One book on my unread books shelf has been there for almost twenty years. It’s a copy of Jeffrey Eugenides’ Middlesex, a book I was once giddily excited about. When it was published, I was working for the kids’ division of his publisher, and though I had very little interaction with the folks on the adult-books side of things, I knew that if I could just summon up enough courage to go ask, I could maybe get an advance reader’s copy. I was shy and anxious, but I went upstairs, found his editor’s assistant, and asked, nervously, if I could possibly have a copy of the upcoming Eugenides.

I had never heard anyone say the name “Eugenides” out loud. “Oh,” said the assistant. His face was not kind. “Do you mean Jeffrey you-GEN-ih-dees?”

I got the book, but I was mortified. Eventually, I read part of Middlesex, then set it aside. A mystifying receipt for a six-pack, two bags of chips, and two bags of marshmallows marks my stopping place at page 79.

I can’t let that copy go. I may read it someday. Mostly it sits on the shelf and reminds me not to be a snob. In that way, it serves a purpose. But do the several hundred other unread books also serve a purpose?

If you want someone to tell you to hoard unread books, you can find a lot of people who will do just that. Many cite the essay in which Nassim Nicholas Taleb argues, “Read books are far less valuable than unread ones.” Taleb calls a collection of unread books an “antilibrary,” an awkward word with a lovely meaning: the books you haven’t read are a reminder of how much you have left to learn.

Other writers refer to tsundoku, “a Japanese word for a stack of books that you have purchased but not yet read,” according to The New York Times. It’s one of those words that feels like magic: having a term for the thing makes the thing feel more real, more legitimate. The sense that it’s a shared experience is stronger when there’s a word for it.

Last year, I bought more books than I’ve bought for a long time. Getting mail was one of 2020’s greatest small joys—getting book mail, doubly so. For years, I’ve worked in jobs that kept me in a steady stream of free or cheap books: publishing, arts editor at an alt-weekly, bookseller. This rich access to books is something I try very hard not to take for granted. When I was younger, I didn’t own extra unread books. I got stacks from the library, or I went to a bookstore and painstakingly picked out one book at a time. But eventually, through happenstance, choice, and privilege, the books began to pile up.

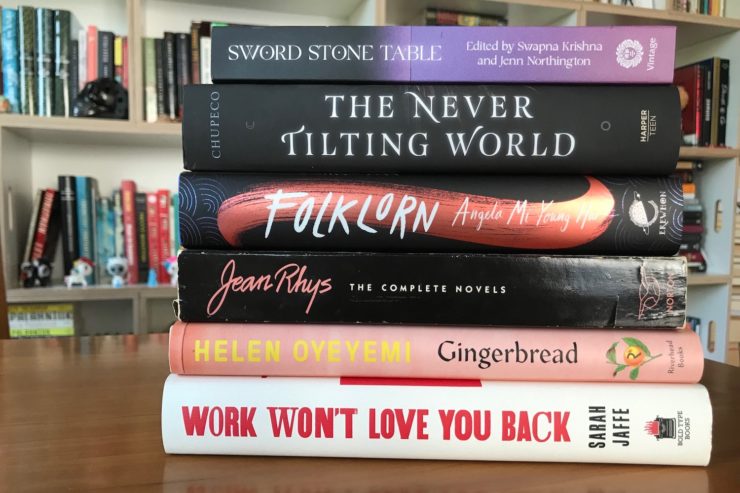

Unread books now exist in three states for me: Actual books, piled horizontally on a five-foot-wide bookcase; books listed in a tab on my reading spreadsheet, some sorted by category or interest; and the many books I’ve tagged “to-read” in my library app. There are probably some unread books on my iPad, too, but I try really, really hard not to buy ebooks I’m not going to read right away, as out of sight is out of mind and I will forget about them.

You could say books exist in two broad categories: read and unread. You could easily argue for a third: the semi-read books and the books that aren’t really meant to be read straight through (coffee-table books, reference books, art books).

But what about the books that slip through the fingers of a reader’s intentions?

In 2013, I read a Tumblr post that I’ve thought about regularly ever since. In it, author and PhD Jennifer Lynn Barnes addresses a phenomenon book-hoarders rarely mention: the way that a book can come to seem less appealing when it’s been sitting on your to-be-read shelf for a while:

Back in the 1950s, Leon Festinger proposed a concept called Cognitive Dissonance, which basically refers to a discomfiting state in which our actions and beliefs don’t line up. … One of the classic experiments of cognitive dissonance involves a choice task, where participants are asked to rate a bunch of “prizes” on how much they like them. Later, they are offered a choice between two prizes that they initially rated as equally appealing. Then, after participants finally make their choice, they’re asked to rate all of the prizes again. And basically what happens is that participants, on average, like the thing that they chose MORE than they did before they chose it, and they like the non-chosen item LESS. (This effect even persists with monkeys and children).

All of which is a very roundabout way of saying that a few years ago, I realized my To Be Read pile was recreating this experiment almost exactly. Every time I chose to read Book A and not Book B, Book B would become a little less appealing, even if I chose Book A because I was in the mood for that particular genre, or because a friend wanted to talk to me about it, or because Book B was longer and I didn’t have enough time to finish it, or because Book B was a hardback and wouldn’t fit in my purse, and NOT because I just wanted to read Book A more. But then, after not-choosing Book B, the next time I came back to my TBR pile, I would choose Book C over Book B, too… and so on and so forth until I didn’t really want to read Book B at all.

If you’re a person who just wants to have books, this may not bother you. Collecting books is a fine and noble pursuit, especially if you have the shelf/floor/nightstand space. But 90-95% of the books on my shelves are there because I genuinely want to read them. I ordered them or picked them out in a store or brought them home with enthusiasm and great intentions.

And then I didn’t read them. I picked other books instead—maybe the one I just got in the mail yesterday. Maybe a hold that came up at the library. Maybe a brand-new book I’m reviewing. Maybe that book I bought six years ago is one that I now think I can put in a nearby little free library—even though, when I bought it, I wanted to read it so much.

I can feel this happening when I look over at my TBR shelf. There are books from just months ago that I was so excited to get and yet I keep not picking up. There are books from years ago that I categorically refuse to part with, but am I going to read them? Would it be better to let them go now, and see if they come back into my life someday in the future, when I find a given book in a store and think Yes, now is the time!?

This doesn’t apply to special editions, or out of print books, the writing/craft/fairy-tale books that serve as my reference section and have a separate shelf. But sometimes I look at the TBR mountain and think, Do I want to climb you? Or was this a foolish dream in the first place?

The trippy thing is that this cognitive dissonance also happens with my lists. I’ve been trying, in the interest of space and saving money, to add books to my want-to-read lists rather than always buying them. (I still buy plenty.) But the more times I look at those lists and don’t pick those books, the more they fade from the forefront of my want-to-read brain. The titles become strings of words that don’t have the meaning, the promise, they once did.

There are very few unread books on my shelf that are as old as that copy of Middlesex. A huge hardcover history of Australia dates to 2006. Several small-press Catherynne Valente books are almost as old. (I read one of them this year, though! It does happen!) But my eye goes to the copy of The Only Good Indians that’s been calling to me for a year or so; am I too much of a horror wimp for it or not? Don’t I want to read Folklorn, with its shiny cover, which I just added to the stack a month or two ago?

I’ve considered declaring a form of TBR bankruptcy—giving away everything more than a year old, or picking some other arbitrary cutoff. Maybe I should arrange the books in order from those I’ve had the longest to those I’ve gotten most recently, and read in that chronology? Maybe I’ll get through them all if I try to alternate each newer book with an old-to-me book?

Like Barnes, I’ve also made smaller, secondary TBR piles—the “immediate TBR,” pictured above, which I fully intend to pull from after I finish what I’m reading. I did this, this week; after finishing David Mitchell’s Utopia Avenue for a book group, I reached for Shelley Parker-Chan’s She Who Became the Sun, which is now face-down on my coffee table, waiting to be picked back up.

The thing about the immediate-TBR, though, is that I keep it stacked with the spines away, so I don’t see them all the time. I know what’s there, but I like to imagine that not seeing them all the time short-circuits a teensy bit of the not-choosing effect. But we’ll see. Will I pick up Gingerbread or Work Won’t Love You Back next? Or will something else new and shiny have caught my eye by then?

The unread book shelf is comforting, in its way. I will never run out of books. Some of them, the ones I’ve been carrying around for years, feel like friends I just don’t know that well yet. We need to go on a friend-date, settle down for a long conversation, get to know each other better. But if I just keep adding more books, will the old ones ever have their day?

There aren’t rules for reading, of course. And some of those books are also there to remind me of something, like how Middlesex reminds me that snobbery accomplishes nothing. But the part of my brain that loves completing tasks and shelving books I’ve just read sometimes stares at the unread-books wall and wonders: What would it be like to catch up? To read them all? To clear the slate?

Molly Templeton lives and writes in Oregon, and spends as much time as possible in the woods.

Good essay; this nails the vague but genuine concept of a desire that doesn’t age as well as you’d expect. I’ve shifted entirely to e-books (the environment, cost, ease of transport), and – as the essay notes – it’s entirely too easy to let e-books slip away unread. (We need far better tools for e-book browsing, but that’s another matter). In part, the problem is exacerbated, in my case, by a) general library building (picking up piles of public domain classics) and b) library replication (buying e-copies of books I already own on paper). Managing the library on the e-reader – with its small screen and slow page turns – is effectively impossible, so I rely on Calibre, and a custom status field (unread, read, reviewed) to keep on top of what to read. Even that effectively focuses on obligations (NetGalley). There are just so many good books waiting that I choose among them partly at random. And of course, I mix in the occasional re-read, which slows things down more. I admit, though, that new-to-me physical books have a substantial edge in the TBR sweepstakes – they’re ever-present, constantly reminding me of their presence in a way e-books simply cannot.

Love this topic! I keep close track of my unread books for a lot of reasons that overlap with the ones in this article. Basically, I don’t yet know whether I like those books, and because I don’t yet know whether I like them, I don’t know whether they belong in my permanent collection. So they are monitored by a spreadsheet, which also keeps track of when and where I bought them and where they’re currently stored.

I have two rules. One, I have to be trying to get the number down in general. Buying books is acceptable, but there has to be a net decrease in the number over time. Two, the absolute cap is 300. I’m one of those people who moves often, and while I love actual physical books, they tend to be a bit heavier than ebooks. If I hit 300, moratorium on unread-book-buying until I get the numbers down. 300 is the point beyond which I presume it just spirals out of control for me.

The unread books I’ve had the longest – there are a handful from each of the years 2002 and 2004 – are definitely the ones most likely to feel like a bit of a burden by this point, and they’re also the ones that are the least likely to match my current reading interests. But my tastes haven’t shifted that much. I recently finished off the 2003 pile by reading Mona Clee’s clever Branch Point (1996) which is a hybrid Many-Worlds and alternative-history of the late 20th century, and loved it. I could tell when I found the used copy in 2003 that I was probably going to like reading it, and I was correct – regardless of the amount of intervening time. This means that just dumping the books from 15+ years ago might end with me skipping a few that I’d have liked, for no reason other than bad luck.

When I finish reading a book, I enjoy selecting a next one to read, but I never know how that decision is going to go until the last minute. This means that I can’t predict my recreational reading order with any accuracy. That doesn’t bother me, but it does mean I have to watch out for illusory convictions. In one case, I bought a book new in hardcover because I didn’t think I’d be able to wait for the paperback…and that was in 2006 and I still haven’t read it. Go figure. By this point, finishing an unread book is enough of a mini-accomplishment that I get a little shot of dopamine simply from deleting the entry from the spreadsheet. And another from either filing away the book (if it turns out I want to hang onto it) or going to deliver it to a Little Free Library (if not).

I totally agree about the value of keeping unread books out of sight. In my case, I’ve had it framed as more a positive than a negative cognitive bias, but I suspect it amounts to the same thing. The unread books I’ve stared at a gazillion times are familiar, but a little burst of novelty from finding something I hadn’t thought about in a while sometimes propels me through a book very readily, so maximising the novelty factor by deliberately not staring at the entire pile (or the entire spreadsheet) goes a long way.

A wonderful problem to have. My count of unread books in my possession is currently about 250, which is lower than it’s been in several years, and I’d like to knock it way down and train myself to use the library again once current conditions allow. Getting there. I do read quickly, but I have an intense day-job and an excessive number of other hobbies/pastimes, so there’s competition. Still. One at a time.

Well this describes my TBR pile pretty accurately! I usually refer to my older unread books as stale and the new ones as fresh, tender and delicious, or as having that new car smell, but now I have a more technical term for it! OTOH, during the pandemic I got through at least two-thirds of my unread stacks by either reading them or making the hard choice to donate them to a little free library. It felt pretty good, I gotta say.

I rarely turn down a deal on a book that I’m interested in, but the result is a TON of books that I have yet to get around to. After I read the article, I got curious, so I counted. Of 361 books on my shelves, 160 are unread. A hundred and sixty! I didn’t expect my TBR pile to be that high.

I, too, find that my interest in a book can wane with the passage of time. But I often have occasions when, searching for something to fit my mood, I choose such a book I’ve had on the shelves – sometimes for decades – and it it turns out to be exactly the right time and the perfect thing to read then. A very satisfying feeling (and it justifies the that long-ago purchase.)

I noticed this a few years back, and instituted a new rule for my TBR: Once I acquire a new book, I have until the end of the next calendar year to either read it or get rid of it. It’s actually helped make those older books more desirable again, and it’s forced me to cut down on the number of books I buy. But I found myself vaguely resentful when a friend signed me up for a monthly book subscription recently, because those books that I was only half-interested in were taking up valuable space on my shelf.

Wow, I feel totally seen right now. This is exactly what’s been happening with me. Some days I find those unread books a comfort and would never dream of parting with them before I’ve given them a chance. And some days I feel like they’re a bit of a weight on my shoulders, taking up space for the new books that I’m inevitably going to buy. It’s a constant dance, but honestly, I’m glad to know that I’m not alone!

I feel seen and/or personally attacked by this article. I am Jack’s Schrödinger’s cat.

I look at it this way: I am supporting authors by buying their books. It is the best rationalization money can buy

I’m like one of those people who lived through the Depression and had cases and cases of food when they died. I’m a voracious, omnivorous reader and the stretch in my life when I only had a dozen or so books (which I re-read over and over again) has left its mark. I have 1000s of books. Fortunately, I have a room in my house where I can store the hundreds of physical books I own (which include books my sisters bought), so there’s that. I have ebook duplicates of physical books I own. The deep fear I have of having nothing to read is assuaged by my treasure trove…

My own TBR books generally are of the non-fiction type…

This has a wonderful rationalization build into to them – akin to Trike#8 – I’m supporting the author by buying her book!

My rationalization is that “They are reference books! I’m going to need to know this one day for a project be it fiction or an essay so then it will be right there where I need it!”

Now, the good news is that this is often the case – well…okay it seems that way through the lens of selective memory.

Or how about: “I must be smarter than I think since I have all these books on all these topics!” (Another useful rationalization!)

I am right now reading a book that is about a year or more old on the TBR shelf and I am enjoying it immensely! Which of course just reinforces my addictive behaviour of buying those tempting books on so many topics…

I’m getting better in that a book that I tried to read repeatedly and thoroughly disliked I put in my give away or resell pile!

Unless the TBR pile is big enough to crush you if it tips over, you don’t have too many book in it.

Eyeballs TBR pile, googles for videos on building retaining walls…

12: Miya Kazuki’s Ascendance of a Bookworm begins with said bookworm avoiding death by Truck-kun, only to be crushed when a small earthquake topples her books onto her.

I totally feel this with my TBR pile of books, though I am ESPECIALLY bad about this with video games (my PSN and Steam libraries are basically digital graveyards haunted by the Ghosts of Deals Past). I have tried to become better at not buying books until I’m ready to actually read them, but I will likely never crack open my copy of, for example, Fire & Blood by George R.R. Martin that languishes on my shelf while collecting a prodigious amount of dust.

That being said, you have got to dig into those Catherynne M. Valente small press books that you’ve been neglecting! They are all so good!

I try to keep my TBR around me and my read books in storage, that way when I’m looking for something to read I’m more likely to pick up an unread book because they’re more accessible and I don’t have to dig. It’s a pretty even bet whether I’ll read a book within a week or two of buying it or whether it’ll stay on the TBR until god knows when.

The genre with the most proportional TBR for me is poetry, and then classics and literary. I have more books in terms of number (both read and unread) from SFF but almost all the poetry books I bought I have not read beyond a page or two.

When I was younger and had much more free time, whenever I finished a book I used to go to my local bookstore and browse for hours until I picked out the perfect next read.

After college, when I got a job at that same bookstore and routinely got free or deeply discounted books that started to pile up and beckon to me forlornly like half-forgotten friends, I set a rule for myself that I would only buy a book if I was going to read it now — otherwise I would add it to a wishlist (of which I have several, organized by genre and level of desire).

Nearly ten years later, I can say I’ve held to this rule pretty well.

Has it solved the problem? Sort of. Like the author, the books on my TBR tend mostly to be the books that I already had when I established my rule (hi there, Mahabharata). And I almost always buy recent additions to my wishlist (ooh, She Who Became the Sun!) rather than the ones I’ve been wanting to read for ages (someday soon, Lost History of Christianity). But it has reduced the clutter on my bookshelves and diminished the feeling my TBRs give me that I’m neglecting important homework.

Conclusion: it would be a great plan if the internet wasn’t a thing and I didn’t learn about an exciting new book almost every week.

Anyway, back to SWBTS.

Nice article on a topic close to many reader’s hearts.

And talk about coincidences. The next book I’m reviewing for TorDotCom is A Canticle for Leibowitz by Walter M. Miller, Jr., a book I started about 50 years ago, and only finished last week. So I know a bit about leaving a book in the TBR pile.

One thing I have learned over the years is not to shop for books based on price. When I buy a book because it is a bargain, it will almost certainly end up on the TBR pile. If I really want to read a book, I will buy it when it is published, and pay full price for it.

I’m reminded of a book reviewer at an F&SF convention, many years ago, who told the story of when a bookcase in his barn (where he kept ALL the books he’d read) fell on him and trapped him for several hours until his wife came home and found him.

There *is* such a thing as too many books, he said, when they’re on top of you.

I did enjoy reading this. My TBR now tops 1k and I am seriously starting to believe I may no Longer have time to read them all. Now there is an unsurmountable problem. LOL

I love the feeling of potential in my TBR stack eBook collection. I went through a period of about six years where modern English language fiction, particularly genre fiction was hard to come by, due to living abroad before eBooks really took off. So a stock of books that I’m interested in and haven’t read yet is a luxury.

Like a previous commentor, I use calibre to manage collections, with several categories for TBR – one for newish releases, one for older stuff I picked up cheap (I just started working my way through a complete set of Fafhr and the Grey Mouser that I slowly collected from Kindle deal of the day sales), and public domain stuff from Project Gutenberg and Faded Page.

For me, Theodore Sturgeon put the matter to rest succinctly when he gave these words to Mr. Spock: “after a time, you may find that having is not so pleasing a thing, after all, as wanting. It is not logical–but it is often true.”

I love this so much and almost feel I could have written something similar myself. I too keep my TBR pile stacked with spines away, and I constantly dream about actually having enough time to read EVERY. SINGLE. ONE. of them. But you really musts read The Only Good Indians. Grab that one out of your TBR right now. You’ll thank me later!

There’s also the anticipation of…loneliness…in reading a book that’s been waiting for a while. Personal example, I have Sarah Monette’s Corambis in my TBR pile, and it’s been there for almost three years. After flying through the first three books in the Doctrine of Labyrinths series, I was delighted to find a copy, since my library didn’t have it. And yet I still haven’t read it, because I know that once I do, the series will be done. No more Felix, no more Mildmay, no more of the dark and fascinating world I like so much. I can’t quite bear the thought of closing that door, so I go read something else.

I have to admit that even though I have multiple bookshelves and book piles, I’ve read almost every book I own. I tend to preorder the books I want so I get them delivered on release day. The anticipation is such that I start reading at once and read until completed unless I absolutely hate the book. That hasn’t happened enough for me to have a significant “started but not finished” pile. What I do have is a substantial “to be reread” pile that I wonder if I will ever complete.

My tbr pile is kept small by the experience of sorting through Dad’s stuff after his death, and then helping a friend sort through his mom’s stuff after her husband died and she was downsizing. The latter, especially, encouraged me to get rid of all the Stuff I didn’t need or use. We’d meet up, fill the F150 (he’s a farmer) and haul the Stuff to either Goodwill or landfill. Every Saturday. For three months.

If it’s been on the tbr shelf for more than a year it goes off to the dollar table at the local library.

This makes me think of my TBR list and at best, there are some there I haven’t read because the library doesn’t carry…anymore. Because they’ve been there so long or I learned about them after they circulated out.

But I also have a pile of physical books that are unread. Nowadays its largely books I back on Kickstarter and was super interested in at the time I backed it, but months or years later when I get it…not so much. (Hoping Dave Kelett’s Drive Volume 3 gets me to read 1 and 2, though I said that with 2 getting me to read 1.)

It doesn’t help that 2020 killed my reading pace. In ’19 I had 34 books read, in ’20 I had 19. I’ll be lucky to hit 2/3 of my goal of two a month at my current pace.

So….yeah. My cupboard is full and I’m probably going to have to donate some to the local friends of the library to make room.

You definitely have too many tbr books if the pile starts on the floor and reaches your chin, as with a friend of mine

I appreciate this article and thread of comments, which are letting me know I am not alone with my physical shelves of TBR, ebooks languishing on the reader, and multiple lists – one for the library, one to buy…

No one has mentioned a problem that I sometimes get, choice paralysis. If it’s one time, I’ll write down the top contender books, number them, and roll a die. If it’s ongoing inability to choose, I’ve used a made up rule for a while, like must alternate ebook with paperback, or fiction with nonfiction, or f/sf book with something outside the genre.

I wonder whether those weird habits have helped me avoid the issue of books becoming less shiny as they sit on my TBR.

Judging from the other comments I’m in the minority, but I don’t experience this effect that having books around for longer makes me lose interest.

I have so many books to read that I’m also afraid I’ll never manage to do so in my lifetime but the vast majority is in my possession because I want to read them.

Book talks often remind me of particular books and usually my reaction is “Oh, yes. I really should read that one soon!” but this happens more frequently than I can read the books in question so there always remain loads of these.

For most books, it makes me want to read them more, not less. The immediate thrill of a very newly bought book will wane, sure, but generally not the overall interest.

Frankly, it’d be a catastrophe if that happened because that would mean that I got all those books in vain…

Oy vey iz mir! Between bought and not read (some spending decades in that purgatory), the list on my library database, the list on Goodreads of books not in my library system, 1,000 titles has long since vanished from my rear view mirror. At least I was able to transition my compulsion from buying them to putting them on lists before my wife divorced me. For a few brief years early in my life it seemed as if there was a possibility of me running out of things that I wanted to read. Old (like me) science fiction fans speak of the days when, with diligence, you could keep up with all of the important work in the field. That was no longer the case even by the 1970s, but the anxiety still haunts me and I can’t get rid of it, even though I know that it is completely irrational.

I’m not at all bothered by having stacks of unread books around me: I love knowing that I will be able to immediately lay hands on a book when I am ready for it.

@2/allthewayupstate: Squeeee!! Enjoying reading your comment and then you bring up a wonderful, unappreciated gem — Mona Clee’s Branch Point (allow me to also tout her excellent and extremely prescient Overshoot, a turn-of-the-century warning about the horrors and sadness of runaway global warming). My affection for Branch Point illustrates a reading dilemma of mine that I imagine many others share when considering the TBR stack — what about the read-already-and-coming-back-for-a-second (or-third) -helping books? When I want comfort food (and who hasn’t recently?), I’ve got a shelf or two of tried-and-true rereads I will eagerly reach for. Sure, it’s trading off the warm experience of revisiting an old friend against the possibility of discovering and cherishing a new classic (to be read again itself, no doubt). That practice definitely adds a TBRR stack to one’s burgeoning collection.

Don’t be this guy….. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0734683/

My tbr is measured in walls, and that’s after recent major purging. The walls that used to be double-rowed up and down are now [mostly] single-rowed. Major progress, that.

This topic plagues my anxiety weekly, if not daily. I have (embarrassingly) 800+ print books on my TBR, over 1000+ ebooks on my TBR, and another 500+ review books to tackle. I will (quite literally) never, ever catch-up. And yet what did I do this past weekend: went to the bookstore and bought 6 more books!!

It shocks me every time I enter my basement and see the stacks and stacks of unread books. And yet at the same time I LOVE to look at them. The possibilities behind each cover and how beautiful they look on the shelf. Some of the books on this shelf are over 15+ years old. I try to whittle the list down each year (at a minimum). This past pass I pulled 30 books off the shelf to donate or sell; and yet it barely made a dent.

I too have spreadsheets, use Goodreads, and a handwritten notebook to keep track of my obligations and different TBR lists. And I too am distracted by new review books being sent to me, library holds coming available (which is silly because if I didn’t have enough interest in the book to buy it why am I prioritizing reading it?!), and by my mood or desire at the moment I pick a new book.

I’ve seriously considered turning the spines all in on my shelfs (as they are double and triple stacked I can only see a portion of the books anyways) in an effort to blindly choose my next TBR and force it to be off my shelf. Maybe that will work some. I have started the exact idea in this article which is that I read a ‘older’ book off my shelf alternating with newly published (often review) copies. I hope to keep this up and make small, minute dents in my lists.

I have often asked myself why I still buy books when I’m already anxious about how many I have to read at home. The answer is: because I love, adore, and get such wonderful pleasure from having new books. Again, new possibilities, learnings, and that somewhere I have bought my next favourite book. Now I just have to get around to reading them to determine which is my next book to recommend to everyone I know.

I almost marked your post as something “to read later”- the irony face-palmed me and I read on! People often comment on all the books in our house. I sometimes say, “well, it would be more impressive if I’d read more of them!” Hence, my New Year’s Resolution tradition. I walk around scanning the bookcases and make a list of ten major or minor classics I have not read and commit to at least those. Do I actually complete my resolution book list? Weelllll…. sometimes!

Wonderful article. I certainly have lots of unread books, complicated by keeping up with library books and ebooks. Pandemic brought many more books ordered and more unread. I weed books severely over a move and won’t keep a book if I will not reread it. Still have large piles around apartment as a result of heavy buying even while reading up to four books a day. Agree less eager to read books on pile the longest, but sometimes am pleasantly surprised. Will not throw out simply due to piles. Keep up the good work.

I have one short bookshelf that I limit my TBR pile to. If the shelf fills up I have to read some before I let myself buy anymore. It can fit about 150-200 books on it. I also really try to look at it at the end of each year and be honest about what books I’m just not going to read. But I have also had the joyful experience of grabbing something that has been there for years and LOVING IT- and then going “dang why did it take me so long to get to you?!”

I’m also really picky about what books I like enough to keep on my read shelf. If a book doesn’t catch my heart in a “oh my god I love it” way then it goes to the used bookstore and doesn’t stay in my house.

But like everyone else commented- glad I’m not alone in my book buying tendencies!

Great article but the ending question for some reason gives me a sense of anxiety.

“But the part of my brain that loves completing tasks and shelving books I’ve just read sometimes stares at the unread-books wall and wonders: What would it be like to catch up? To read them all? To clear the slate?”

Nope, I don’t want to catch up, I don’t want a clear slate. I think I like the fact that there’s always another story waiting in the wings that will suit my mood or entice me to read something different. There’s always a reason why I add a book to my stacks, some for pure joy, others for enlightenment, education. But just like when I’m reading and get an epiphany, but forget to highlight or write that information down, later when I peruse the stack and see that book, the reason escapes me and makes me wonder what the heck was I thinking.

My TBR is about 1100 books deep — real dead-tree books. It’s two bookcases and a lot of piles. Reading these comments, now I feel like a noob…

I’m also wondering if I have enough time left to finish these. But fear of not having anything to read overrules.

The situation is made more complicated by my wife, who reads a book a day. She’s afraid of not having anything to read as well. I’m reasonably sure we’ll finally die with a big collection of not-yet-written books to be read. Than they can become someone else’s Mount TBR!