Talia is a gnome, complete with bountiful garden and a penchant for wacking you over the head with a shovel. Theodore is a wyvern that is as happy to add a button to his hoard as a coin. Phee, a forest sprite, might be distrustful, but she can create beauty in the blink of an eye. Sal is sometimes a large boy and sometimes a small dog, but always a poet and always braver than he seems. No one’s sure what Chauncey is, only that he’s a formless blob with aspirations to become a bellhop. And Lucy, well, Lucy is the antichrist.

At Marsyas Island Orphanage, all are welcome—regardless of how you look or if your dad is the literal devil. This is something that Linus Baker, caseworker for the Department in Charge of Magical Youth (DICOMY), learns fast during his time there. He learns a few other things too: like what the ocean looks like and how to go on an adventure. Like how to fall in love with something (and someone) other than his job. TJ Klune’s The House in the Cerulean Sea is a whimsical queer love story that pits bureaucracy against found family. It is a novel as funny and charming as the misfit kids that graces its pages, and as sweet as the beating heart at its center.

The plot of Cerulean Sea is simple and sweet. When Linus arrives on Marsyas Island, he is ready to treat the job of investigating Arthur Parnassus and his orphanage just like any other job. He has his DICOMY book of rules and regulations, his cat, and complete and utter faith in the system in which he works. As he gets to know the kids, though—their dreams and their traumas, their total isolation from a world that fears them—he starts to see how the rules and regulations have failed them. And as he gets to know Arthur—his secrets and his boundless love for the children in his care—Linus finds it all but impossible to be “impartial” in his reports back to head office. He finds himself fighting on the orphanage’s behalf—first against the bigoted mainlanders next door to Marsyas and later against the institution that signs his paychecks. The inhabitants of Marsyas—and the reader—know all along that Linus has the capacity to do right by the magical children he works for. The question is whether he’ll do right by himself.

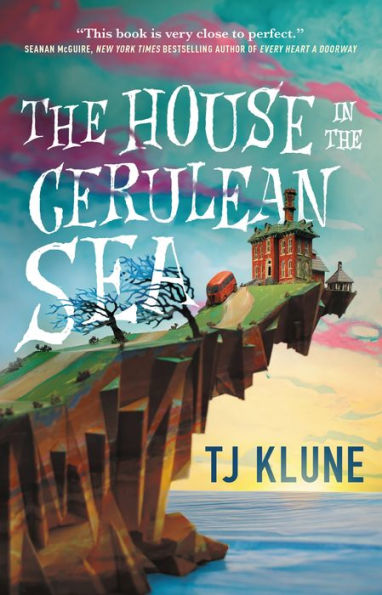

Buy the Book

The House in the Cerulean Sea

With such a simple premise, it’s inevitable that the characters drive the story, adult and child alike. Klune does a remarkable job of making you care about these kids in short order. Linus himself is rightfully frustrating but funny enough to make up for it. Arthur, though, who is very much the heart of the story, is specifically designed to sink readers like yours truly (which is to say queer millennial nerds). It’s like all the Harry Potter fanfiction that asked “What if Remus Lupin were headmaster though? Like an actual good teacher that cares about his students? With a dark backstory that still resolves into kindness and resilience?” finally made good. The romance that threads throughout the story flows naturally because who wouldn’t fall in love with Arthur?

The romance, of course, is not the point of it all: The House in the Cerulean Sea is first and foremost a story about seeing each other as people, and, once we’ve got that part down, just what our responsibility to other people is. But besides viewing magical children as worthy of love and respect, it feels particularly special that Klune treats his young characters as worthy, not just as “but what about the children”-type stand-ins, but as complex beings with their own identities. In fact, a huge amount of emphasis is placed on the fact that these kids grow up into adults, and we can’t just stop caring about them once they’ve left the orphanage. It’s a presentation of parenting and childhood that is quintessentially queer, focused as it is on holistic life rather than some mythologized vision of childhood innocence.

I think it’s worth noting, too, that the magical children are not presented as allegories for racial or sexual minorities—though of course there are parallels. If you’ve ever had to have a difficult conversation with a young person about how the world perceives them, this book will resonate. If you’ve ever been a young person looking for somewhere to belong, this book will resonate. But Klune isn’t treating these bizarre and mythical beings as stand-ins: Chauncey definitely is just precocious tentacled goo, and Sal is black and a shapeshifter both.

By virtue of its fairy tale-like qualities (the novel’s world building is ambiguous enough that you can map it onto any time and place you’d like), Cerulean Sea does tend to explain itself explicitly quite a bit and thus falls prey to didacticism. At any other time, the constant outright statements of “can’t we all just be decent people?” might grate on my nerves, but it’s March 2020, so I just nodded along muttering “yeah, why can’t we?” It’s nice to read something kind and good-spirited and sappy right now, and it’s nice to be reminded that there are many people in the world working to make it gentler and more compassionate. I don’t care that this borders on saccharine. Queers deserve to have a little sweetness, as a treat.

The House in the Cerulean Sea is available from Tor Books.

Em Nordling reads, writes, and manages research in Louisville, KY.