Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches.

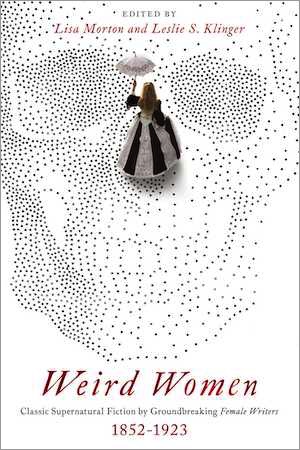

This week, we’re reading Louisa May Alcott’s “Lost in a Pyramid, or the Mummy’s Curse,” first published in Frank Leslie’s 1869 A New World. (We read it in Lisa Morton and Leslie S. Klinger’s new Weird Women: Classic Supernatural Fiction by Groundbreaking Female Writers 1852-1923.) Spoilers ahead.

“You’ll be sorry for it, and so shall I, perhaps; I warn you beforehand, that harm is foretold to the possessor of those mysterious seeds.”

Evelyn models for her cousin and fiance Paul Forsyth’s painting. She amuses herself with trinkets they’ve rummaged from an old cabinet, including a tarnished box holding three scarlet seeds. When she asks Forsyth about them, a shadow crosses his face. There’s a weird story behind them, one that will haunt her if he tells it.

Oh, but she likes weird tales, and they never trouble her. Evelyn wheedles this history from Forsyth:

During his Egyptian travels, Forsyth and Professor Niles explore the Pyramid of Cheops. Accompanied by Forsyth’s guide Jumal, they thread narrow passages and stumble over mummy-cases—and mummies. Forsyth wearies, but the indefatigable Niles wants to stay. They compromises, resting while Jumal finds Niles another guide. While Forsyth naps, Niles takes a torch to adventure alone! Forsyth follows Niles’ guideline, but Niles has rashly continued after the line plays out. Forsyth leaves his torch as a marker and tracks Niles by his faint shouts. Unfortunately they’re now lost in a labyrinth, their single torch waning, and Niles falls and breaks his leg!

Despite his pain, Niles comes up with a plan. If they start a fire, the smoke may lead Jumal to them. Luckily a wooden sarcophagus rests in a nearby niche. Forsyth grapples it down, spilling out a mummy. He nervously moves the “little brown chrysalis” and ignites the sarcophagus. While they wait, Niles—ever the scientist—unwraps the mummy. A woman’s body emerges along with aromatic gums and spices—and shriveled hands clasping the very seed-box Evelyn holds!

As their fire gutters, they hear Jumal’s far-off voice. Their only remaining fuel is the mummy herself. Forsyth hesitates over this final desecration, but what choice does he have? He consigns the pitiful relic to the fire. Dizzy with its suffocating smoke, he passes out. Next he knows, Jumal’s rescued them.

Evelyn puts aside the gold box, but presses for more detail. Forsyth admits that the tomb-spoils included a parchment declaring the mummy a sorceress who cursed anyone disturbing her rest. Nonsense, yet Niles has never quite recovered, and Forsyth’s dreams remain haunted.

Never gloomy, Evelyn’s soon cajoling Forsyth to give her the seeds to plant. He refuses, fearing they harbor some evil power. He flings them into the fire, or thinks he does. Later, though, he finds one on the carpet. Curiosity aroused, he sends the seed to Niles. Niles reports that it grows marvelously; if it blooms in time, he’ll take it to a scientific meeting for identification.

On their wedding day, Forsyth tells Evelyn about Niles’ success. In recent months she’s suffered from fatigue, fever and chills, and cloudiness of mind, but his news enlivens her. She confesses she too found a seed, and planted it, and her plant has already bloomed! It has vivid green leaves on purple stems, rankly luxuriant. Its single ghostly white flower, spotted in scarlet, resembles the head of a hooded snake. She means to wear the flower as a wedding ornament. Forsyth protests, suggesting she wait until Niles identifies it.

Evening finds Evelyn revived to her former vivacity and brilliance, and more. Forsyth’s startled by his bride’s almost unearthly beauty and the strange fire in her eyes. As festivities wind down, her color fades, but her weariness is surely understandable. She retires. A servant hands Forsyth an urgent missive.

It brings news of Niles’ death and his last words: “Tell Paul Forsyth to beware of the Mummy’s Curse, for this fatal flower has killed me.” He wore the thing to his meeting, where participants watched its dewy drops slowly turn blood-crimson. Niles started the evening unusually animated, then suddenly dropped as if in apoplexy. After death, scarlet spots like the flower’s appeared on his skin.

An authority pronounced the plant one of the deadliest poisons known to Egyptian sorcery. The plant itself gradually absorbs its cultivator’s vitality; wearing the blossom produces either madness or death.

Forsyth rushes to his bride, who lies motionless on a couch. On her breast is the snake’s-head blossom, white petals crimson-flecked. Only faint breath and fluttering pulse show Evelyn lives.

The mummy’s curse has come to pass! Death in life is Evelyn’s doom, while Forsyth’s is to tend her through the years with a devotion its ghost-like recipient can never thank by word or look.

What’s Cyclopean: Forsyth is exceedingly Victorian: “That is a weird story, which will only haunt you if I tell it.” “I warn you beforehand, that harm is foretold to the possessor of those mysterious seeds.” If you can’t be smart and genre-savvy, you can at least be ominous.

The Degenerate Dutch: Victorian Brits steal “antiquities” from Egyptian pyramids and feel vaguely guilty about it; somehow this doesn’t work out for them.

Weirdbuilding: Morton and Klinger list this as the first “major work” of horror to incorporate a mummy.

Libronomicon: Notes and scraps of parchment make up our reading material this week: Niles’ ill-omened claim to have “a clue,” and the sorceress’s promise to curse anyone who disturbs her body. (It’s an extremely practical curse, really—shades of Agnes Nutter.)

Madness Takes Its Toll: The sorceress’s plant appears to be a slow-acting neurotoxin—ultimately producing “either madness or death.”

Anne’s Commentary

Perhaps the only people surprised to learn that Louisa May Alcott would write something like “Lost in a Pyramid” would be those who’ve never read Little Women. [RE: Guilty.] Jo March first earns serious money as a writer after attending a public lecture on, of all things, ancient Egypt. While waiting for it to commence, she amuses herself with a newspaper fiction illustrated by “an Indian in full war costume tumbling over a precipice with a wolf at his throat, while two infuriated young gentlemen […] were stabbing each other close by, and a disheveled female was flying away in the background.” The paper offers a hundred dollar prize for similar “sensation” stories, and Jo resolves to attempt one. She wins the prize and follows up with “The Duke’s Daughter,” “A Phantom Hand,” and “The Curse of the Coventrys,” all of which “proved the blessing of the Marches in the way of groceries and gowns.”

Inspired by the much-needed income, Jo pumps out ever more lurid tales, for “in those dark ages, even all-perfect America read rubbish.” Then friend (and later husband) Professor Bhaer morally mortifies her by sniffing that sensational writers “haf no right to put poison in the sugarplum, and let the small ones eat it.” Jo burns her trashy stories and writes no more; at least she has the Yankee sense to keep the money.

Alcott, the real-life Jo, wrote many sensation pieces under the pen name A. M. Barnard. These include such ripping titles as A Long Fatal Love Chase and Pauline’s Passion and Punishment. Unlike Jo, I guess, she was never so much in love with a man as to regret writing them.

The only mummy story I recall in which things turn out all right is one we read a while back, Theophile Gautier’s “The Mummy’s Foot.” Someone wicked has stolen Princess Hermonthis’s pretty little mummified foot, but when its latest owner returns it, she’s all forgiveness and (after a whirlwind tour of the Egyptian underworld) leaves him a green paste idol in its place. Alcott’s “Lost in a Pyramid” falls closer to Lovecraft’s “Under the Pyramids” on the whimsy-to-terror continuum; it surpasses the Lovecraft-Houdini collaboration in poignancy. The fictional Houdini faces subterranean trials more harrowing than Paul Forsyth’s, horrors far more ghoulishly varied and vital, but Houdini emerges essentially unscathed—an outcome Lovecraft rarely granted his “own” characters. Forsyth will ultimately lose everything. So will Evelyn. Forsyth at least semi-deserves his fate, Evelyn not at all.

Evelyn wasn’t the one to doubly desecrate the sorceress’s mummy. Forsyth didn’t share Niles’ callousness; he felt there was “something sacred in the bones of this unknown woman,” yet he put his qualms aside to unwrap her remains, then immolate them. He admits he’s never quite forgiven himself for stealing the mummy’s box—stealing is his word. A few pages later, he affects breeziness: “Oh, I brought it away as a souvenir, and Niles kept the other trinkets.”

Forsyth flip-flops more than an overcaffeinated sidewinder. He hesitates to tell Evelyn his tale, then lets her sweet-talk it out of him. Maybe he hoped she’d do so—why else tease her curiosity with the gold box? Does Forsyth do this of his own accord, or does the mummy’s curse subtly compel him, thus drawing innocent Evelyn into its coils?

Must the curse, if real, be inevitable, leaving Forsyth and Niles—and Evelyn—screwed from the start? If not, what could have defeated it? Counter-magic comes to mind, but that solution requires the often agonizing acceptance that magic (or super-science, etc.) exists. See Dr. Armitage using the Necronomicon to dispel the more monstrous Whateley twin, or Dr. Willett employing Curwen’s “resurrection” counterspell to put the wizard down. At least provisionally accepting the notion of supernatural retribution could’ve kept Forsyth from one minute fretting about a curse and the next laughing it off and doing precisely what promoted its consummation. He has a baaad feeling about relating the story, but he does it anyhow. He says Niles has never been right since the mummy incident, kinda like he’s cursed, but no, not really. He senses evil potential in the seeds—and for once does the right thing by incinerating them.

Almost incinerating them. Seeing one seed has survived, does he quickly chuck it into the flames? No. Instead, he sends it to the one other person who absolutely shouldn’t have it, fellow cursee Niles. He blames Evelyn’s curiosity for rousing his own. Key difference: Evelyn’s curiosity is rational, for she dismisses the idea of a curse.

Forsyth’s final perversity is dismissing Evelyn’s wasting illness as the natural consequence of planning a wedding. Her almost unearthly revival during the festivities unnerves him, but chalk that up to natural excitement. The subsequent crash, again, natural exhaustion.

If only Niles could have delivered his dying warning earlier!

Now, that splendid deadly plant! It’s only fitting an Egyptian sorceress should favor a plant resembling a cobra. Jo March, in her sensational phase, troubles librarians with requests for books on poisons. I wonder what research Alcott did on her fatal flower. Curiously, there’s a plant that broadly resembles the one she describes: Darlingtonia californica, the California pitcher plant or cobra lily. It’s even carnivorous, a waster of flesh like the sorceress’s pet! Its “cobra-heads” are tubular translucent leaves trailing tongue-like leaflets, but they do look like flowers, and they do sport dewy speckles. The plant was discovered in 1841—could Alcott have been aware of it?

Because the cobra lily grows only in cold-water bogs in California and Oregon, our sorceress wouldn’t have encountered it among the papyrus stands of the Nile. On the other hand, being a particularly famous sorceress, perhaps she had means for traveling far afield. Egypt to California could be but a day-trip on Sphinx-back, after all.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

There’s something very Victorian about mummy curses. There’s a reason for that: it was the era when the British moved from looting tombs as a sideline to military invasion to looting tombs as a form of mass entertainment, and they kinda knew it was a dick move. I won’t dwell on this at great length, lest I devolve into the equivalent of a review of Moby Dick reading SAVE THE WHALES. (Actually, that could work, given that the novel treats whales as less a game animal, and more the opposite side of a long and approximately-evenly-matched war, who are also sometimes God, but I digress.) However, let it stand as read that a certain percentage of western horror translates to “What if someone punished us for being imperialist douchebags? Better feel vaguely guilty but also relieved that it’s merely fantasy.”

Tomb-raiding and grave-robbing have a long and ignoble history, and tend to make people feel uncomfortable even when they’re also excited about the treasures to be found in said graves. In real life, even domestic grave-robbing has relatively mundane consequences. In stories, on the other hand, you might be hounded by a dead sorcerer, cornered in a coffin by a giant rat, or gothily seduced and drained of your life force. (If you are yourself a sorcerer—or a worm with ambitions of sorcery—things are likely to work out considerably better. The dark arts have their advantages, and only sporadically result in just desserts.)

We’ve touched on pyramidal horror a couple of times in this column, though in neither case was a traditional curse at work. Gautier’s “The Mummy’s Foot” sidesteps any sort of vengeance by making the protagonist only an accidental foot-thief, entirely willing to return the appendage to its original princess. Lovecraft’s collaboration with Houdini, on the other hand, is less interested in anything humanoid and more in giant sphinx-monsters. Alcott’s title suggested something more standard—the most predictable sort of mummy’s curse involves the grave-owner taking directly personal umbrage, so I was somewhat nonplussed when her tale contained exactly zero animate mummies. To make up for it, we have an ancient sorceress and a pair of hobby archaeologists who rate maybe a 2 on the Indiana Jones tomb robbing scale. (Where 10 involves regular successful escapes from technically-sophisticated booby traps, and 1 involves not surviving your tendency to wander off unescorted into labyrinths.)

Even better, the sorceress clutches viable ancient seeds for a plant that would send Beatrice Rappaccini into raptures. (I assume that either she or her dad is the “best authority” who instantly IDs the thing.) Poison is inherently cosmic horrorish, yes? It may be an invisible miasma or a flower so beautiful you can’t resist touching it, a pinprick or a dress or an almond-flavored delicacy. The means by which it kills may seem inexplicable, especially sans modern medicine and chemistry. Even then, there’s something mystically disturbing about it, especially as we come to realize how many substances and energies are fundamentally incompatible with human life and health.

The seeds’ danger is particularly cryptic for Evelyn and Forsyth and Niles. You kind hope that if you started growing a mysterious ancient plant and instantly sickened, you might think about allergy tests—but for the Victorians, this is barely science fiction, let alone fantasy. They surrounded themselves with wallpaper, clothing dyes, and air that could at any point lead to dramatic and mysterious declines and/or deaths. (Unlike us modern folk, of course, who totally avoid exposure to new and half-understood toxic substances.) Given the long popularity of arsenic wallpaper, I can only assume that Cursed Mummy Flowers are going to be the next big thing.

Final note/fascinating research rabbit hole: reports of viable “mummy wheat” required regular debunking from the mid-1800s through the mid-1900s. Older seeds have in fact germinated, but not from that source. And not, so far, hideously neurotoxic.

Next week, we continue with The Haunting of Hill House, sections 3-5 of Chapter 1, in which we journey on toward the House.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her short story collection, Imperfect Commentaries, is now available from Lethe Press. You can find some of her fiction, weird and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.