We must begin this arotake pukapuka (book review) by talking about reo (language)—which means we need to talk about history and power. As a reader of this blog, you are most likely not a New Zealander, and are probably primarily familiar with our country through The Lord of the Rings films. It’s a start: you have at least seen some of our extraordinary landscapes. But long before they were used to tell that foreign tale this land has been layered with Indigenous stories that stretch centuries into the past and are continuing into the present and future.

A recent high point in such storytelling is the new pakimaero (novel) Kurangaituku by Whiti Hereaka, who comes from Ngāti Tūwharetoa and Te Arawa tribes.

Kurangaituku is written mostly in English with a liberal sprinkling of Māori words and phrases. A lot of our kaituhi Māori (Māori—i.e. Indigenous—writers) write in English. This is because part of the violent settler-colonial project of turning Aotearoa into New Zealand was to suppress te reo Māori (the Māori language). Schoolchildren were beaten for using it in class and grew up to encourage their own children to speak English in order to get ahead in the new world. As a result, many Māori are no longer able to speak—or write in—their own language.

Buy the Book

Kurangaituku

Hereaka herself is learning te reo as an adult (NB: ‘te reo’ literally means ‘the language’ but is used colloquially to mean the Māori language). At a recent Verb Wellington literary festival event celebrating Kurangaituku she said: “I found the space in my mouth where te reo lives”. So her use of te reo in this pukapuka (book) is important and hard-won. I’m glossing my own use of te reo as we go in this arotake (review) but Hereaka rightly does not do so in her pukapuka. Instead, you can pick up the meanings from context clues, or, if you’re curious, use the free online Māori-English dictionary Te Aka.

Let’s start with how to pronounce Kurangaituku, the name of the protagonist of our tale. It’s a gorgeously long kupu (word) and worth taking your time over. Ku–rung–ai–tu–ku. You can hear Hereaka saying it and reading an excerpt from her pukapuka in this video. She starts by saying “This is from what is physically the middle of the book, technically the end of the book, but where most of us began—the story of Hatupatu and the Bird-Woman.” So too, in the middle of this arotake pukapuka (book review), we have finally found our way to the beginning of the story.

Hatupatu and the Bird-Woman is a famous pūrākau (myth) in te ao Māori (Māori society). In most tellings, Kurangaituku is a monster—half bird, half woman. She captures Hatupatu but he uses his cunning and daring to escape, stealing all her treasures as he does so. Kurangaituku is Hereaka’s retelling of the pūrākau from the bird-woman’s point of view.

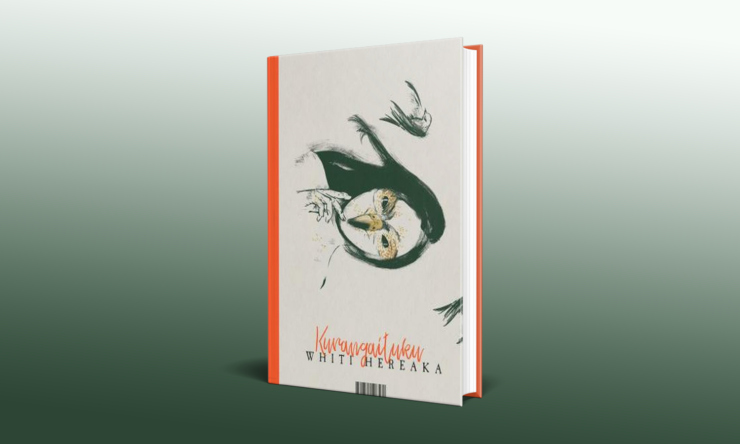

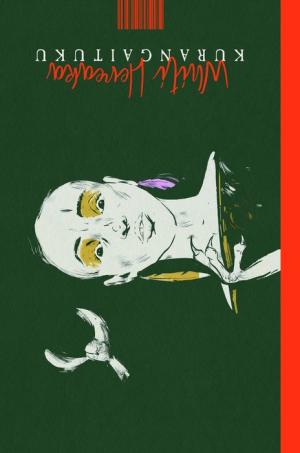

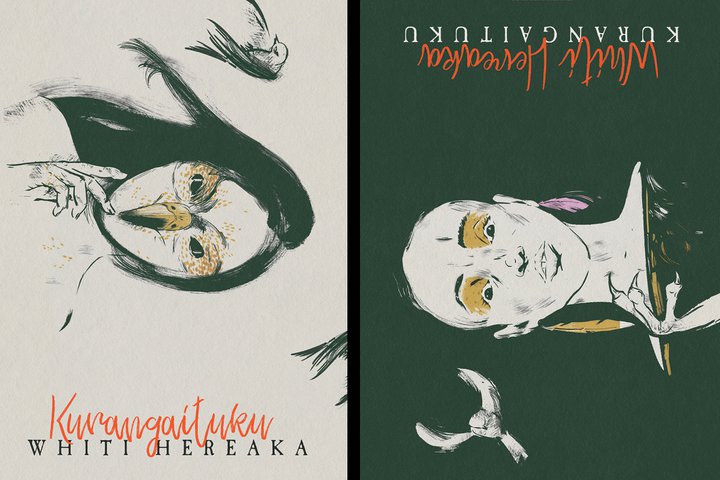

It might be tricky, since you’ll have to ship it from Aotearoa New Zealand, but if at all possible I recommend getting your hands on Kurangaituku in paperback. (It is available in ebook too.) This is because it has been created as a physical storytelling experience. There are two front covers, both of which bear an image of Kurangaituku. In one cover, with a black background, she is shown with a mostly human face and a bird claw hand. In the other, with a white background, she has a more birdy-looking face (including beak) and a human hand. You pick one cover and start reading into the middle of the pukapuka, then flip it over and read again from the other side. Towards the middle the two story-directions are woven together, so you’re reading every second page while the intermediate pages are upside down. Kurangaituku is the point-of-view character throughout. (How this works in the ebook edition is that the reader chooses a bird as their guide—either miromiro or ruru—and reads through one story-direction, then is presented with a link to begin the other one.)

I started reading from the white-background end, where the story starts at the beginning of all things in Te Kore, the void that exists before the universe. Te Kore becomes Te Pō, the darkness, and then Te Whaiao, daylight. “Beginning. Middle. End. Middle. Beginning.” Kurangaituku sometimes addresses the kaipānui (reader) directly: “You too are a curious creature, hungry for experience–I recognise myself in you…I have borrowed your voice; I am clothed in your accent”. We are with Kurangaituku as she wills herself into being and travels through time, space, and realities. As the pukapuka progresses we meet not just Hatupatu and his brothers in te ao mārama (the physical realm) but a whole range of atua (supernatural beings) in Rarohenga (the spirit world). At first Kurangaituku is created by the birds in the form of a giant kōtuku (white heron), but when the Song Makers (i.e. humans) come along they use language to recreate her partly in their own image. Thus she becomes part bird, part woman. The power of language and storytelling to shape reality is a repeated theme.

The narrative structure feels weird but it really works. Making the reader physically turn the pukapuka (book) around and start again reinforces the idea of Kurangaituku as the latest retelling of an old, old story. At the Verb Wellington event Hereaka said “I reject the idea of originality … it’s important for the health of our pūrākau [myths] to keep retelling them”. Hereaka also demonstrated this kaupapa (guiding principle) when she co-edited with Witi Ihimaera the 2019 anthology Pūrākau: Māori Myths Retold by Māori Writers, which I also highly recommend. In their introduction to this anthology, Hereaka and Ihimaera write that pūrākau “may be fabulous and fantastic but they are also real… Nor is there any separation of the ‘fanciful’ stories of our origin, i.e mythology and folklore, from the believable or factual… Māori do not make those distinctions. It’s all history, fluid, holistic, inclusive–not necessarily linear–and it may be being told backwards”.

One of the functions of the interwoven story-directions of Kurangaituku, then, is to invite the reader to accept that this story is both made-up and true at the same time. It turns upside down your ideas of what a pakimaero (novel) is; what speculative fiction is; what magic realism is. At the Verb Wellington event Hereaka said: “I don’t believe magic realism is a thing, it’s just the Indigenous way of looking at things”.

Hereaka also spoke about how she was nervous to find out how Māori would receive her new retelling of the pūrākau (myth). In my reading, as a Pākehā (white New Zealander), I could feel the weight of history and expectation in her sentences but they are strong enough to bear it, woven tightly and expertly together to create a real work of art. Kurangaituku is serious in its depth and thoughtfulness but never pompous—in fact, as well as being engaging it is also sometimes very funny; a real page-turner in the most literal possible sense. It feels both solid and uncanny in a very powerful way.

I got chills when, partway through the pukapuka, Kurangaituku says: “I have ceased to be the words on this page and have become a real being, making her nest in your brain.” Building on the mahi (work) of the Song Makers before her, Hereaka is now using the power of not one but two languages to reshape Kurangaituku once more. Long may they both continue.

Kurangaituku is published by Huia.

My ancestors come from England

I am here in Aotearoa New Zealand by virtue of the Treaty of Waitangi

I was born in Auckland in the traditional tribal area of the Ngāti Whātua tribe

Waitematā Harbour is the body of water that is special to me

Mount Albert is the mountain that is special to me

I now live in Wellington in the traditional tribal area of the Te Āti Awa tribe

My name is Elizabeth Heritage