In The Only Girl in the Game, the femme is Vicky, a lounge singer and (cough) extra-hours employee of the casino. In both books, the forbidden love between the Square Jaw and the Reluctant Mob-Moll serves to pull the trigger on the action.

However, despite their identical trappings, the books explore the noir world in different ways. The Empty Trap is a simple revenge story. It begins with Lloyd Wescott, Square Jaw, plummeting off a cliff. He’s tried to get away from the mob with both cash and girl and, judging by his opening position (falling), the attempt failed.

Lloyd’s story reveals one of the rudimentary principles of the genre: he’s an imperfect protagonist in an imperfect world. Lloyd’s own recognition of this dark truth is the most compelling part of the book. He begins the book knowing “that he was one of the good guys. That made it simple, because then you always knew how it came out…. But something was wrong with this script [he wasn’t saved] in the nick of time. The nick of time went right on by while you screamed and screamed onto a bloody towel.” (33)

Even after the book’s violent opening lesson, Lloyd still feels disassociated from his situation. From white collar poster child to broken-bodied field worker is a hard reality to face, but he gradually realizes that that “a thing cannot be black or white” (44). There’s no moral component to his suffering. Lloyd did bad things and he did them to bad people. The two don’t balance out; simply because there is no cosmic balance. The repercussions for his actions don’t equate to a judgement. Lloyd doesn’t need to be good in this world—he needs to be strong.

Most of these life lessons are imparted to Lloyd as Miyagi-like snippets of wisdom by sage villagers in rural Mexico. Lloyd, armed with a new identity, a sense of purpose and the preternaturally wiry strength of a man who once got chucked off a cliff, heads back to the casino and wreaks predictable mayhem. The Empty Trap concludes with his retreat from society, as Lloyd returns to the wilderness to lick his wounds. The book’s defining moments are limited to the early pages, when its bed-ridden protagonist has the slow-building epiphany that life isn’t fair.

Although ostensibly covering the same theme of karmic inequity, The Only Girl in the Game comes to a more advanced conclusion. It isn’t that life is unfair; you’re just living it wrong.

Hugh Darren, this book’s incarnation of the Eternal Square Jaw, is a compulsive champion of order. Hugh knows the rules. He runs the hotel, he carefully saves his income, he gets funding from the appropriate backers and then he’ll have a place of his own. Our Hugh’s a clever boy with everything figured out.

Naturally, it all falls apart. One by one, Hugh is stripped of his illusions. First, a close friend succumbs to the deadly lure of the casino’s tables. Then, Hugh learns that the mob is carefully spying on his hotel’s guests. Finally, when Vicky’s dodgy extracurriculars are revealed to him, Hugh realises that all he holds sacred is a lie. His world isn’t governed by fair play; it is ruled by the shadowy physics of greed and favoritism.

The casino itself is an example of how things really work. There are the ostensible owners—which include famous film stars. However, even these smiling faces are kept in check with their secret vices. The casino’s real owners are the faceless businessmen of the Syndicate. Every dollar winds up in their pockets and every favor winds up written in their books. MacDonald gleefully details the omnipotence of the mob administration as they glean their pounds of flesh from the unwary.

When Hugh tries to battle the mob using the tools he knows—law, reason, loyalty—he fails. Fortunately, he’s a quick study. His first awakened act is a symbolic one—he sabotages the operation of his own hotel in order to convert loyal employees to fearful informers. With this sacrifice, Hugh’s metaphorically pulled up a chair, ready to play. Hugh embraces savagery as he tortures, blackmails and murders his way through Vegas. There’s no morality in his actions, but there is a crude justice. Unlike Lloyd, Hugh ends the book as a fully enlightened part of the shadow system—ready and willing to fight the Syndicate on their own terms.

If The Empty Trap is about how the world doesn’t work in noir, The Only Girl in the Game illustrates how it does. For all his macho bravado, Lloyd can only escape the darkness. Hugh embraces it and thrives. In neither case does MacDonald judge his protagonist or their ultimate decision, instead, he reserves all his scathing criticism for the sickening world in which they live. The bright lights of Vegas may appeal to some, but John D. MacDonald was far more interested in the shadows they cast.

Jared Shurin gleefully snarks for the geek culture blog Pornokitsch. He’s currently editing two books on the apocalypse, including an anthology of original fiction (with Anne C. Perry). He’s from Kansas City and is a trained BBQ judge.

I skipped all but the first paragraph, because I really like John D. MacDonald’s Travis McGee and Area of Suspicion (set in Florida and an uncomfortable Ohio (I think), respectively) and will now look for these.

I’m actually partway through Dress Her in Indigo on my own little re-read.

Thanks!

Indigo might be my favorite, although the ending is (per usual for the Travis series) a little goofy. I really enjoy the Mexican setting though, as well as MacDonald’s portrayal of the burned-out expat life.

Perhaps but notice that John D. MacDonald was hardly a native to

Florida however much sand he had in his shoes. Likely enough he was uncomfortable in the big Northeastern cities or he would have stayed and prospered as the Harvard Business School MBA he also was.

Two things. First. The TV show The Pretender did a comic variation of this theme – even starting with Jared, chained and weighted, being pushed off a pier. This was one of the Argyle episodes.

Second, since you pointed out the cover art. Another great artist of this style and period was James Avati. His work is worth looking into. The lusty ladies are there but he was also great at setting up stories in his art.

@Clark: Amazing, isn’t it? Especially considering how often Travis rails against the outsiders that are all moving to Florida, not appreciating it, and ruining the coast/wetlands/boats/scenery. JDM wasn’t a native, but certainly did his best to identify as such…

@Ludon: I love the James Avati covers – his edition of 1984 is one of my favorite paperbacks of all time. You’re absolutely right: he’s not only mastered the curvy cover figure but his work also does a bit of storytelling (his cover of “If He Hollers…” is another one of my favorites for that very reason)

First, let me congratulate you on an well-written comparison of these two books. Steve Scott’s Trap of Sold Gold blog sent me your way.

But (you knew that was coming), I must take issue with your statement that JDM “clearly felt uncomfortable in the big Northeastern cities”. Many of his novels and short stories were set in the Northeast; that is where he lived before he came to Florida. A few off the top of my head are Area of Suspicion, All These Condemned, A Bullet for Cinderella, Clemmie, You Live Once, The Neon Jungle, Weep for Me, and yes, Travis McGee in Nightmare in Pink. The fact that he didn’t care much for the Northeast doesn’t mean he didn’t feel comfortable writing about them.

This is a minor point. I really did enjoy your article and would like to link to it the next time I post a cover image of Empty Trap or Only Girl on my blog.

“The fact that he didn’t care much for the Northeast doesn’t mean he didn’t feel comfortable writing about them”

You’re absolutely right – and that’s very well-phrased.