As anyone who has ever had to pry bits of shattered Pyrex out of the walls can attest, experiments do not have to be successful to be interesting or worthy of attention. Publishing, for example, has seen any number of innovative ideas that for one reason or another failed to thrive. Failure does not necessarily reflect poorly on the creator—sometimes, it’s just not steam engine time. Take, for example, these five bold ventures…

Twayne Triplets

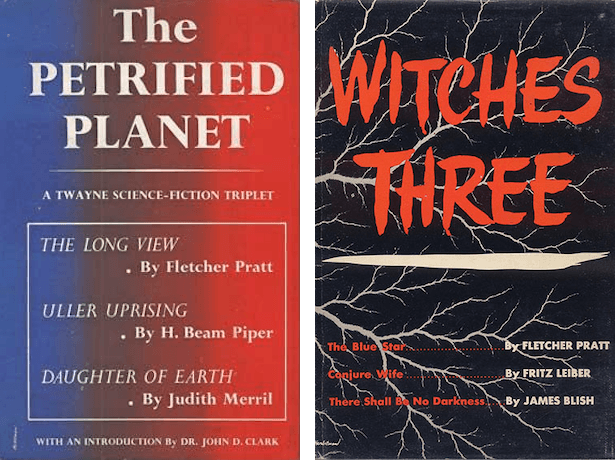

The idea behind the Twayne Triplets was straightforward: A scientist would write a non-fiction article outlining an SF setting, then three SF author would write stories based on that setting. The first volume, The Petrified Planet (1952), contained an essay by John D. Clark, as well as Fletcher Pratt’s The Long View, H. Beam Piper’s Uller Uprising, and Judith Merril’s Daughters of Earth. The second volume, Witches Three (1952), offered non-fiction by John Ciardi (yes, that John Ciardi), and three short reprints not based on the essay: Fritz’ Leiber’s classic Conjure Wife, James Blish’s “There Shall Be No Darkness,” and The Blue Star by Fletcher Pratt.

Details on what would have been the third volume are difficult to track down, but I do know that one of the stories would have been Poul Anderson’s Planet of No Return, and another Asimov’s Sucker Bait, both set on a habitable world in a Trojan orbit around twin stars. The author of the third piece appears not to have finished it. In any case, the third volume never saw print. That was that for the Twayne Triplets.

Which isn’t to say the essential seed—a collection of prose authors writing in a shared setting—didn’t survive. Poul Anderson in particular seems to have been taken by it. Anderson and co-editor Roger Elwood presented their own version in 1977’s A World Named Cleopatra. Cleopatra seems to have made few ripples, but in 1979 Anderson was one of the authors recruited for Robert Asprin and Lynn Abbey’s Thieves World shared-world anthology. Thieves World was not merely successful; it was followed by many sequels. A host of shared-world anthologies by a variety of authors followed.

Continuum Anthologies

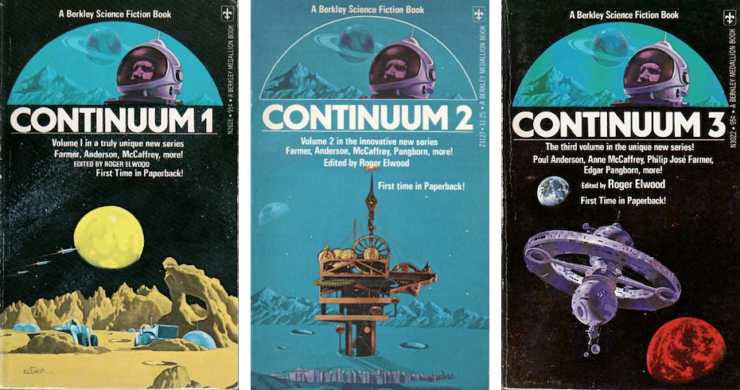

Speaking of Roger Elwood and not entirely successful experiments—no, not Laser Books!—among the myriad anthologies with which Elwood flooded SF in the mid-1970s was a themed quartet of Continuum anthologies, unsurprisingly titled Continuum 1 (1974), Continuum 2 (1974), Continuum 3 (1974), and Continuum 4 (1975). Continuum’s theme was continuity. Each of the four volumes had one story each by Philip José Farmer, Poul Anderson, Chad Oliver, Thomas N. Scortia, Anne McCaffrey, Gene Wolfe, Edgar Pangborn, and Dean R. Koontz. Each author’s four stories shared the same setting.

There are a number of reasons why Continuum is obscure. The anthologies are old. The conceit was interesting but most of the stories were unmemorable. Elwood’s spate of unsuccessful anthologies might have poisoned the well for any ideas associated with him. On the other hand, Continuum at least delivered what it promised.

Combat SF edited by Gordon R. Dickson (1975)

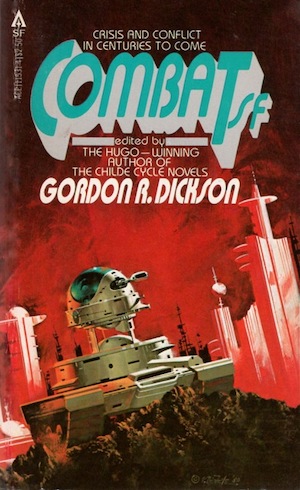

Readers these days are familiar with the basic concept of military science fiction. Works that would now be classified as MilSF date back to the early days of the genre. However, it is widely agreed amongst the writer of this essay that the idea of military SF as a specific subgenre with its own well-defined conventions didn’t really gel until the 1980s. For example, the frequency of the terms “military science fiction” and “military SF” suggest few people were discussing that sort of story using those particular terms before the 1980s.

Combat SF’s unifying theme was combat…the title is something of a giveaway. Dickson rather self-consciously justifies his theme in the introductory essay, then provides a selection of proto-MilSF stories published over the previous decade from such authors as Laumer, Drake, and Joe Haldeman. In the context of the anthology-happy 1970s, it was just another themed anthology, long since out of print. In a larger context, it hints at coming changes in the SF zeitgeist.

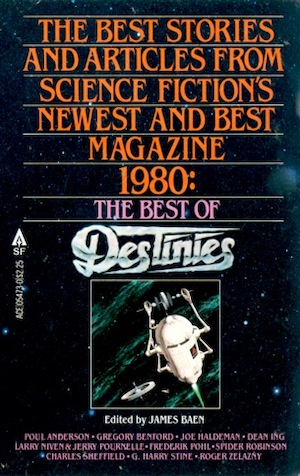

Destinies 1–11, edited by James Patrick Baen

Jim Baen edited If in 1974 and Galaxy from 1974 to 1977. After moving from the financially troubled—well, clearly doomed, if we’re being honest—Galaxy to Ace Books in 1977, he seems to have missed magazine editing, if Destinies is any guide. Destinies is a magazine in mass market paperback form, providing a dose of short science fiction and ostensibly non-fiction essays once every two months (later, quarterly).

Between the first issue in 1978 and the final issue in 1981, Destinies generated eleven issues, as well as 1980’s The Best of Destinies and an ancillary anthology, Richard S. McEnroe’s 1981’s Proteus, which drew on material acquired for Destinies and later deemed unsuitable for it. Baen moved on to Tor Books before founding his own publishing house. I have very fond memories of Destinies, memories which I plan to imperil by gradually rereading the lot.

Destinies did not long survive its editor’s exit from Ace. Baen seems to have thought the essential idea had potential, launching the Far Frontiers bookazine in 1985, and New Destinies in 1987. Neither lasted long: seven issues for Far Frontiers, and ten for New Destinies. There’s nothing obviously wrong with the format so I am a bit puzzled why the later series were so short-lived.

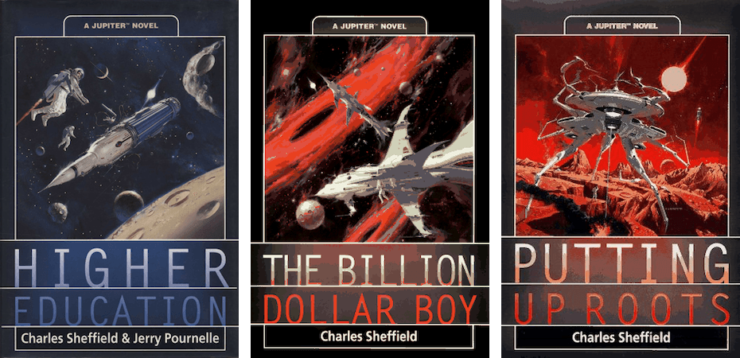

Tor’s Jupiter novels were comprised of Higher Education (1995) by Charles Sheffield and Jerry Pournelle, The Billion Dollar Boy (1997) by Charles Sheffield, Putting Up Roots (1997) by Charles Sheffield, The Cyborg from Earth (1998) by Charles Sheffield, Starswarm (1999) by Jerry Pournelle, and Outward Bound (1999) by James P. Hogan. The intention was to deliver to to the kids of the 1990s the same sort of young adult books Robert Heinlein delivered forty years earlier, thus ensuring there would be another generation of keen SF readers.

I feel utter dread and foreboding whenever an author announces their intention to emulate Heinlein. This series helped develop that conditioned reflex. The books are not so much terrible as remarkably unremarkable, hemmed in by the model they’re trying to emulate. The fact that they did have a model may have worked against them. Upon rereading the Heinlein juveniles, it became clear to me that Heinlein was experimenting with the juvenile form as he went along. The Jupiter novels, on the other hand, feel as constrained by editorial convention as any Laser or old time Harlequin Romance novel.

Still, as the recent explosion in young adult fiction shows, the essential idea behind the books was sound. Young people do want to read fantastic fiction. They just aren’t especially keen on reading the same sort of fantastic fiction their grandparents read, any more than kids in the 1950s wanted to read Tom Swift or Don Sturdy novels.

***

Perhaps you have your own favourite obscure but noteworthy experiments like the ones above. Feel free to mention them in the comments below.

In the words of Wikipedia editor TexasAndroid, prolific book reviewer and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll is of “questionable notability.” His work has appeared in Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews and the Aurora finalist Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis). He is a four-time finalist for the Best Fan Writer Hugo Award, is eligible to be nominated again this year, and is surprisingly flammable.