God is dead, his corpse hidden in the catacombs beneath Mordew…

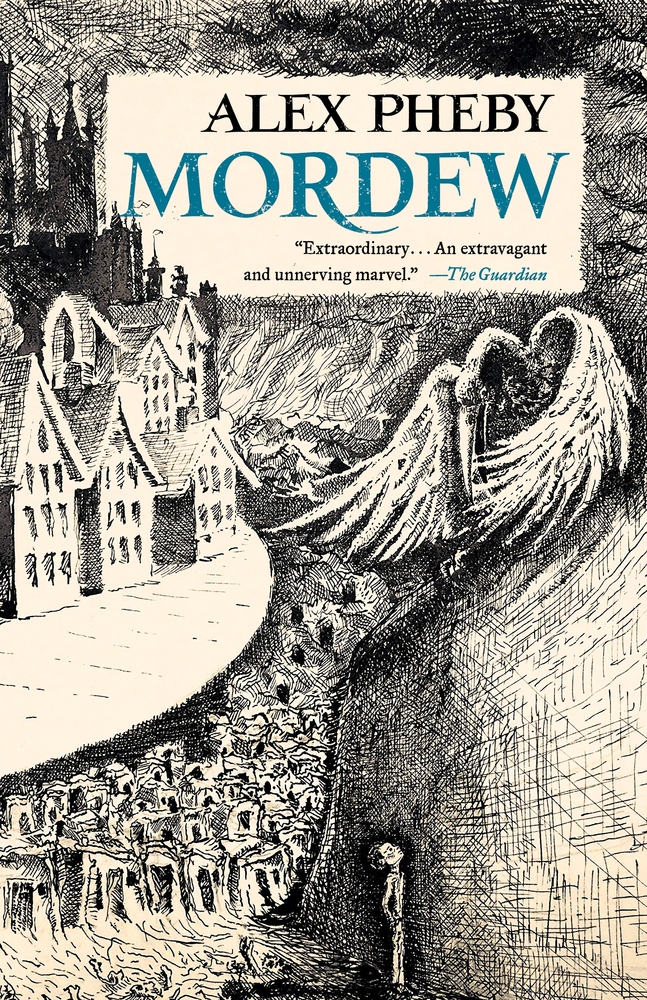

We’re thrilled to share an excerpt from Alex Pheby’s Mordew, the start of an astonishingly inventive epic fantasy trilogy full of unforgettable characters—including a talking dog who wants to be a philosopher. Mordew publishes September 14th with Tor Books—start reading chapter seven below, or head back to the beginning!

God is dead, his corpse hidden in the catacombs beneath Mordew.

In the slums of the sea-battered city, a young boy called Nathan Treeves lives with his parents, eking out a meagre existence by picking treasures from the Living Mud and the half-formed, short-lived creatures it spawns. Until one day his desperate mother sells him to the mysterious Master of Mordew.

The Master derives his magical power from feeding on the corpse of God. But Nathan, despite his fear and lowly station, has his own strength—and it is greater than the Master has ever known. Great enough to destroy everything the Master has built. If only Nathan can discover how to use it.

So it is that the Master begins to scheme against him—and Nathan has to fight his way through the betrayals, secrets, and vendettas of the city where God was murdered, and darkness reigns.

VII

The bucket brought them out, blinking, into the light. Before they could focus, they were dragged onto cold white tiles and the bucket carried on over a cogwheel, descending the way it had come without a pause. The whole ceiling was white with light, one solid block of it. The three children were lined up on the white floor.

‘Where’s the hot water?’ a woman shouted.

‘Waiting for you to draw it, you stupid cow,’ called another.

A third came over with a pair of tailor’s scissors, snipping the air around them, crab-like, interrupting the conversation. ‘Should I strip ’em or shear ’em?’ she called.

‘Both. And, for His sake, hurry. There’s more of them on the way.’

The woman shoved Cuckoo apart from the others, slipped the scissors between his plump waist and the waistband of his trousers.

‘Oi!’ Cuckoo cried. ‘Watch it.’

Buy the Book

Mordew

The woman stopped and cast an eye over him. She was dressed in blue checks, with her hair contained behind a scarf, pulled back so tight that her mouth couldn’t quite shut. Her teeth were dark like varnished wood. She closed the scissors and Cuckoo’s trousers fell to the floor. She gave him a withering, appraising once-over. ‘You’ve got plenty where you don’t need it, and none at all where you do. Anything I snip off will be doing the world a favour. Arms up.’

Cuckoo held up his arms and the scissors traced up to his neck, letting the rest of his clothes fall as they went.When he was naked, she shoved the scissors into her apron and pulled out a razor.With this she took the hair from his head. Cuckoo hid his shame the best he could.

‘Get the broom and sweep that muck into the hole—it’s crawling with Mud. Don’t worry. The Master’ll kit you out in new gear whether he keeps you or not.’ She shoved him in the back, towards where the broom lay. ‘Next! You.’

The girl clung tighter to Nathan, breathing as if she had run a mile.

‘Come on.You think I’ve got time to waste on the modest? If you had an idea what kind of sight you look, you’d be glad to get cleaned up.’

Nathan took the girl’s hand and eased it from his collar.

‘She some kind of flap-lapper?’ the girl hissed. ‘She tries anything funny, I’ll kick her in the ducts.’

‘I don’t know,’ Nathan said. ‘It’ll be fine.’

‘Ain’t that sweet?’ the woman said. ‘Two lovebirds chirruping. Now over here.’

The girl set her shoulders and went. Nathan turned away as they undressed her; he wasn’t sure why.

‘Hah! You’ve got less than him.’

‘Shove it up your slit!’

‘Shove what? Get over there.’

When it was done, and Nathan too, one of the other women doused them all with hot water.

‘Take a brush and scrub. When you’re sparkling free of dead-life I want you dressed.’ She indicated a bench with pegs on the wall behind, from which hung white smocks like headless ghosts. Before she could say anything else, three of the other boys were up on the bucket and the women rushed to tend to them.

Where the children had once been like scarecrows, mud-caked and damp, they now seemed like porcelain dolls, fresh from the kiln, before the hair is needled into the scalps. They stood in a line, white-smocked, bare feet splayed on the tiles. The women went up and down, scraping stray hairs here and trimming nails there.

‘Is Bellows ready for them?’ said one.

‘Are they ready for Bellows? That’s the question,’ said another.

‘Shall I see?’

When she returned, she went down the line, a licked thumb wiping smudges and nails pinching motes of dust.‘You’ll have to do, but I can’t see Bellows smiling at the sight of any of you.’ She came down the line and stopped at the girl. ‘And you, little sister, can forget it. He smells oestrus from a hundred yards and the Master won’t tolerate female stuff. It disrupts His equilibrium, he says, and puts His work in a tizzy.’

‘I’ll put that rod-rubber in a tizzy, I’ll…’

The woman hushed her—‘Bite your tongue, child. I won’t give you away—we have to look out for one another—but Bellows can’t be fooled, and he sniffs out even the girlish amongst the boys, so he’ll sniff you out too. What’s more, he’s no joke, and this place is no joke neither, not for me and definitely not for you. The only girl up there is Mistress’s daughter…’

‘That’s just a rumour; you’ll believe anything,’ one of the other laundresses cried.

‘I believe what I know—Bellows’s brother brought her back and now the Master keeps her locked up, quarantined.’

The other woman pulled a face and rolled her eyes.

‘You don’t believe me? I’m from Malarkoi, so I know. That’s why the Mistress sends her firebirds, hoping to get Dashini back again.’ The woman looked up, suddenly, through the ceiling to where the Master must be. She tugged at her lip, worried perhaps that she’d said too much.When she wasn’t immediately spirited away to answer for her treason, she turned back to the children. ‘Anyway, be civil or prepare for the worst. Time for you to go in, and I’m going to take you. Behave! No crying and wailing, and no pleading if Bellows won’t let you through. It won’t serve anything except for getting you whipped. Bite your tongues and you’ll soon be done, one way or the other. Should say, I suppose, that the Master has taken few recent, and of them there’s been some discards, so I reckon there’s a fair chance He’ll take some of you. Whether you think that’s a good thing or a bad thing, I don’t know. All depends how much you need a shilling, I suppose. Follow me, nice and neat now.’

She led them through the door into a corridor panelled with wood along which moved all manner of traffic: men with trays, men pushing carts, men rushing in one door and out another, each of them dressed the same in tight black frock coats with high-buttoned necks. Nathan was relieved at least to see they were not eyeless and had no gills, and that when they spoke, they spoke through their mouths.

‘Mind aside,’ one might say, or ‘Behind,’ and there was nothing strange to it other than the speed they all moved at, and the urgency they showed. The woman lined the children up against the wall.

‘I best go now. Womenfolk aren’t tolerated long this close to the Master’s quarters, and I’ve no requirement for a beating. Remember what I said, and best of luck to you, whatever it is you’re hoping for.’

With that she returned to the grooming room and they were left in amongst the never-ending flow of people with urgent things to attend to.

The girl was a few places away, her head down and her teeth gritted. Nathan wanted to go to her, but each time he made to move, someone would sail too close to him, or a trolley would clatter past. Beside him the crybaby wept, and on the other side Cuckoo grabbed his arm.‘Is this him? Bellows?’

A figure came towards them down the corridor—it would be wrong to call it a man—with arms and legs as thin as birch branches. He was hunched over and moving as if his knees bent back rather than forward. He was dressed all in black with gold brocade. He wore a tall hat that rested on the bridge of a huge nose the size of a man’s hand held upright and perpendicular to the face. The nose was like an oar blade, or a rudder, and it was this that came foremost. If the man had eyes, they were not visible from under the hat. If he had gills or a mouth they were hidden under a high starched collar. The traffic of the corridor parted when it saw him, never coming within a foot of him to either side. Not one of the men looked up at him, all of them averted their eyes as he came along.

When he was ten feet distant, he stopped, one hand rising immediately into the air, the fingers outstretched. ‘Ah!’ he said, ‘Bellows’s nose sniffs out a girl-child. Not a crime to be a girl, in and of itself—certainly not. Without girl-children the world would be in a perilous state, one possible supply of boy-children, in due course, being thus endangered. But is not the Mistress, our enemy, of the female persuasion, this fact bringing all of that sex into disrepute? Still, do not despise yourself.You will be judged on your actions, not by accidents of birth. Yet now, for the Master’s purposes, you are worse than nothing.Your proximity would chafe on Him. He does not trouble himself with smells—for that He has Bellows!—but the female reek is so pungent it makes the very air tremble. Again, do not let this disturb you—many malodorous things have a use. Some cheeses. Ammonia. It is simply a fact. Closet yourself with your own kind for now so that you least inconvenience those around you.’

Bellows moved forward, and as he did so his finger indicated the girl. Instantly one of the men around took her away. She struggled and spat and looked down the line. ‘Get your hands off me, you noncer!’

Nathan went for her, automatically, but another man came from nowhere to restrain him. Nathan felt the Itch, let it run across his shoulders and down to his hands, ready for Scratching, but the air was thick, and it stifled. He hit out with his fists, but with no great strength.

‘Wonderful!’ said Bellows, who had been watching the proceedings with an air of delighted amusement. ‘That a boy-child should feel the loss of such a creature, against all odds, is noble. And practical too. For, if it were not so, would not the generative congress that might eventually take place be otherwise unbearable?’ Bellows advanced, his nose cutting through the air as the prow of a boat cuts through water.When he was still a little way away from Nathan he stopped. ‘Was the girl’s stench so strong? That it should mask this?’

The crybaby cried even harder, thinking Bellows was coming for him, but his attention was on Nathan. He stood before him and raised his nose a little, as a vintner does before assessing a freshly opened bottle of wine.When the nose was at the correct angle, there was a whistling intake of breath as Bellows’s nostrils flared, opening black immediately in front of Nathan, who could not help but cringe.

‘Unprecedented! So rich. I have no doubts.’ Bellows put his hand on Nathan’s shoulder, and he was taken from the line and placed off to one side.‘Weeper.You will know, I suppose, of the potency of tears in the making of certain solutions? You may well be chosen.’The crybaby was also taken to the side. ‘You will not be required, fat one. There is about you the stench of guano and sour dripping. The Master will not see you. Of the rest, there are only two who might serve—perhaps in an ancillary function.’ Bellows laid his hand on them in turn. ‘You others, return to your places of dwelling with happy hearts.You have come within a few rooms of the Master of Mordew. You have been fortunate enough to share your existence with His and, while you might never come here again, you will know, in part, what majesty the world contains. What wonder. Let this comfort and sustain you throughout the remainder of your painful existence. Should you ever feel unfortunate, recall this day and do not forget the privilege that has been accorded to you in coming here. Now, leave as quickly as you may in order that you might the sooner appreciate your present luck, in contrast with the gross drudgery that exists without.’

The ones who had not been chosen were spirited off by men at Bellows’s instruction until only the four others remained.

‘And you, my boys.You cannot imagine your good fortune yet, having no way of understanding it. But within the hour you will have stood in the same room as the Master. Who knows, perhaps you will have received more even than that.’

Nathan strained to see where the girl might have been taken, but he was shoved forward, and made to follow Bellows, who slunk and loped down the corridor with the other boys behind him. As he went, he declaimed: ‘Oh, how I envy you, boy-children. To be in that wondrous state of nervous excitement. To anticipate the appearance of a legend, no, a demigod and not yet understand how little His reputation does Him justice. How greatly He exceeds even the most hyperbolic of those rumours that you will have heard. Approaching the divine, blasphemous though your witch-women will decree such a notion.Yet they are ignorant, are they not? Never having seen Him. If they beheld the Master, they would cast aside their misheld faith and worship Him instead. As I have. Once I was as you are—unaware, unprepared—and if it were not for His continuing magnificence, which is boundless in its ability to astound, I would return to that state in an instant, to once more appreciate His wonder from the viewpoint of one whose eyes had never been opened. As a blind rat who first sees the sun. And so, in awe, appreciate most fully His wondrousness.’

Bellows halted at a doorway and turned. The boys stopped in their tracks and the nose sniffed for them, arms either side beckoning.

‘Come forward. Beyond this door lies the antechamber into which the Master will manifest Himself.’

The boys did not move.

Bellows nodded, the nose tilting gravely as he did. ‘Quite right.You wonder now if you are worthy.You wonder if you, in your grossness, in your ignorance, in your poverty, have the right to stand before Him. Let me tell you that your concerns are correct. You are too gross. You are too ignorant. You are too poor. There is nothing in you that is deserving of the Master’s attention. And yet… the same thing could have been said of me.’ Bellows crouched down so that the nose was at the level of the boys’ heads. The nostrils pinched and relaxed in a mode that suggested the restraint of great emotion. ‘I was like you once. Small and ineffectual. I, too, believed I was without worth. I, too, quaked at the prospect of entering the Master’s service.Yet look at me now!’ Bellows rose up, clenched a fist and held it high above, his nose inclined to the ceiling. ‘The Master has transformed the base metal of my being into the purest gold. In my service to him I have been elevated out of the dirt, up to a higher purpose. Stand proud then, boy-children. Not for what you are, which is nothing, but for what, with the Master’s grace, you may yet be.’

Despite Bellows’s exhortation, the boys did not stand proud—quite the opposite—but Bellows seemed not to notice. He held the door open and reached with fingers like briars to shepherd them through.

VIII

The antechamber was vast; it was so wide and white that it was difficult to see the other side. Nathan blinked and turned his head, hoping to make some invisible detail come to light or cause a clarification by shift.ing his angle, but it seemed rather as if they had entered a world of whiteness, blank and plain.When Bellows shut the door behind them, the illusion was complete; on all sides there was nothing, seemingly, to distract Nathan’s attention. Except, perhaps, at the edge of sight, a blurring, here and there, although a blurring of what it was impossible to tell.

‘This room the Master made to buffer His quarters from the ordinary realms of men. It is the only entrance, and it takes many minutes to cross. Attempt no such crossing in your eagerness, boy-children. There is one path only through this room, and that is marked out not by things visible, but things only those qualified may sense.’ Here the nose swept from side to side and Bellows nodded slowly.‘It is understandable that you might seek to rush to the stairway that leads to His door, but should you do so you would find yourself rendered dust in an instant. The Master has laid filaments impossibly thin across the greater part of this room, so thin that light does not trouble to illuminate them but passes to either side. Should you cross these filaments you would find yourself in the position a peeled, boiled egg finds itself in a slicer: before you knew it, you would be dead. An interesting question presents itself. If a man is not aware of his death does he feel himself to be still alive? If you wish to find out the answer to this question, you need only cross this room unaided. There is a passageway, I can apprehend it clearly, but that is my privilege alone.’

Nathan wiped his eyes with the hem of his smock. There was a definite blurring visible to him. If he turned his attention away from the room and focussed on the tip of Bellows’s nose as it described slow figures of eight as he spoke, if he concentrated here and did not turn, there were spiders’ webs, or something very like them, across the whole room.

‘If the Master lays His mark on you, I will accompany you to his door. Do not leave my side! The passage is only wide enough to allow three abreast; if you dilly-dally or fidget, or struggle to run forward in your delight, you will not live to regret it.’

Nathan could see the path. If he turned to observe it directly, it dissolved away, but if he kept looking away, he could follow it, left and right across the antechamber.

‘I am nimble,’ Bellows continued, ‘but not as nimble as I once was, and long years of attending to the needs of the Master have deprived me of that understanding of the animal cunning you boy-children possess. I make no apologies for that. I will, if against the dictates of reason, you attempt flight, try to stop you, to restrain you for your own good and the convenience of the Master, but I cannot guarantee my success. Only you can be the guarantors of your own safety. When the Master appears, restrain your emotions, and restrain your movements.’

As if on cue, on the other side of the room a door opened, visible in outline against the white. Bellows drew in a great breath, all at once. ‘He comes.’

In through the door came a shadow. Though at a great distance, it was very clear against the blankness. It was a man’s shadow. He stood in the doorway, tugged at his sleeves and adjusted the lie of his jacket—his arms were not unusually long, and they jointed in the proper way. He put one hand up to his head and smoothed back his hair. He wore no tall hat or stiff collar.When he reached to straighten his tie there was nothing uncanny in his movements in any way.

And then, immediately, he was in front of them, not need.ing, seemingly, to pass through the intervening space.

‘Good afternoon, gentlemen,’ he said. His voice was calm and pleasant, like a kindly uncle’s might be. He wore a very ordinary suit, cut to a standard pattern, respectable and unostentatious. He was Nathan’s father’s age, or thereabouts, though much better preserved.

Bellows bowed so low that the tip of his nose smudged the ground in front of him.When the Master begged him to rise, he wiped the mark away with his handkerchief.

‘Really, Bellows, there’s no need for all this formality.’ He turned to the boys. He had an affable face, open, with an attentive set to his eyes. He paid the first boy in the line, the crybaby, as much attention as one could expect a man to pay anyone, no matter how important.

‘Young fellow,’ he said, ‘what can we do to cheer you up, do you think?’

The crybaby looked up, the tears shining on his cheeks. The Master smiled and the boy held his gaze.

‘No need to cry now, is there? It’s not as bad as all that. Would you like a lolly?’ The Master held one out, though where it had come from, Nathan couldn’t say. The boy did not move, but he licked his lips. ‘Go on, I won’t tell anyone.’

The boy reached out and took it. As he did there was a movement, too fast to see, but when it was over the boy’s face was dry. Nathan blinked, but no one else seemed to notice anything. The crybaby, crying no more, popped the lolly in his mouth. The Master smiled and nodded to Bellows. ‘See, Bellows,’ he said, ‘my lollipops are excellent medicine for a case of the grumps. Fortunately, I have an unlimited supply.’To prove his point four more of them appeared. One he popped in his mouth, another he offered to the next boy in line.

‘And who are you, sir?’

‘Robert,’ the boy said, taking the lolly.

‘Well, Robert, are you the type of chap that enjoys an adventure?’

‘Depends,’ Robert said.

The Master smiled and nodded again to Bellows. ‘I’d be willing to bet that you are, and I have just the position for you. How would you like to work for me on my ship, eh? I think I’ve got just the job for you.’

‘Depends,’ Robert said.

‘Of course it does.’ The blur again, impossible to see, across the length, then the breadth, then the depth of the boy.‘I think you’d fit the position perfectly, and all the lollies you can eat.’

Again, the Master did not pause for so much as a fraction of a moment and no one reacted in even the tiniest way. The blur was like the spiders’ webs—not seen straight on. Nathan looked over at the doorway and kept his eyes focussed there intently as the Master turned his attention to the next boy.

‘And you? Have you ever considered a career in horticulture? I have some very rare blooms that require nurturing.You look like a boy with green fingers. May I see?’The boy held them out and then Nathan saw it. In a fraction of a second, the Master took from his jacket a needle and pricked the boy’s palm with it. A drop of blood was raised. The Master took it with his fingernail and put it to his lips, then his hands were where they had been, as if nothing had happened.‘Wonderful! I see great potential.You have the essence of a head gardener in you, that much is clear. If you put all of yourself into it, I’m sure my plants will grow and grow. And you…’

He turned to Nathan and became still, his mouth frozen around the syllable he had been uttering. Then his face seemed to melt, only a little, but enough so that everything about it drooped—the joining of his lips, his cheeks, his eyelids. He coughed, and everything returned to its proper place.

‘Bellows,’ he said. In his voice there was something of the frog’s call—a croakiness, as if his throat was uncomfortably tight. ‘Who do we have here?’

Bellows edged forward, not bowing as low as before, but still bent over. ‘I’m afraid, sir, that the child and I have not been introduced. He has the odour of an Inheritance about him. Quite strong. A very interesting specimen.’

The Master nodded, but his eyes remained on Nathan. He did not look away, not even long enough to blink. ‘From where was he brought?’

‘He came with your Fetch from the South, as did they all.’

‘I see.Young man, what is your name?’

The Master leant forward. His eyes were deep and brown, but the whites were threaded with veins. His skin was coloured with powder, and where the powder was patchy, grey could be seen beneath—the grey of a man who worries, or who does not sleep enough. The collar of his shirt was a little grubby, and now he seemed much more like Nathan’s father—harried, unwell.

‘My name is Nathan…’

The Master put up his hand. ‘Treeves,’ he finished.

Nathan nodded, but the Master had already turned away.

‘Bellows. These three I can find a use for. The last… no.’

‘But sir!’ Nathan grabbed the Master’s sleeve. The Master turned, and Bellows froze, dismayed. The Master stared at Nathan’s hand as if it were very unusual indeed. Nathan drew it back. ‘I must work for you. Mum says so. Dad is ill, and without the shillings for medicine he will die. She has no bread for either of us.’

The Master examined Nathan closely. ‘Do you Spark yet?’ he said.

Nathan was silent, startled to think this man knew his secret business. He wanted to say no, to hide his shame, and he tried, but his head nodded despite him.

‘Well, don’t,’ the Master snapped,‘if you know what’s good for you. Bellows, take him away.’

Bellows took Nathan away before he could say another word.

Excerpted from Mordew, copyright © 2021 by Alex Pheby.