As with all authors my own work has been influenced by the writers I have read, particularly those I read in my childhood and early adulthood. I’ve written about this before, and many of those influential authors are fairly obvious simply from my age and their visibility in the late 1960s and 1970s. Writers like Ursula Le Guin, J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Susan Cooper, Diana Wynne Jones, Alan Garner, Joan Aiken and many more, who were incredibly important to me and whose work I still re-read and who have been and continue to be a strong influence.

But for this article, I decided to pick out four books and authors who are now generally not so well known—and certainly not as well known as I think they should be —whose work also had a great influence upon me.

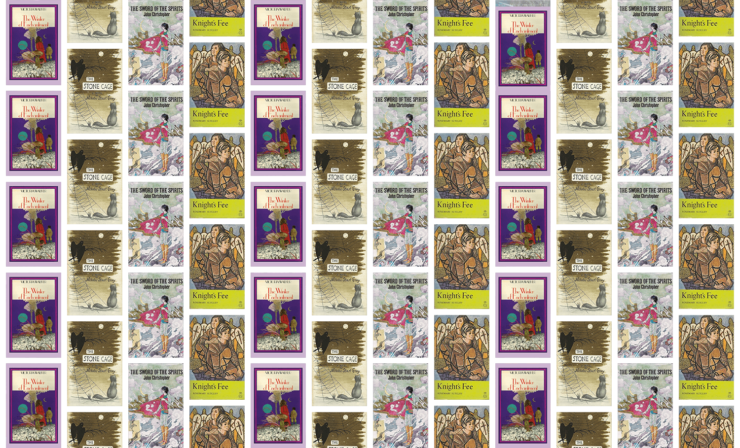

The Winter of Enchantment by Victoria Walker

I read this not as a library book, but a paperback I bought myself with my own money, probably around the age of ten. Buying a book was a relatively rare occurrence for me at the time, the vast majority of my reading was of library books from either the public library I dropped in to every day on the way home from school, or the school library itself. The Winter of Enchantment is a portal and quest fantasy, in which Sebastian from Victorian-era London teams up with Melissa, imprisoned in a magical realm, to try and free her from the clutches of the Enchanter. To do so they have to collect five Power Objects, the first of which is the Silver Teapot which winks at Sebastian and sets the whole story in motion.

There is also a magical cat called Mantari. Although he isn’t a speaking cat, he was probably one of the progenitors of Mogget in my Old Kingdom books. (I relished that Mantari had become a Power Object by virtue of eating the Silver Fish, this made perfect sense to me.)

I loved this book so much that a few years after first reading it I adapted aspects of the story for a D&D adventure (the Power Objects, the Enchanter, the imprisoned maiden named Melissa, but all set in a much more combative environment) which I laboriously typed at the age of twelve or so to submit to Dragon magazine, in one of my first attempts at gaining paid publication. The fact that this masterwork was seventy pages long in single line-spacing and it had a dozen not very well drawn maps may have contributed to it not being taken up!

The British paperback publisher was Dragon Books, and the dragon colophon was coloured for either reading age or genre or maybe both. This book was a Red Dragon, and there were also I think Blue and Green Dragon books. I went looking for some of these but as I recall the few I found did not live up to my expectations, an early lesson that publishing imprints are rarely as useful as a guide to reading as one might hope.

For a long time The Winter of Enchantment was very hard to find and very expensive to buy when you did manage to find a copy. Fortunately it was republished back in 2004 by Fidra Books, in part because of a groundswell of renewed interest, much of it led by Neil Gaiman writing about his own childhood love of the book and the seemingly mysterious absence of the author from the publishing world after she wrote The Winter of Enchantment and its sequel, A House Called Hadlows (which is more technically accomplished but I like less, undoubtedly because I didn’t read it as a child). Victoria Walker, now Victoria Clayton, explains her apparent disappearance here.

Despite its relative obscurity, The Winter of Enchantment seems to have had a wide-reaching influence on many contemporary writers apart from Neil Gaiman and myself, with Jo Clayton also writing about the book for this very website some time ago.

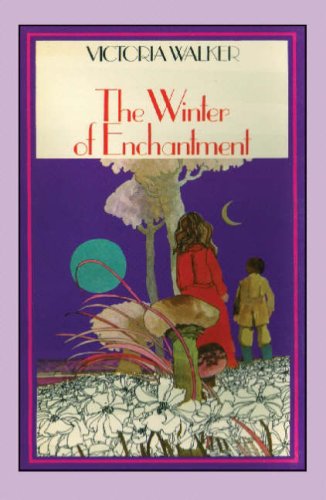

The Stone Cage by Nicholas Stuart Gray

I read my way through every book my local library held by Nicholas Stuart Gray in the later years of primary school, so aged nine to twelve or thereabouts, and I have often re-read them since. All his books are very good, but The Stone Cage particularly stood out. It is a retelling of the Rapunzel fairy tale, but the viewpoint character is Tomlyn, the cat belonging to the evil witch. There is also Marshall the raven, and the relationship between these two is wonderful, with their witty repartee, snarkiness, camaraderie in adversity, and cat to bird animosity.

My character Mogget clearly does owe much to Tomlyn (and Grimbold, another of Gray’s cats, from Grimbold’s Other World) but I think I also learned from Gray something about specificity and matter-of-factness when writing fantasy, that naming things make them feel more real and present (Mother Gothel instead of merely the Witch, for example), and if the fantastical characters like a talking cat sound and behave like people while also being grounded in their animal selves, then they will also feel real.

It is rather astonishing that Gray’s books are not currently in print anywhere, and second-hand copies can be difficult to find and expensive. Hopefully this will change. As a word of warning, sometimes the copies of The Stone Cage which show up are actually the play (Gray was also an accomplished and successful playwright), and have the same dustjacket. The play is interesting, but really only if you have read the novel.

This is another book which had a strong influence on other writers. One of them, my fellow Australian Kate Forsyth, writes more eloquently than I about The Stone Cage here.

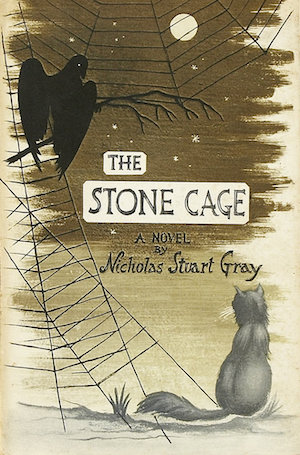

The Sword of the Spirits Trilogy by John Christopher

I’ve cheated a little here, getting in three books for one. My excuse is that I first read The Prince in Waiting, Beyond the Burning Lands, and The Sword of the Spirits all together in a Puffin books omnibus when I was eleven. Many people know Christopher from either his adult SF or more likely his Tripods books, which were relatively high profile when I was growing up, and a bit later in the mid 1980s was adapted as a television series. I liked the Tripods books well enough but in many ways I liked this trilogy more. It is an Arthurian-tinged saga set in a post-apocalyptic England and Wales.

These books would be categorised as YA today, but back then were published as children’s fiction. I definitely didn’t realise at the time how unusual it was to have the protagonist, Luke, grow up to become a deeply flawed individual whose pride, stubbornness, and sexual jealousy is the root cause of a great deal of death and destruction and (spoiler) him not achieving his supposed destiny as the Prince of Winchester. It also does not end happily, though the conclusion is not without hope.

Looking back, I think it was the setting that most appealed to me, the creation of that post-apocalyptic England with its neo-medievalism, Christians as a shunned underclass, seers who were really scientists, horrendous mutated monsters and so on. There is also a grim tone throughout, a kind of somewhat embittered acceptance of both the protagonist’s own failings and those of the world around him. Though my own post-apocalyptic dystopian YA novel Shade’s Children takes place in quite a different setting, I think there is an echo of the tone of Christopher’s books, and I hope the solidity of its creation of a believable world.

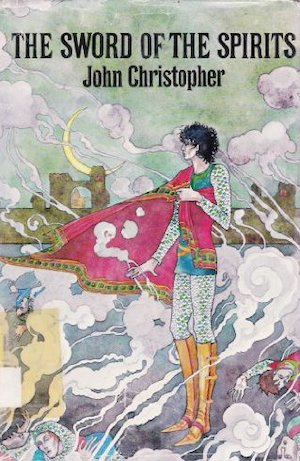

Knight’s Fee by Rosemary Sutcliff

I was, and am, a huge fan of Rosemary Sutcliff’s historical novels. Knight’s Fee is a particular favorite. It is the story of Randall, a Saxon dog-boy who is won in a game of chess by a minstrel who—in the only act of kindness the boy has ever known—introduces him into a Norman knight’s family, where he becomes a companion to the heir of the manor (or fee), Bevis. The two boys grow up together, and learn from each other, and essentially become brothers. It is a coming of age story and of winning out over adversity, but not without cost. Woven throughout is the story of the manor, and how some Normans are becoming part of the deep lore and nature of the land, being woven back into the long Saxon and pre-Saxon habitation rather than being crudely spliced on to it.

Behind the story of the boys growing up winds a thread of intrigue against the King; a Saxon wise woman’s glimpses of the future; and ultimately war realistically portrayed in both its tumult and the grim after-effects, illustrating the darker reverse of the shining ideals and ambitions of young men who want to become knights.

Knight’s Fee is a great example of Sutcliff’s ability to transfer emotion. When I first read it I really felt Randall’s fear and loneliness, and was warmed by his later companionship with Bevis, and the sense of belonging he gains. I could feel this, as I would later feel the shock and grief and acceptance that come later in the story. It was a book I experienced, not simply read. Some authors can do this astonishingly well, often with quite straightforward but elegant prose as Sutcliff does, exactly what is needed to deliver the emotional payload. No more and no less. It’s certainly something I aim to do in my work, and Knight’s Fee provided an early lesson in how to do it. If you can effectively transfer emotion from story to reader, they will remember it forever, even if they forget the name of the author or the title.

Buy the Book

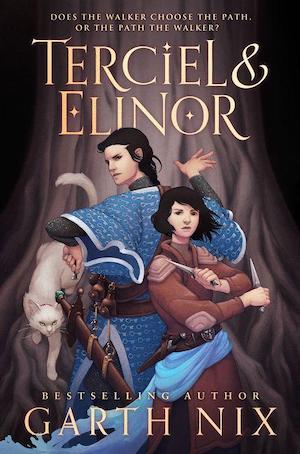

Terciel & Elinor

Garth Nix is a New York Times bestselling novelist and has been a full-time writer since 2001, but has also worked as a literary agent, marketing consultant, book editor, book publicist, book sales representative, bookseller, and as a part-time soldier in the Australian Army Reserve. Garth’s many books include the Old Kingdom fantasy series, beginning with Sabriel; the sci-fi novels Shade’s Children and A Confusion of Princes; the Regency romance with magic Newt’s Emerald; and novels for children including The Ragwitch, the Seventh Tower series, the Keys to the Kingdom series, and Frogkisser!, which is now in development as a feature film with Fox Animation/Blue Sky Studios. You can find him online at his website.