In Wet Magic, Nesbit temporarily abandoned her usual practice of allowing children to interact with magic while remaining in their own worlds—or at the least, magical worlds they had created, instead taking them to a strange new fairyland beneath the sea. (And if this reminds you of L. Frank Baum’s The Sea Fairies, which had come out two years earlier in the United States, you are not alone.) As experiments go, it is not an entirely successful one, however much Nesbit may have been aching for a change from her usual formula, or needing to release some hostile thoughts about other authors.

At first, that change is not apparent, since Wet Magic begins with four children just happening to find magic in their ordinary lives. By complete accident—magic, you know—the children just happen to have come across a spell that lets them see mermaids, and on their way to the seashore, they just happen to hear about a mermaid, and shortly afterwards—you can probably see where this is going—they just happen to hear news stories of a captured mermaid who has been taken to a circus. A rather terrible one: Nesbit sketches its inadequacies in a few brief sentences, making it clear that this is a circus that a) is in serious financial trouble, b) doesn’t provide any decent gingerbread, and c) isn’t any fun. (To be fair, when I was taken to the circus as a young child I didn’t get any gingerbread either, but I did get popcorn AND cotton candy AND a hot dog AND peanuts and was unsurprisingly incredibly sick later, but Nesbit is less worried about childish digestions and more concerned about the financial state of this circus.) AND the circus games are cheating their young customers, so obviously that even the children are aware of it. It’s just the sort of place where a captured mermaid might be found.

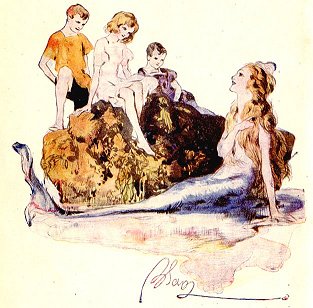

Alas, the mermaid turns out to be a very haughty, rather rude and not at all grateful mermaid indeed. But the excursion also introduces them to a boy named Reuben, who claims to be a “son and hare” of a noble line, kidnapped into the circus (the mermaid approves of this story) who helps them rescue the mermaid. And after this delightful first half of the book, the story slowly disintegrates into, well, a wet soggy mess.

To sum up, more or less, the children find themselves kidnapped to the mermaid’s undersea lands—her personality makes a distinct change, better for the children if not for the book—and then embroiled in a series of wars between the mermaids and other sea folk, and between Good and Bad Fictional Characters who just happen to have come out of books, the way characters do in magical lands, and a thoroughly inexplicable romance kinda thrown in from nowhere.

Unusually for Nesbit, this is all very—what’s the word I’m looking for—confusing. This had been an occasional problem in The Enchanted Castle and The Wonderful Garden, but rereading passages soon clarified matters. Here, well, it’s often difficult to know what’s happening in the second half of the book no matter how many times you reread it. Part of the problem is that, as the children eventually realize, the war is a completely pointless one; since no one is really fighting for any particularly good reason, it’s hard for anyone—including the author—to care much. Characters drift in and out of the narrative with no real explanation, and the occasional poetic touches only serve to add to the sense that this is nothing more than one of those confusing dreams that never does make sense.

And this even though so much of the book—particularly its first half—feels so familiar, thanks to the reappearance of so many of the regular Nesbit themes and tropes: the appearance of Julius Caesar, who by this point should have been demanding royalties; warm hearted but quarrelsome family relationships complicated by the arrival of a new outside friend; generally absent but well meaning parents; a slam against museums; the theme that magic is just around the corner, and multiple attacks on fellow writers. (This book’s first target: Marie Corelli. I can only shudder at what Nesbit would think to find out today that all of Corelli’s books can be found online, while some of hers cannot.) And Nesbit’s ongoing narrative asides to readers.

Not to say that Wet Magic has nothing new, even beyond the confusing second part in the undersea realms. This includes a new theme for Nesbit: environmentalism, as Nesbit, through both the children and her own narration, argues passionately against the “uglification” of English meadows and forests and seasides. By this, Nesbit is partly taking about urban development, something she and others in the early 20th century watched with dismay as England’s population continued to rise, and partly about littering, something Nesbit viewed as a growing problem, and partly about building ugly instead of beautiful things barbed wire instead of stone or wooden fences. But a key here is her anger against littering.

Nesbit also takes a moment to slam the uselessness of the British Royal Family—a rather new theme for her, perhaps reflecting the change in attitudes towards the British monarchy years after the death of Queen Victoria. (Or perhaps, Nesbit just felt that, her status as a children’s author safely established, it was past time to say something.) And she has one of her children deliver a powerful pacifist message—itself mildly chilling for readers knowing World War I broke out shortly after this book’s publication.

But these slightly new themes, and the comforting familiarity of the first part of the book, are just not enough to save it. Even the war between fictional characters feels more forced than amusing. Part of the problem is that when I originally read the book, I had not, as it happened, heard of Uriah Heep or Quentin Hayward, and even now, after years successfully avoiding the more saccharine tales of early 19th century literature, I can still say I have no idea who Mrs. Fairchild is without the aid of Google. (If Google is to be believed, Mrs. Fairchild produced children who were “prodigies of precocious piety,” which suggests I’m going to spend several more years successfully avoiding getting to know Mrs. Fairchild in a literary way.) And although I’m generally fine with missing or failing to understand obscure literary references, in this case, a certain condescending tone suggests that Nesbit despises me a little for not knowing them, which is rather off-putting—especially in a book which earlier suggested I would be safer not knowing their names. (Consistency is not this book’s strong point.)

And this time, rather than creating a cozy, friendly feeling, some of Nesbit’s narrative asides feel almost actively hostile: when explaining that she will not detail one of the battles between the Good and Evil People in books, for instance, she says, “But I have not time, and, besides, the children did not see all of it, so I don’t see why you should.” Because we’re reading the book?

An earlier narrative aside, “All this happened last year—and you know what a wet summer that was—” does perhaps suggest that Nesbit had given up hopes that anyone would be reading her children’s books in the distant future, which might explain part of the angst, but, still. (Or she just assumed that all British summers were wet, which I can’t argue with.)

And while this may only bother oceanographers, the book perhaps—well, more than perhaps—lacks something in geological and geographical accuracy, and I couldn’t help wishing that Nesbit had taken a moment or two to look up one or two basics about marine biology, and marine mammals and sharks in particular, and shown some awareness that porpoises are among the most intelligent creatures of the sea. I perhaps might have been more forgiving had I not been aware that L. Frank Baum had penned a tale just a few years earlier, using similar, but more accurate, puns about marine creatures, proving that the information was readily available even to non-specialists in the field.

One final note: this is another Nesbit book that occasionally uses offensive language and images, particularly regarding “savages” in lands outside England. That, with the other weaknesses of the book, leads me to say that if you are going to skip a Nesbit, let it be this one.

Mari Ness hasn’t yet managed to step into imaginary worlds, but she’s keeping an eye out for fantastic portals.