March 2012 has been a tragic month for science fictions fans. First we saw the passing of Star Wars artist Ralph McQuarrie, followed closely by the passing of French comic book and SF movie visionary Jean ‘Moebius’ Giraud. And as if both were not painful enough, last week saw news that anime legend Noboru Ishiguro had also died at the age of 74.

Ishiguro may not sound familiar to US science fiction fans, but like Moebius he’s another figure whose influence extends further than his name. There are few people in anime history — especially within science fiction anime — who worked on so many landmark series and franchises. And he started early too — in 1963, while still a student, he got his first work as an animator on Tetsujin 28-go, arguably the first giant robot anime series. A massive hit in Japan, it is the story of Shotaro, a young boy who takes control of the eponymous robot built by his late father to fight crime and invading enemy robots. A year after Ishiguro joined the already long-running production, Tetsujin 28-go was one of the first anime series to receive a U.S. translation and TV broadcast in the form of Gigantor, fueling an early interest amongst American SF fans in Japanese animation.

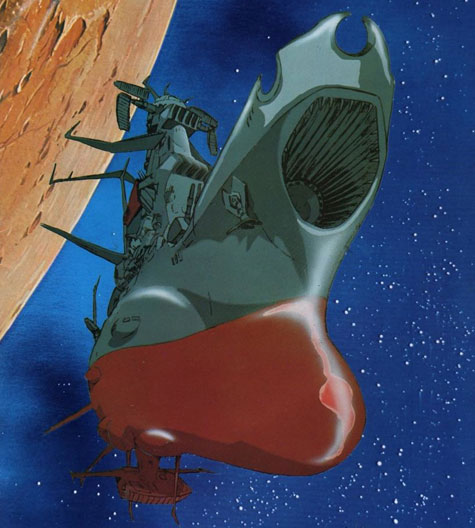

However it wasn’t for another decade that Ishiguro would take the helm of a major series. In 1974 he helped create and directed Space Battleship Yamato, a TV show destined to become an undeniable anime classic. Earth is under attack from mysterious aliens, who have left the planet’s surface uninhabitable by bombarding it with a rain of radioactive meteorites, forcing the survivors of the human race to retreat underground. The attack has been so damaging that scientists predict the Earth only has a year until the effects are irreversible, and a desperate last-ditch mission is launched to find a legendary device that can remove the destructive radioactivity. A spaceship is built from the wreckage of the real-life Japanese battleship Yamato — sunk by the U.S. Navy in 1945 — and over several series, and both live action and animated movies, Space Battleship Yamato followed the adventures of it’s crew as they tried to save Earth from its fate.

With its themes of radioactive attack and lost battleships it’s easy to see how Yamato tapped into the consciousness of a Japan still aware of it’s defeat in World War II, and it was certainly a key part — along with it’s distinctive character designs and gritty, almost grungy art style — of it’s massive popularity in its home country. But again Yamato would also propel Ishiguro’s work across the pacific to a U.S. audience, when the show was re-dubbed as Star Blazers. As the first popular Japanese series shown in the U.S. that had an over-arching plot that required the episodes to be shown in order, and a more mature storyline following developed characters and their relationships, Star Blazers’ broadcast in 1979 is credited by many today as the show that gave birth to American anime fandom. Certainly it was different enough from U.S. cartoons of the time and, launched in the same year that Star Wars was redefining box office records, it became both a Saturday morning hit and cult fan favorite.

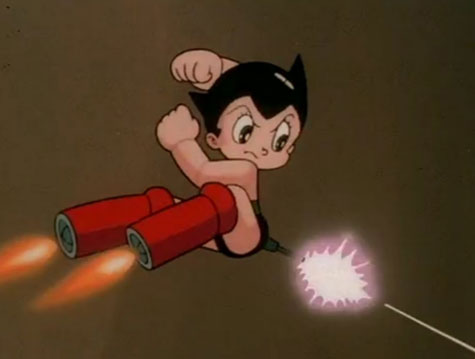

Yamato’s success in Japan was to push Ishiguro’s career even further, landing him the job of remaking Astro Boy — one of Japan’s most beloved and treasured franchises — for the TV in 1980. Based on ‘God of Manga’ Osamu Tezuka’s iconic characters it must have seemed like a formidable task — Astro Boy had been made for TV before, in 1963, and was considered by many the show that cemented anime’s look and style. It’s impossible to measure Astro Boy’s cultural significance in Japan — he is as identifiable a figure as Mickey Mouse, Superman and R2-D2 rolled into one — but none of this seemed to faze Ishiguro from delivering another TV hit. His version of Astro Boy would not only be the first animated depiction of the iconic robot in color, but he would give the story a slightly more mature and dark edge, arguably taking it closer to the spirit of Tezuka’s original manga than the proceeding TV adaptation. Again, the show would go on to be not just a hit in Japan, but also to be broadcast in the U.S. and around the globe.

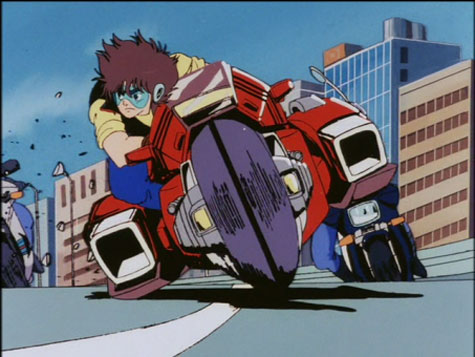

52 episodes of Astro Boy and 2 years later and Ishigoru would be directing another landmark show — Super Dimension Fortress Macross. Again a story of Earth facing up to a powerful alien invasion, this time it’s a reverse-engineered alien battleship that gives the show it’s title and becomes mankind’s last hope. Macross’ combination of battling mecha and likable but complex characters in ever-evolving relationships would guarantee it would become a massive hit in Japan — spawning literally decades of Gundam style spin-offs and adaptations — but it was yet another Ishigoru helmed work that saw huge success when exported to the U.S..

In 1984 the late Carl Macek — who would go on to found U.S. anime distribution and dub company Streamline — unleashed Robotech on unsuspecting American audiences. Built largely from footage from Macross (although it also took from a couple of other series; Super Dimension Cavalry Southern Cross and Genesis Climber Mospeada), Robotech was a huge hit stateside, and almost single-handedly introduced Japanese style mecha armored suits, and in particular thrilled kids with it’s transforming jet fighters a number of years before Transformers hit the U.S.. Notably tabletop war-game company FASA ‘borrowed’ many Robotech/Macross mech designs for it’s famous and influential Battletech and Mechwarrior games, leading to years of legal action and controversy that would ultimately sink the company. Up until his death in 2010 Carl Macek would remain a controversial figure amongst anime fans, with some of them accusing him of ‘butchering’ Macross with his story re-writes and character re-naming, but arguably he did what needed to be done at the time in order to sell the series — and the medium — to Western audiences. At the very least, the continuing controversy showed that Robotech had helped give birth to a passionate, knowledgable movement of American anime fans willing to dig out and enjoy original and untampered Japanese works.

The later half of the 80s would see Ishiguro go on to be a significant figure in SF anime, including his direction of the cyberpunk OVA Megazone 23 in 1985. Allowing Ishiguro to take his sometimes darker edged themes beyond epic space opera, Megazone 23 is a clearly more mature and violent title heavily influenced by Blade Runner, Moebius and early Japanese cyberpunk manga. Again, it would go on to have a significant cult following in the U.S. and U.K. as part of the anime home video boom lead by Akira — with which it has notable similarities — in the early 1990s.

But Ishiguro would return once more to space opera, with what would be perhaps his greatest artistic achievement — Legend of The Galactic Heroes. I wrote about it for Tor earlier this year, and to paraphrase that post “based on a series of SF novels by Yoshiki Tanaka, Legend of the Galactic Heroes‘ long adaption to animated form started in 1988, and soon became considered the pinnacle of anime’s military SF storytelling. Depicting the interstellar human civilization of the 35th century, it tells the story of two warring factions through the eyes of two young, enigmatic commanders…the true reason for the epically long series popularity amongst fans is that its elegant and non-stop story-telling is utterly enthralling. One minute you are watching massive space battles between fleets of thousands of fantastically designed ships, the next war-room clashes or conspiratorial political dealings. All are as engaging as each other.’

Ishiguro directed well over 100 episodes of the show, as well as an OVA and two movies — displaying an obvious passion for what is a truly landmark series in anime history. In amongst the fantastic storytelling and subtle direction it also displays (along with Macross) another of his loves — Ishiguro was also a talented musician, and his love of music is displayed in how LoGH’s epic space battles are lovingly choreographed to classical music.

Although he never had another hit that quite lived up to LoGH, Ishiguro’s studio Artland would produce shows like the critically acclaimed Mushishi and Tytania — the later directed by the man himself in 2008 and based again on a series of Yoshiki Tanaka’s SF novels. But perhaps most telling, it was during this period that Ishiguro started to visit the U.S., becoming a relatively frequent guest at anime conventions up and down the country, as if in later life looking back and enjoying what his career had meant to so many fans across the world. It means he will be sorely missed by SF fans outside Japan not just as an incredibly talented creator, but also as a recognizable face, personality, and ambassador for anime.

When he’s not writing for Tor.com, Tim Maughan writes science fiction—his critically acclaimed book Paintwork is out now, and has been picking up support from the likes of Cory Doctorow and Ken MacLeod. So you should probably go buy it already.