In American, demons wear white hoods…

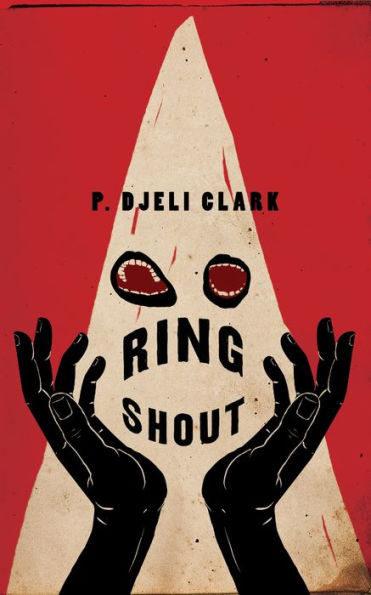

P. Djèlí Clark returns with Ring Shout, a dark fantasy historical novella that gives a supernatural twist to the Ku Klux Klan’s reign of terror—available October 13th from Tordotcom Publishing. Read an excerpt below!

[Warning: Contains explicit language that may be offensive to some readers]

In 1915, The Birth of a Nation cast a spell across America, swelling the Klan’s ranks and drinking deep from the darkest thoughts of white folk. All across the nation they ride, spreading fear and violence among the vulnerable. They plan to bring Hell to Earth. But even Ku Kluxes can die.

Standing in their way is Maryse Boudreaux and her fellow resistance fighters, a foul-mouthed sharpshooter and a Harlem Hellfighter. Armed with blade, bullet, and bomb, they hunt their hunters and send the Klan’s demons straight to Hell. But something awful’s brewing in Macon, and the war on Hell is about to heat up.

Can Maryse stop the Klan before it ends the world?

ONE

You ever seen a Klan march?

We don’t have them as grand in Macon, like you might see in Atlanta. But there’s Klans enough in this city of fifty-odd thousand to put on a fool march when they get to feeling to.

This one on a Tuesday, the Fourth of July, which is today.

There’s a bunch parading down Third Street, wearing white robes and pointed hoods. Not a one got their face covered. I hear the first Klans after the Civil War hid behind pillowcases and flour sacks to do their mischief, even blackened up to play like they colored. But this Klan we got in 1922, not concerned with hiding.

All of them—men, women, even little baby Klans—down there grinning like picnic on a Sunday. Got all kinds of fireworks—sparklers, Chinese crackers, sky rockets, and things that sound like cannons. A brass band competing with that racket, though everybody down there I swear clapping on the one and the three. With all the flag-waving and cavorting, you might forget they was monsters.

But I hunt monsters. And I know them when I see them.

“One little Ku Klux deaaaad,” a voice hums near my ear. “Two little Kluxes deaaaad, Three little Kluxes, Four little Kluxes, Five little Kluxes deaaaad.”

I glance to Sadie crouched beside me, hair pulled into a long brown braid dangling off a shoulder. She got one eye cocked, staring down the sights on her rifle at the crowd below as she finishes her ditty, pretending to pull the trigger.

Click, click, click, click, click!

“Stop that now.” I push away the rifle barrel with a beaten-up book. “That thing go off and you liable to make me deaf. Besides, somebody might catch sight of us.”

Sadie rolls big brown eyes at me, twisting her lips and lobbing a spitty mess of tobacco onto the rooftop. I grimace. Girl got some disgusting habits.

Buy the Book

Ring Shout

“I swear Maryse Boudreaux.” She slings her rifle across blue overalls too big for her skinny self and puts hands to her hips to give me the full Sadie treatment, looking like some irate yella gal sharecropper. “The way you always worrying. Is you twenty-five or eighty-five? Sometimes I forget. Ain’t nobody seeing us way up here but birds.”

She gestures out at buildings rising higher than the telegraph lines of downtown Macon. We up on one of the old cotton warehouses off Poplar Street. Way back, this whole area housed cotton coming in from countryside plantations to send down the Ocmulgee by steamboat. That fluffy white soaked in slave sweat and blood what made this city. Nowadays Macon warehouses still hold cotton, but for local factory mills and railroads. Watching the Klans shamble down the street, I’m reminded of bales of white, still soaked in colored folk sweat and blood, moving for the river.

“Not too sure about that,” Chef puts in. She sitting with her back against the rooftop wall, dark lips curled around the butt of a Chesterfield in a familiar easy smirk. “Back in the war, we always watched out for snipers. ‘Keep one eye on the mud, one in front, and both up top,’ Sergeant used to say. Somebody yell, ‘Sniper!’ and we scampered quick!” Beneath a narrow mustard-brown army cap her eyes tighten and the smirk wavers. She pulls out the cigarette, exhaling a white stream. “Hated fucking snipers.”

“This ain’t no war,” Sadie retorts. We both look at her funny. “I mean, it ain’t that kind of war. Nobody down there watching for snipers. Besides, only time you see Winnie is before she put one right between the eyes.” She taps her forehead and smiles crookedly, a wad of tobacco bulging one cheek.

Sadie’s no sniper. But she ain’t lying. Girl can shoot the wings off a fly. Never one day in Uncle Sam’s army neither—just hunting with her grandpappy in Alabama. “Winnie” is her Winchester 1895, with a walnut stock, an engraved slate-gray receiver, and a twenty-four-inch barrel. I’m not big on guns,but got to admit—that’s one damn pretty killer.

“All this waiting making me fidgety,” she huffs, pulling at the red-and-black-checkered shirt under her overalls. “And I can’t pass time reading fairy tales like Maryse.”

“Folktales.” I hold up my book. “Say so right on the cover.”

“Whichever. Stories ’bout Bruh Fox and Bruh Bear sound like fairy tales to me.”

“Better than those trashy tabloids you like,” I retort.

“Been told y’all there’s good info in there. Just you watch. Anyway, when we gon’ kill something? This taking too long!”

Can’t argue there. Been three-quarters of an hour now we out here and this Macon sun ain’t playing at midday. My nice plaited and pinned-up hair gone damp beneath my tan newsboy cap. Perspiration sticking my striped white shirt to my back. And these gray wool knickers ain’t much better. Prefer a summer dress loose on my hips I can breathe in. Don’t know how men stay all confined like this.

Chef stands, dusting off and taking a last savoring drag on the Chesterfield before stamping it beneath a faded Pershing boot. I’m always impressed by her height—taller than me certainly, and some men for that matter. She lean too, all dark long legs and arms fitted into a tan combat tunic and breeches. Imagine the kaiser’s men musta choked on their sauerkraut seeing her and the Black Rattlers charging in the Meuse-Argonne.

“In the trenches only thing living besides us was lice and rats. Lice was damn useless. Rats you could eat. Just had to know the proper bait and trap.”

Sadie gags like she swallowed her tobacco. “Cordelia Lawrence, of all the nasty stories you done told about that nasty war, that is by far the nastiest!”

“Cordy, you ate rats?”

Chef just chuckles before walking off. Sadie looks to me, mimicking throwing up. I tighten the laces on my green gaiters before standing and stuff my book into a back pocket. When I reach Chef she at the other end of the roof, peering off the edge.

“Like I say,” she picks up again. “You want to catch a rat, get the right bait and set the trap. Then, you just wait him out.”

Sadie and I follow her gaze to the alley tucked behind the building, away from the parade and where nobody likely to come. On the ground is our bait. A dog carcass. It’s been cut to pieces, the innards spilled out bloody and pink on the paving stones amid charred black fur. The stink of it carries even up here.

“You have to chop it up like that?” I ask, my belly unsettled.

Chef shrugs. “You want to catch bees, you gotta put out enough honey.”

Like how Bruh Fox catch Bruh Rabbit, I imagine my brother saying.

“Look like all we catching is flies,” Sadie mutters. She leans over the ledge to spit tobacco at the carcass, missing wide.

I cut my eyes to her. “Could you be more respectful?”

Sadie scrunches up her face, chewing harder. “Dog dead. Spit won’t hurt it none.”

“Still, we can try not to be vulgar.”

She snorts. “Carrying on over a dog when we put down worse.”

I open my mouth, then decide answering ain’t worth the bother.

“Macon not missing another stray,” Chef says. “If it helps, ol’ girl never saw her end coming.” She pats the German trench knife at her waist—her prize souvenir. It don’t help. We take to staring at the dog, the hurly-burly of the parade at our backs in our ears.

“I wonder why Ku Kluxes like dog?” Sadie asks, breaking our quiet.

“Seared but bloody,” Chef adds. “Roasted that one on a spit.”

“That’s what I’m saying. Why dog and not, say, chicken? Or hogs?”

“Maybe they ain’t got chickens where they from, or hogs—just got dogs.”

“Or something that taste like dog.”

My belly could do without this particular conversation, but when Sadie on a rant, just best ride it out.

“Maybe I shoulda put some pepper and spices on it,” Chef jokes.

Sadie waves her off. “White folk don’t care ’bout pepper and spices. Like they food bland as water.”

Chef squints over her high cheekbones as loud sky rockets go off, followed by the booms of gas bottle bombs. “I dunno. When we was in France, them Frenchies could put they foot on up in some food.”

Sadie’s eyes narrow. “You talking rats again, Cordy?”

“Not in the trenches. In Paris, where we was after the armistice. Frenchie gals loved cooking for colored soldiers. Liked doing a heap more than cooking too.” She flashes the wink and smile of a rogue. “Had us some steak tartare and cassoulet, duck confit, ratatouille—Sadie, fix your face, ratatouille not made from rats.”

Sadie don’t look convinced. “Well, don’t know what type of white folk they got in France. But the ones here? They don’t put no proper seasoning in they food unless they got Niggers to do so for ’em.” Her eyes widen. “I wonder what Niggers smell like to Ku Kluxes? You think Niggers smell like burnt dog to their noses, and that’s why they come after us so? I wonder if there’s even Niggers where they from? And if—”

“Sadie!” I snap, losing what little patience I got. “Heaven knows I asked you more than once to stop using that word. At least in my presence?”

That yella gal rolls her eyes so hard at me it’s a wonder she don’t fall asleep. “Why you frettin’, Maryse? Always says my Niggers with a big N.”

I glare at her. “And that make a difference how?”

She has the gall to frown like I’m simple. “Why with a big N, it’s respectful like.”

Seeing me at a loss, Chef intervenes. “And how can we tell if you using a big N or a common n?”

Now Sadie takes to staring at both of us, like we don’t understand two plus two is four. “Why would I use a small n nigger? That’s insulting!”

I can see Chef’s stumped now too. They could get all the scientists the world over to try and figure out how Sadie’s mind works—wouldn’t do no good. Chef soldiers on anyway. “So can white folk ever use a big N Nigger?”

Sadie shakes her head, as if this is all settled scripture written down between Leviticus and Deuteronomy. “Never! White folk always mean the small n! And if they try to say it with the big N, you should put they front teeth in the back of they mouth. Honestly, you two! What kind of Niggers even need to ask me that?”

I purse my lips up into their full rounded glory, set to tell her exactly what kind, but Chef holds up a fist and we drop to peer over the rooftop wall. There’s three Ku Kluxes entering the alley.

They dressed in white robes, with the hoods pulled up. The first one is tall and lanky, with an Adam’s apple I can spot from here. His eyes dart around the alley, while a nose like a beak sniffs the air. When he spots the dog carcass he slinks over, still sniffing. The two other Ku Kluxes—one short and portly, the other a broad-chested block of muscle—soon join him.

I can tell right off there’s something’s peculiar about them. Not just those silly costumes neither. Or because they sniffing at a chopped-up, half-burnt dog like regular folk sniff a meal. They don’t walk right—all jerky and stiff. And they breathing too fast. Those things anybody can notice, if they paying attention. But what only a few can see—people like me, Sadie, and Chef—is the way the faces on these men move. And I mean move. They don’t stay still for nothing—wobbling and twisting about, like reflections in those funny mirrors at carnivals.

The first Ku Klux goes down on all fours, palms flat and back legs bent so he’s raised up on his toes. He sticks out a tongue to take a long lick at the dog carcass, smearing his lips and chin bloody. A growl in the back of his throat sends a tickle up my spine. Then with a quickness, he opens his mouth full and plunges teeth-first into the carcass, tearing out and swallowing chunks of dogmeat. The other two scramble over on all fours, all of them feeding at once. It makes my stomach do somersaults.

My eyes flick to Sadie. She already crouched into position, Winnie aimed, eyes fixed, and her breathing steady. There’s no more chewing tobacco or any talk. When she ready to shoot, she can be calm as a spring rain.

“Think you can hit it from here?” Chef whispers. “They all so close together!”

Sadie don’t answer, gone still as a statue. Then, as a fierce thunder of firecrackers goes off at the parade, she pulls the trigger. That bullet flies right between the open crook of a Ku Klux’s bent elbow, hitting the dog carcass, and striking what Chef buried inside.

Back in the war, Cordy picked up the nickname Chef. Not for cooking—at least not food. Frenchie soldiers learned her to make things for blowing up Germans and collapsing trenches—like what she stuffed in that carcass. Soon as Sadie’s bullet punches through dog flesh, the whole thing explodes! The blast louder than those bottle bombs, and I duck, covering my ears. When I dare to peek back down, there’s nothing left of the dog but a red smear. The Ku Kluxes all laid out. The lanky one got half his face blowed off. Another missing an arm, while the big one’s chest look caved in.

“Lord, Cordy!” I gasp. “How big a bomb you put in there?”

She stands there grinning, marveling at her handiwork. “Big enough, I think.”

Wasn’t just blasting powder that took down the Ku Kluxes. That dog was filled with silver pellets and iron slags. Best way to put down one of these haints. I fish a sidewinder pocket watch from my knickers, glancing at the open-face front.

“You and Sadie bring the truck.” I nod at the Ku Kluxes. “I’ll get them ready for hauling. Hurry now. We ain’t got much time.”

“Why I got to go get the truck?” Sadie whines.

“Because we need to get a yella gal with a big ol’ gun off the streets,” Chef retorts, throwing a rope over the warehouse edge.

I don’t wait to argue Sadie’s complaints; she got lots of those. Grabbing hold of the rope, I start making my way down. Tried our best to mask what we been doing. But anybody come looking and find three dead Ku Kluxes and three colored women—well, that’s for sure trouble.

I’m about halfway to the ground when Sadie calls out, “I think they moving.”

“What?” Chef asks, just above me. “Get on down the rope, gal, and let’s go—”

Sadie again: “I’m telling y’all, them Ku Kluxes is moving!”

What she going on about now? I twist about on the rope, holding to the thick cord with my legs locked onto the bottom. My heart catches. The Ku Kluxes are moving! The big one sitting up, feeling at his caved-in chest. The portly one’s stirring too, looking to his missing arm. But it’s the lanky one that jumps up first,face half gone so that you can see bone showing. His good eye rolls around till it lands on me and he opens his mouth to let out a screech that ain’t no ways human. That’s when I know, things about to get bad.

The sickening sound of bone cracking, of muscle and flesh stretching and pulling, fills the alley. The lanky man’s body grows impossibly large, tearing out his skin as easy as it shreds away his white robes. The thing standing in his place now can’t rightly be called a man. It’s easily nine feet tall, with legs that bend back like the hindquarters of a beast, joined to a long torso twice as wide as most men. Arms of thick bone and muscle jut from its shoulders, stretching to the ground and ending in claws longer than Chef’s knife. But it’s the head that stands out—long and curved to end in a sharp bony point.

This is a Ku Klux. A real Ku Klux. Every bit of the thing is a pale bone white, down to claws like carved blades of ivory. The only part not white are the eyes. Should be six in all: beads of red on black in rows of threes on either side of that curving head. But just like the lanky man, half its face been ripped away by Chef’s bomb. The eyes that’s left are all locked on me now, though. And what passes for lips on a long muzzle peel back, revealing a nest of teeth like spiky icicles—before it lunges.

Watching a Ku Klux raging at me while dangling off the side of a building is one sight I could do with forgetting. There’s the crack of a rifle and a bullet takes it in the shoulder. Another crack and a second bullet punches its chest. I glance up to find Sadie, looking like a photo I once seen of Stagecoach Mary, shells flying as she works the lever. She hits the Ku Klux two more times before stopping to reload. That don’t kill it, though—just sends it reeling back, bleeding, in pain, and mad as hell.

Still, Sadie’s bought me precious seconds. Above, Chef is calling with an arm extended. But I won’t make that climb—not before the Ku Klux is on me. Searching frantic for a way out, my eyes land on a window. I slide down the rope, palms burning on the coarse fibers. Please let it be open! Not open, but I almost shout, “Hallelujah!” when I see it’s missing glass on one side. I grab the upper edge with a hand while planting a brown Oxford on the bottom. Above I hear shouts,and from the corner of my eye catch the Ku Klux running for me and leaping, claws extended and mouth wide.

I push through that open slot and practically fall inside, just before the Ku Klux hits the wall. A long snout breaks through the remaining glass, snapping at air. Sadie’s rifle goes off again, and the monster roars in pain. Turning its gaze up, it digs bony claws into the brick and starts to climb.

I watch all this lying on a bale of cotton. Lucky, because I’d be a sight more tore up landing on the wood floor. Still, that fall hurt something awful. It take a moment to roll off my back and stumble to my feet, feeling bruised all over. Except for sunlight streaking through windows,it’s dark in here. Stifling hot too. I shake my head to clear it. Don’t hear no more rifle shots, but I know there must be a fight on the roof. Need to get back up there to help Chef and Sadie. Need to—

Something heavy rams the warehouse doors,making me jump. Did somebody finally hear all the noise we making behind the fireworks and whatnot and come looking? But when the doors get hit again, strong enough to almost buckle them, I know that’s not people. Only thing big enough to do that is—the doors are ripped near off their hinges before I can finish the thought, spilling in daylight and monsters. The two other Ku Kluxes. My luck done run out.

They easy enough to recognize. One missing an arm. The other, possibly the biggest Ku Klux I ever seen, got a dent in its pale white chest. The two sniff at the air, searching. Ku Kluxes don’t have good eyesight, even though they got six. But they can smell better than the best hound. It take two heartbeats for them fix on me. Then they’re galloping on all fours, snarling and marking me as prey.

But like I said already, I hunt monsters.

And I got a sword that sings.

It comes to me at a thought and a half-whispered prayer, pulled from nothingness into my waiting grip—a silver hilt

joined to smoke that moves like black oil before dripping away. The flat, leaf-shaped blade it leaves behind is almost half my height, with designs cut into the dark iron. Visions dance in my head as they always do when the sword comes: a man pounding out silver with raw, cut-up feet in a mine in Peru; a woman screaming and pushing out birth blood in the bowels of a slave ship; a boy, wading to his chest in a rice field in the Carolinas.

And then there’s the girl. Always her. Sitting in a dark place, shaking all over, wide eyes staring up at me with fright. That fear is powerful strong—like a black lake threatening to anoint me in a terrible baptism.

Go away! I whisper. And she do.

Except for the girl, the visions always different. People dead now for Lord knows how long. Their spirits are drawn to the sword, and I can hear them chanting—different tongues mixing into a harmony that washes over me, settling onto my skin. It’s them that compel the ones bound to the blade—the chiefs and kings who sold them away—to call on old African gods to rise up, and dance in time to the song.

All this happens in a few blinks. My sword is up and gripped two-fisted to meet the Ku Kluxes bearing down on me. Big as it is, the blade is always the same easy balanced weight—like it was made just for me. In a sudden burst the black iron explodes with light like one of them African gods cracked open a brilliant eye.

The first Ku Klux is blinded by the glare. It stops short, reaching its remaining arm to put out the small star. I dance back, moving to chants thrumming in my head, their rhythm my guide, and swing. The blade cuts flesh and bone like tough meat. The Ku Klux shrieks at losing a second arm. I follow through with a slash at its exposed neck, and monster crashes down, gurgling on dark spurting blood. The bigger Ku Klux lumbers right atop it to reach me and there’s a dull crack I think is the wounded monster’s spine.

One down.

But that big Ku Klux not giving me time to rest. It launches at me, and I jump out the way before I get crushed. I give a good biting slash as I do and it howls, but lunges again, snapping jaws almost catching my arm. I duck, moving deeper into the maze of bundled cotton, zigzagging before squeezing into a space and going still.

I can hear the Ku Klux, raking claws through cotton bales, searching for me. My sword has thankfully gone dark. But I won’t stay hidden long. I have to become the hunter again. End this.

C’mon, Bruh Rabbit, my brother urges. Think up a trick to fool ol’ Bruh Bear!

Pulling out my pocket watch, I kiss it once. Quick as I can, I rise up and hurl it clattering across the wood floor. The Ku Klux whips about, tearing after the noise. As it does I climb onto the bales, running and hopping from one to the other, until I get to where it’s hunched over, sniffing the pocket watch—before smashing it under a clawed foot.

That makes me madder than all else.

With a cry I hurl myself at it, the chants in my head rising to a fever pitch.

I land on the monster’s back, the blade sinking through flesh into the base of its neck. Before it can throw me off I clutch at ridges on its pointed head and with my whole body push the blade up and deep. The Ku Klux jerks once before collapsing facedown, like its bones turned to jelly. I fall with it, careful not to get rolled under, still gripping the silver hilt of my sword. Regaining my breath, I do a quick check to make sure nothing’s broken. Then pushing to my feet, I press a boot onto the dead thing’s back and pull the blade free. Dark blood sizzles off the black iron like water on a hot skillet.

Catching movement out the corner of my eye I spin about. But it’s Chef and Sadie. Relief forces my muscles to relax and the chanting in my head lowers to a murmur. Chef lets out a low whistle seeing the two dead Ku Kluxes. Sadie just grunts—closest she comes to a compliment. I must look a sight. Somewhere along the way I lost my cap, and my undone hair is framing my coffee-brown face in a tangled black cloud.

“Called up your little pig sticker?” Sadie asks, eyeing my sword.

“The one up top?” I ask, ignoring her and breathing hard.

Sadie pats Winnie in answer. “Took a mess of bullets too.”

“And this knife when things got close,” Chef adds, patting her war souvenir.

Outside the parade’s moved on. But I can still hear the brass band and fireworks. As if a whole lot of monster battling ain’t happened just some streets over. Still, somebody over there bound to know the difference between firecrackers and a rifle.

“We need to get moving,” I say. “Last thing we need is police.”

Macon’s constables and the Klan not on good terms. Surprising, ain’t it? Seems the police don’t take well to them threatening to run one of their own for sheriff. That don’t mean the police friendly with colored folk, though. So we try not to cross them.

When Bruh Bear and Bruh Lion get to fighting, I remember my brother saying, Bruh Rabbit best steer clear!

Chef nods. “C’mon, yella gal—say, what you doing there?”

I turn to find Sadie poking at a cotton bale with her rifle.

“Y’all ain’t ever worked a field,” she’s muttering, “so don’t expect you to know better. But July is when the harvest just starting. Warehouse like this should be empty.”

“So?”I glance nervous at the alley. Don’t got time for this.

“So,” she throws back at me, reaching inside a bale. “I want to see what they hiding.” Her arm comes back out, holding a dark glass bottle. Grinning, she pulls out the cork and takes a swig that sets her shivering.

“Tennessee whiskey!” she hoots.

Chef dives for another bale, digging with her knife to pull out two more bottles.

I give Sadie my own grunt. Tennessee whiskey worth a pretty penny, what with the Prohibition still on. And this

little monster-hunting operation costs money.

“We’ll take what we can, but we need to hurry!”

I look down at the dead Ku Klux. The monster’s bone-white skin is already turned gray, scraps peeling and floating into the air like ashes of paper, turning to dust before our eyes. That’s what happens to a Ku Klux when its killed. Body just crumbles away, as if it don’t belong here—which I assure you it does not. In about twenty minutes won’t be no blood or bones or nothing—just dust. Make it feel like you fighting shadows.

“You need help with—?” Chef gestures at the dead Ku Klux.

I shake my head, hefting my sword. “Y’all bring the truck. Nana Jean been expecting us. I got this.”

Sadie huffs. “All that fuss over a dog, and this don’t make you blink.”

I watch them go before fixing my eyes back to the dead Ku Klux. Sadie should know better. That dog didn’t hurt nobody. These haints evil and need putting down. I ain’t got a bit of compunction about that. Lifting my sword, I bring it down with a firm swing, severing the Ku Klux’s forearm at the elbow. Blood and gore splatters me, turning at once to motes of dust. In my head the chanting of long-dead slaves and bound-up chiefs starts up again. I find myself humming along, lost to the rhythm of my singing blade, as I set about my grisly work.

Excerpted fro Ring Shout, copyright © 2020 by P. Djèlí Clark