It’s The Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown first aired on October 27th, 1966, meeting CBS’s demand for another Peanuts holiday-themed special that could run annually, like the previous year’s A Charlie Brown Christmas. CBS reportedly went so far as to say that if Charles Schulz and Bill Melendez couldn’t deliver a hit, they wouldn’t order any future Peanuts specials. Luckily The Great Pumpkin was a success, and even added a new holiday figure to the American pantheon, as many people assumed the Great Pumpkin must be a real folk tradition.

I revisited the special recently, and found a much weirder, darker world than I remembered…

Allow me to be briefly autobiographical: I spent a large portion of my life in Florida. Now while I’ll grudgingly admit that Florida has some good aspects, as a pale goth-ish person who hated being in direct sunlight, didn’t like the beach, and never developed a taste for meth, there wasn’t much there for me. Worst of all, since I’d spent the first few years of my childhood in Pennsylvania, I missed seasons. I liked the way the year turned, the way weather followed a predictable cycle that tied you to life in a visceral, subconscious way. Because of this I attached an unhealthy importance to holiday specials. (That may be clear to anyone who’s read my exhaustive takes on Christmas specials each year.) But the two autumn-based Charlie Brown specials hold a special place for me, because what I missed most living in Florida was FALL. It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown gives us autumn leaves, enormous pumpkins, and sunsets so vibrant I’d just pause the tape and stare at the screen for a while, and the muted palette of the Thanksgiving special impressed me so much I think it’s part of why I love Wes Anderson.

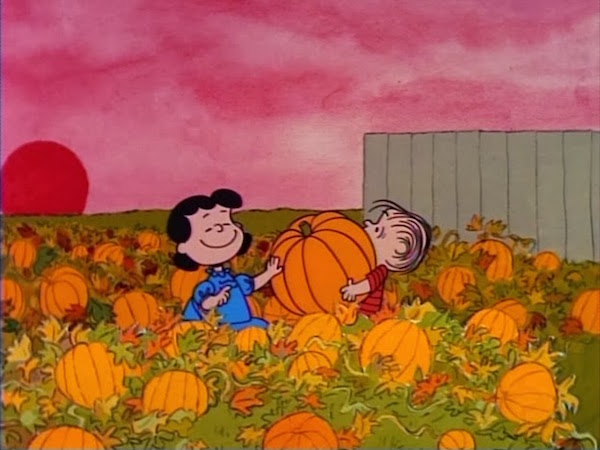

I mean, look at this at that glowing sun perfectly mirroring Linus’ pumpkin:

And look at that sky! And the variety of colors in the scattered leaves! And the soft, inviting glow of that light in the window!

Great Pumpkin gives you an autumn you can taste. But I didn’t really remember the story as much—I just remembered the visuals and the weird spooky mood. And when I went back and watched the special this week, I realized why. The special does a couple of interesting things with two of the lead female characters of the Peanuts universe, but overall I think I can say that this is the most depressing of all the Peanuts specials. (Just kidding. It’s this one.)

So let’s look at the highlights and weirdness of this classic.

Sally Brown: Unlikely Feminist Icon

Sally is excited to take an important step into adulthood by participating in tricks or treats, but she has some moral checkpoints to consider—she doesn’t want to do anything illegal, and she doesn’t want to take part in a rumble. We see right away that she’s an independent young woman—after all, she successfully makes a ghost costume for herself when her big brother botches his. When Linus first weaves his tale of the great pumpkin, he expects her to buy it:

Linus: He’ll come here because I have the most sincere pumpkin patch and he respects sincerity.

Sally Brown: Do you really think he will come?

Linus: Tonight the Great Pumpkin will rise out of the pumpkin patch. He flies through the air and brings toys to all the children of the world.

But no.

Sally Brown: That’s a good story.

Linus: You don’t believe the story of the Great Pumpkin? I thought little girls always believed everything that was told to them. I thought little girls were innocent and trusting.

Sally Brown: Welcome to the 20th century!

I think Sally has a bright future ahead of her. She loves her Sweet Babboo, yes, but she’s still her own person. She chooses her iconoclastic love over the pack mentality of the other children, but it’s her choice. Linus doesn’t pressure her. (He proselytizes a little, but that’s kind of his jam.) And when Sally realizes that she’s been screwed out of candy, she doesn’t just mope like her brother does: she demands restitution.

What’s the Deal with the World War I Flying Ace?

Snoopy is the Peanuts universe’s escape valve. He’s weird, adventurous, whimsical, and doesn’t care what the children think of him. He walks freely into peoples’ homes, and has both his own rich inner life, and his own home, which seems to be TARDIS-like in interior space. He is their Tigger, their Toad, their Huck Finn. In this special, far from the fun romp of winning a Christmas decoration contest, Snoopy imagines himself as the Great World War I Flying Ace. Fine. But rather than having a grand adventure, he is almost immediately shot down by his nemesis the Red Baron.

On the one hand this is great—it taps into the power of a kid’s imagination, the animation is gorgeous, and Guaraldi provides a score that, to this day, fills me with existential dread whenever I hear it.

But on the other hand… what the hell? What does this have to do with Halloween? Who thought children in 1966 were going to be invested in a weird subplot about a war that was fought two generations earlier? Who thought it was a good idea to send Snoopy the Dog through an absurdly realistic No-Mans-Land, crawling through barbed wire, fording a stream, and passing signs for real cities in France, all while fearfully looking around, waiting for enemy Germans to appear? Who decided to send him creeping through a shelled-out barn where, oh yeah, the walls are riddled with bulletholes?

What the hell, Charles Schulz? And even once he gets into the safety of Violet’s house, his costume inspires Schroeder to play World War I-era songs, which is fine until Snoopy begins sobbing during “Roses of Picardy” and finally leaves the party in tears.

Happy Halloween, everybody!

Umm… Rocks?

OK seriously why the hell are the adults in this town giving Charlie Brown rocks? Are they all participating in some weird adaptation of “The Lottery” that the kids don’t know about?

…shit, it’s that, isn’t it? Charlie Brown’s going to be murdered at the harvest festival.

And speaking of that…

The Unsettling Religious Implications of The Great Pumpkin

When A Charlie Brown Christmas aired in December ’65, it did two things that were unheard of on TV: it used actual children for voice actors, and it openly espoused a very particular religious viewpoint. This was just after the peak of 1950s Americana, the idea that Protestants, Catholics, and Jews could work together to form a bland coalition of faith and morality. While Charlie Brown embraced an avante garde jazz soundtrack courtesy of Vince Guaraldi, it did not embrace the Beats’ interest in Buddhism, and the wave of Eastern religions and New Age beliefs had not yet been popularized by the hippie movement. So for Linus to walk out and recite verse from Luke was shocking. This was no Ghost of Christmas Future here to make vague threats, or an angel either dashing (The Bishop’s Wife) or bumbling (It’s a Wonderful Life) come to earth to represent a benevolent but unnamed hierarchy: this was straight up Gospel, and the animators fought the network to keep it in the show. I hop holidays and mention this only to say that between this and Schulz’ public role as a Presbyterian youth pastor Methodist Sunday School teacher, the religious bent was firmly in the Peanuts universe.

What’s even more more interesting is the inversion happening here. If you’re a druid or a Wiccan, or just really really into being Irish-American (clears throat) you might claim the religious significance of Halloween, carve turnips, and celebrate this as a new year. Obviously if you celebrate Dia de los Muertos you commune with your loved ones, of if you’re Catholic you can observe All Saints and All Souls days with special services at church. However, U.S. Halloween, taken by itself, is an aggressively secular holiday, in which only candy and ironic “Sexy Fill-in-the-Blank” costumes are held sacred. But here’s our Matthew-quoting prophet professing his faith in a Great Pumpkin? An icon he just made up? What gives?

Charles Schulz answered this question in an interview in 1968: “Linus is a youngster to whom everything must have significance—nothing is unimportant,” Schulz told the Schenectady Gazette. “Christmas is a big holiday, and it has Santa Claus as one of its symbols. Halloween is also a special kind of day, so it ought to have some sort of a Santa Claus also. This is what bothered Linus.” Which makes sense to me—I remember being confused as a kid by the boundaries between holidays. Why did Christmas equal presents, but Easter and Halloween equaled candy? Why wasn’t there any gift-giving component to Thanksgiving? Why did New Years suck so much, and why did adults seem to like it? So making a central figure for Halloween (as Tim Burton and Henry Selick would do again a few decades later) works. What’s interesting is that Schulz creates an obvious allegory of religious faith, and unlike in A Charlie Brown Christmas, with its moments of blaring sincerity and the salvation of the tree, there is no reward for Linus’ faith. The Great Pumpkin, at its core, is a tale of disappointed religious faith. Linus receives no reward, no balm in Gilead, no candy in the Pumpkin Patch.

The show adheres closely to a classic Early Christian martyrdom narrative, except without the happy ending. When the other children mock and berate Linus for his belief in the Great Pumpkin, he remains calm. When Lucy threatens him with physical pain, he shrugs it off. He never threatens them with any sort of pumpkin spice wrath, hails of toasted, cinnamon-sprinkled seeds raining down upon his tormentors, scarecrows appearing at crossroads to castigate them for their lack of faith. He genuinely wants everyone to join in the bounty of toys. When even Sally abandons him, he calls after her, “If the Great Pumpkin comes, I’ll still put in a good word for you!” Linus is truly good.

But it’s here that the special turns.

Linus: “Good grief! I said “if”! I meant, “when” he comes! …I’m doomed. One little slip like that could cause the Great Pumpkin to pass you by. Oh, Great Pumpkin, where are you?”

Has there ever been a neater, more concise exploration of doubt? Within three sentences, Linus doubts the Great Pumpkin, berates himself for his lack of faith, and supplicates his orange deity for some special dispensation… and doesn’t get it. People may find it silly (it is a bit of fictional folk lore created for a cartoon special, after all), but I would hazard a guess that plenty of kids over the years have identified with Linus, and felt less alone because of this moment. And since, again, this special revolves around Linus’ own personally dreamed-up Pumpkin, there’s no reason for non-Christian kids to feel alienated the way they might be while watching A Charlie Brown Christmas. They can enter into this story, feel Linus’ doubt and guilt, and be just as disappointed as he is when the Great Pumpkin declines to appear.

Man Does This One Ever Stick the Landing

After all the melancholy, this special ends on an even more warm and humanistic note than the Christmas special. Lucy normally spends her time in both the comics and the cartoons being an utter jerk. Even in this one—she won’t let Charlie Brown kick the football, she tells him his invitation to Violet’s party is a mistake, she interrupts the other kids at the party to strong-arm them into bobbing for apples (and then claims the first turn, ugh) and, worst of all, is seriously cruel to Linus over his Great Pumpkin worship.

But as angry and annoying as Lucy is, she gets extra candy for Linus when she goes trick-or-treating, and since no parents seem to exist in this universe, we can assume that she did this on her own initiative. But best of all, she’s the one who realizes Linus never came home from the pumpkin patch. It’s Lucy who gets up at 4 in the morning, finds her brother, and leads him back home. She even takes his shoes off when she puts him to bed. It’s the perfect end to the special. The Great Pumpkin doesn’t come, Linus doesn’t get what he wants, but he does learn that his sister will be there even when deities fail.

And then he spends the credits ranting about how he still has faith in the Great Pumpkin because he’s Linus, and he’s got to believe in something.

This article was originally published in October 2016, for the 50th anniversary of It’s The Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown.

Leah Schnelbach is going to find a sincere pumpkin patch one of these days, they just know it. Come, sing “Roses of Picardy” with them on Twitter!