This is not the book I’d meant to review, but it was due back to the library…and as I started reading, I discovered that it had story after story after story of material that would fit the QUILTBAG+ Speculative Classics series. I love it when that happens, and I am happy to share this sense of discovery with you!

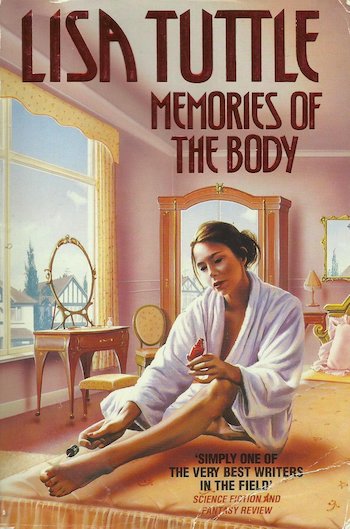

Memories of the Body: Tales of Desire and Transformation was published in 1992, featuring reprints of stories originally published in the late 1980s or earlier. It is a collection of mostly contemporary horror stories themed around bodily transformation, often related to gender, and dealing with complex feelings. The feelings involve not just desire as in the title, but also jealousy: a form of difficult desire, and one that stories often elide because it is uncomfortable to consider. Lisa Tuttle goes all-in on that discomfort, and a sense of unease that shades quickly into horror.

I don’t always review single-author collections in linear order, story by story, but here the thematic arc seemed very clear to me, so I’m going to proceed in that order. The book starts with “Heart’s Desire,” a piece that initially seems to follow a woman stalking her friend’s ex-boyfriend—a heterosexual interaction that’s bloodcurdling, but still not particularly speculative. But the story eventually turns into something gender-bending, in a way that’s unexpected even for the characters. I haven’t seen this story mentioned in a trans context, and at first I was wondering if that could be because (without explaining the plot in detail) the gender aspects were part of the twist. But as I went on to read more pieces that could be categorized as trans-related in some way, I realized that in the late Eighties-early Nineties, most readers of SFF did not remark on this topic. One of the first SFF novels about trans themes (co-)authored by a writer who was out as trans at the time of writing, Nearly Roadkill (see my review!), was published in 1989, and not by an SFF press—and likewise was not part of an extended SFF discussion, by and large.

The following piece, “The Wound,” also turns out to be trans-related, and could be a contemporary love story if not for the fact that it’s set in a secondary world where all people are born as men. When two people end up in a relationship, the more submissive partner changes biologically and turns into a woman. The change is both irreversible and socially stigmatized; the protagonist struggles mightily with it at the same time as wanting it, in some way. This is not a romance; it doesn’t end well. But it’s also not a simple gender/sex-essentialist story. It is full of subtlety, and it also has queer people who are trying to eke out an existence in a world constrained differently by biology than ours. It made me want to read on, in hopes of seeing more of this transformation theme.

The next story, “Husbands,” is a series of vignettes about masculinities and also, to a great degree, humans as animals. The middle vignette might be the most relevant to present-day issues: men vanish, but the children of a new generation reinvent gender. The adult women speakers present this as negative and restrictive, in the fashion of some kinds of trans-exclusionary feminisms that call for gender to be abolished, but I was wondering about how the speakers’ kids would experience their newfound gender. Ultimately the story suggested a more positive reading of gender instead of a pessimistic one, even if the positivity was not currently available to the protagonist: “I felt such longing, and such hope. I wished I were younger. I wanted another chance; I had always wanted another chance.” (p. 58)

The more explicitly gender-bending block ends here, and the following tale, “Riding the Nightmare,” is a more straightforward story about a woman and a terrifying, ghostly mare. “Jamie’s Grave” is also more conventional horror, but it’s an especially strong entry; I’ve read it before, anthologized elsewhere. (ISFDB lists at least seven reprints of this piece, but I’m sure I read it in an eighth—maybe in Hungarian?) The child Jamie has an imaginary playmate residing in the backyard…but is it truly imaginary? What elevates this story is not the theme, done many times before and after, but the emotionally resonant portrayal of motherhood and childhood, with its chilling overtones.

The following story, “The Spirit Cabinet,” engages with Victorian spiritualism and offers a twist involving the mechanics of it that I found more believable than the usual ghosts. Here again, the husband-wife relationship is what makes the piece shine well beyond the twisty SFnal conceit.

Buy the Book

Docile

“The Colonization of Edwin Beal” tackles the difficult trope of a protagonist who is not only unlikeable, but who is supposed to be a bad person: “Edwin Beal was looking forward to the end of the world” (p. 118)—we find out in the very first sentence, and it goes downhill from there. (Or uphill, because demonstrating this terribleness is clearly what the author wanted to achieve.) This is not one of the most subtle stories in the collection, but I oddly enjoyed how it ended.

We return to the gender-y bits with “Lizard Lust,” a story about people from a different dimension where the aggressively patriarchal gender roles also require the men to be in possession of a lizard. Women can’t have lizards—or can they? When someone from our world ends up in theirs, events take an even more brutal turn. This is possibly the most explicitly trans story in the book, with pronoun changes, etc., and clearly the author is invested in the topic beyond a quick thought experiment, but ultimately some of the other stories worked better for me, possibly because here we see a quasi-trans-man character as a domestic abuser.

“Skin Deep” also has some lizard-like aspects, involving an extraterrestrial (?) woman who sheds her skin, meeting a young American tourist similarly out of his element in France. “A Birthday” edges gently toward bizarro horror, featuring a woman who can’t stop bleeding through the pores of her skin; this also seems connected to gender, but without gender-transgressive elements per se. As is also the case in “A Mother’s Heart: A True Bear Story,” where a giant bear in the backyard (again, that locus of what should remain hidden?) fulfils the wishes of a family in conflict. But who gets the best outcome: the mother, the father, the children, or…? “The Other Room” is also about childhood and memory, this time from an older man’s point of view, as he looks for a hidden room in an old house. “Dead Television” tackles memory with one thoroughly executed SFnal idea: a way for dead people to communicate with the living, in a unidirectional way, like television.

“Bits and Pieces” was another of the standouts of the collection for me: a woman finds warm, healthy pieces of her ex-lovers in her bed. The plot starts out as eerie but oddly comforting, then it takes increasingly grisly turns, as things devolve to rape and murder. I’ve read a number of rape stories recently where the victim has zero agency, and this one wasn’t like that—though you should be warned that it is still a horror story and it ends the way horror stories generally do. This one had no particular queer aspects, but it is definitely gender-related and important; also, it’s interesting to see a horror story, with bodies, where the horror doesn’t necessarily come from the body aspects per se, but rather in what people do to deal with the situation. This is not the usual take on body horror, and that was refreshing to see.

The titular “Memories of the Body,” the capstone story of the collection, also involves bodies, horror and womanhood, but in a way that reflects on classic science fiction. In the future, technology exists to create realistic technological replicas of people—which we’ve seen in many, many stories. But here, the focus is on a controversial form of psychotherapy that involves achieving catharsis by killing a replica of your abuser. This goes about as well as you might expect…

I enjoyed this collection, and I felt it strained with much muscles against the restrictions of second-wave feminism, pointing the way toward the third wave. In addition to the transgender themes, asexuality also kept cropping up, though it was less firmly a specific theme. I am always glad to see a focus on domesticity and everyday life in SFF, and here Lisa Tuttle ensures that this focus leaves a lasting, often terrifying impression. It made me wish to read more of her work. I was first exposed to feminist speculative fiction when, many years ago, I found a used copy of Tuttle’s A Spaceship Built of Stone, and then rapidly went on to buy up all the Women’s Press SFF titles—I still have the book and I should probably reread it. Additionally, one of Tuttle’s other short story collections, A Nest of Nightmares has just been reissued by Valancourt Books: with the terrifying original cover, no less. I would like to hope that eventually a new edition of Memories of the Body will follow.

Next time I’ve found something very unique to share with you: a queer poetry collection with speculative themes from 1995—the first poetry volume I will have covered in this column! What unexpected discoveries have you made lately?

Bogi Takács is a Hungarian Jewish agender trans person (e/em/eir/emself or singular they pronouns) currently living in the US with eir family and a congregation of books. Bogi writes, reviews and edits speculative fiction, and is a winner of the Lambda Literary Award and a finalist for the Hugo and Locus awards. You can find em at Bogi Reads the World, and on Twitter and Patreon as @bogiperson.