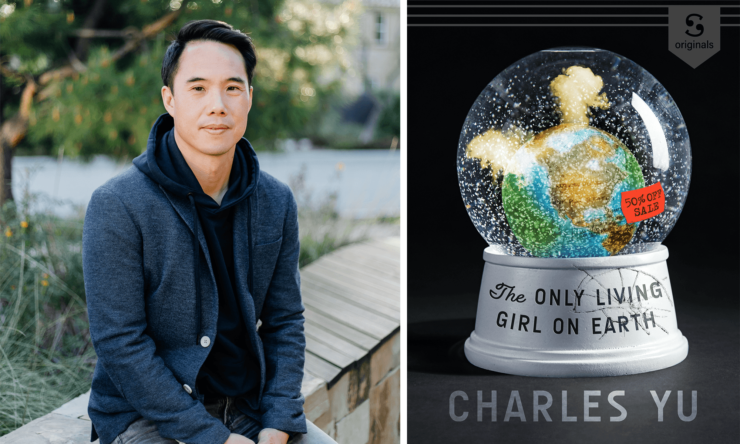

Charles Yu has been writing award-winning, genre-bending work for nearly twenty years now, including the short story collection Third Class Superhero and How to Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe, which was the runner-up for 2011’s Campbell Award for Best Science Fiction Novel. His work in television includes being a writer and story editor for the first season of Westworld, and his latest novel, Interior Chinatown, recently won the National Book Award in Fiction, a rare moment of joy in 2020.

Just before the new year, Yu and I spoke about the novel, writing techniques, and his new novelette, The Only Living Girl on Earth.

Interior Chinatown is an extraordinary work of metafiction: Chinatown is both a seedy, howlingly stereotypical set for a Law and Order-esque TV show called Black & White, and a real neighborhood, and a state of mind. Main character Willis Wu is an extra who wants to be promoted to the role of Kung Fu Guy, and he’s also a resident of Chinatown who wants to create a life for himself in the U.S. that doesn’t force him to be a cardboard cutout. But more than simply being a meta exercise, the book is hilarious and intensely moving. The same can be said of his literal rollercoaster of a sci-fi story, The Only Living Girl on Earth.

Set in 3020, the plot primarily focuses on a young woman named Jane who’s spending her last summer before college working in the Last Gift Shop on Earth—before an intense sojourn on America: The Ride. The story meditates on isolation, loneliness, and whether America—either as a concept, a country, or a theme park attraction—can possibly have a future. Yu was inspired by Ray Bradbury’s “There Will Come Soft Rains,” and began the story nearly a decade ago. The partnership with Scribd allowed him to revise just as the pandemic forced us all into lockdown. Without putting too much weight on that aspect, I will say that the story of a lonely woman working in near-total isolation has gained a peculiar resonance.

Our conversation opened with the uncanny robot voice of my recording app informing us that we were, in fact, being recorded. I apologized for the abruptness of the message, and Charles Yu responded that it was “surprising but not unwelcome—I like that it’s so upfront about its intentions.”

Always a reassuring quality in a robot! I started our (fully human) conversation by congratulating Yu on his NBA win for Interior Chinatown.

Charles Yu: It hasn’t quite sunk in! It doesn’t feel real, partly because this year doesn’t quite feel real. I haven’t seen anyone other than my family for… nine months? So, I don’t know—it’s just the latest in a string of surreal events.

I was really interested, when I read your new novelette, in seeing how you use the themes of isolation and tech run amok—I’m assuming that you had the story done before the pandemic set in?

CY: I’d been working on it with Scribd for the better part of the whole year, basically, and the story had been written prior to that. With Scribd it was more of a heavy revision.

I found it helpful to read. It made me feel a lot less paranoid, the story itself not only of Jane’s isolation, but then the whole idea of “America the Ride”—which has obviously somewhat broken down. It was nice to see how you expressed that in a way that in a way that a person can process. It’s not as huge as it feels as we’re all living through it, and being able to see it, as moving as the story is, it’s also…digestible.

CY: That’s what theme parks do, I think. It’s part of their function: to shrink the world down to a digestible scale. Years ago, I read Stephen Dixon’s story “Flying”—it has this incredible, thrilling sense of freedom, and also absolute terror. That story was still with me as I wrote “America the Ride”—the idea of a family moving through time, and in all of the scary parts of the ride, and exciting parts of the ride—feeling like you’re in the car together. Even in the process of writing, I had a feeling of “Oh, it’s gathering a little bit more momentum, here, and I might be able to get to some interesting places on this ride.”

Buy the Book

Interior Chinatown

I loved that element! I did see a throughline from that and Interior Chinatown, how you were using a meta element of people playing different roles, but also showing how they were moving through their lives through those roles. How the time collapses down at the end when Willis Wu is looking at his father with his daughter, and he’s seeing how all of their lives collapse into this one moment that he’s watching…I found it interesting the way that you were trying to mediate the passage of time, but through the idea of people playing different roles in a fictional television show—that’s also life—and then looking at the way you were doing that via a theme park ride.

CY: I’m always interested in finding a way, as you said, to collapse time, or to mix different tempos. To get the sweep of years or decades, the big picture, but then to bring everything down to a snapshot in your life. That’s how I experience things, maybe not in real-time, but how I remember them, how I re-create events in my life, this self-narration. Especially intense personal memories. This kind of combination of—it’s all a blur, and then there are these moments of intense clarity. And what’s also interesting to me is that these moments of clarity aren’t always big milestones. Often they’re low-key activities, watching TV with my kids or something, or driving to the grocery store with my wife. It’s so strange what ends up sticking.

We never what’s going to be important until after. Any time I’ve had an experience where in the midst of it I thought, “Oh this is something that’s going to stick with me forever” that isn’t usually the case. It’s usually the random moment that happened, like my friend said something that made me laugh harder than I had all week, or whatever, and that’s the thing…when I think of that person, that’s what comes up.

CY: Among the many things we have lost (and continue to lose) in this pandemic is what I would call everyday texture. In its place we have gotten a lot of strange, new experiences. I don’t pretend to have any special insight or perspective on what we’re going through, but obviously a lot of suffering and loss and isolation, but I do wonder what else might ending up staying with us. For me, it’s been this one-two combo of being together in our aloneness. It is weirdly a lot like the part in my story, of being on America: The Ride. We don’t know what’s coming next. We can see other people in their ride cars, and they’re on their track and we’re on ours. And we see other families, like “Hiii!” from a distance, or virtually, it’s just has intensified the feeling of being on a terrifying ride in the dark.

When you wrote Interior Chinatown, did it come to you as a hybrid of screenplay and novel? Or did it grow into that as you worked on it?

CY: It wasn’t until a couple of years into writing that the main character, Willis Wu, sprang into existence. I was very thankful he showed up, because when he did, things started to fall into place. However, his existence quickly led to many questions. For instance, if Willis is an actor, a background player, are we going to situate him in a show? If so, how do I represent that show? How self-aware is Willis about his role on that show? In terms of form, the question presented itself: “Could this been written as a screenplay?” What does that get me? What are the downsides, the constraints? That all happened very quickly after more than three years of trying to work on the book. Within a week or two, I had written fifty pages of this screenplay stuff. It was a mess and I knew eventually I’d have to sort it all out, but knowing I knew whatever else, I shouldn’t stop or even slow down, that I’d tapped into something interesting. Once the sentences started to flow I didn’t want to think too hard, and shut it off. The hybrid between novel and screenplay was super fun. It was the thing I’d been looking for all along, because it gave this opportunity to get into the consciousness of the character, and how he thinks, which is that he’s playing a role at all times also aware of playing that role, and yet not fully in control of when he’s following the rules versus not following the rules. That’s what I had fun with. Even visually, the experience of jumping back and forth between blocks of prose and a script format, that was liberating. Instead of looking at the page and saying. “OK, I’m thinking in my usual patterns how do I write this novelistically, I was just having a good time, surprising myself and discovering things. After three-and-a-half years of very much not having fun, to say “I’m just going to have fun. This doesn’t look at all like fiction—I don’t know what this is—but I’m just going to keep writing it.”

Do you have any books that are in your personal mental science fiction and fantasy canon, that you want to get more attention?

CY: I’m literally walking over to my bookshelf now! I love the works of Jeff and Ann VanderMeer as editors. I mean Jeff VanderMeer is obviously well-known for good reason, but for years I’ve been fans of their work as editors. From time to time they invite me to contribute to anthologies, and I’ve gotten to know them a bit as editors. They have one, The Thackery T. Lambshead Cabinet of Curiosities, which is the weirdest book ever. It’s fantastic.

I’m kind of obsessed with the idea of canon creation, and who gets in and who doesn’t. Whenever I talk with a writer, I want to know what pops into their head for a canon.

CY: Another editor is John Joseph Adams: when I read one of his anthologies, I see names I recognize and names I don’t, but then over time, the latter group starts shifting into the former—the process of John or Jeff and Ann discovering new voices, publishing them, amplifying them, it’s very cool to watch from afar. This role, this ability they have to be so discerning and yet, open…those seem to be contradictory, and yet they’re able to spot new people and new writing before others do. Oh, and Dexter Palmer’s book Version Control! It’s incredible. He’s a really brilliant person and writer, and in the sea of books, people should study it.

I read an interview where you pinpointed, as the thing that made you want to write, “The Most Photographed Barn in America” section in Don DeLillo’s White Noise. I wanted to know if there was a book that that turned you into a reader as a child, and then, if there was a book as an adult that made you think “Oh, I could actually do this,” like that you were able to take the book apart, and see how to put a book together.

CY: That would be a cool idea for an anthology! What was the book that made you think, “Oh I could actually do this.” Because, and I think this is true for me but I’d wager I’m not alone, it’s not always the books you love the most. What I mean is, there are those books that make you say “I love that book, but I don’t know how it was made. I can’t see any of the seams.” And then there’s others where maybe you don’t love the book as much, but something about its construction allows you a glimpse into how it would be possible to construct such a thing yourself.

I remember reading Piers Anthony’s Incarnations of Immortality. The first book in the series was On a Pale Horse, and–this is a minor spoiler, but it’s a 35-year-old book – it’s about a guy who accidentally kills Death, so he has to become Death. And he’s doing the job…now I’m giving away my bag of tricks…he has no idea how to do his job. And it was, “Oh, this is really interesting. Being Death is a job, and this guy is new at it.” It was such a cool way to enter that idea. His jurisdiction is only when someone is very closely balance between having been god and evil in their lifetimes. If it’s clear where they’re supposed to go, Good Place or Bad Place, the soul just goes there. Death only shows up for the really hard cases. Anyway, I was hooked, and proceeded to plow through the rest of the series. Seven books, each one is an abstraction: Time, War, Nature, and then six and seven are the Devil, and God? I didn’t start writing fiction at that point – but the premise, the structure of the series, that stayed with me.

When I actually did start trying to write fiction, the book that did this for me was Self-Help by Lorrie Moore. The immediacy of her voice. How she gets to the heart of things. I didn’t have any formal education in fiction writing, I didn’t get an MFA, so reading that collection was instructive and inspiring in many ways.

I know a lot of people have been having trouble reading, but have you read anything in the past year that you loved?

CY: I really loved A Children’s Bible, by Lydia Millet. It’s an end of the world story, and it was an intense read this year.

I think most writers have an obsession or a question that they keep returning to in their work, and I was wondering if you feel like you have one, and if you do have on, what it is?

CY: It’s probably some version of what we were talking about earlier, “How do I convincingly fool people into thinking I’m a real human?” I think on some level I’m always writing about people playing a role, or pretending, because they don’t feel like they know how to inhabit the body that they’re given. “What am I doing here? How did I get here? Now what am I supposed to do?” I think that’s constantly having people wake up bewildered “How do I not get caught impersonating a human being?”

The Only Living Girl on Earth will be published on January 8, 2021, by Scribd Originals as an ebook and audiobook.