Tor.com comics blogger Tim Callahan has dedicated the next twelve months to a reread of all of the major Alan Moore comics (and plenty of minor ones as well). Each week he will provide commentary on what he’s been reading. Welcome to the 24nd installment.

“Marvelman” and “V for Vendetta” were nearing the last pieces of their runs in Warrior magazine. The fallout from “The Anatomy Lesson” was rumbling through The Saga of the Swamp Thing. Captain Britain was involved with something massive, I’m sure, omniversally-speaking.

We’re talking July, 1984, or so the cover-date of 2000 AD prog 376 would have us believe.

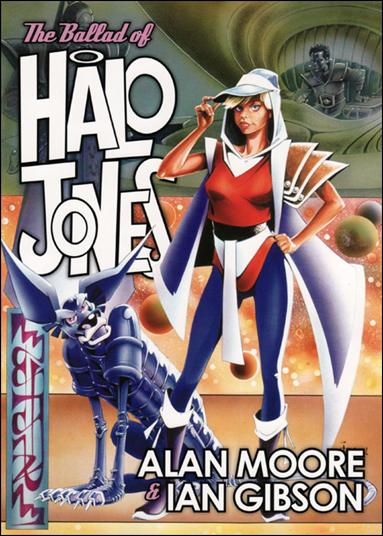

That’s when Alan Moore and Ian Gibson launched a bold new series in the pages of that sci-fi boys adventure magazine. A recurring five-pager called “The Ballad of Halo Jones.”

This was no gun-toting super-cyborg, or a lethal assassin from a world she never made. Instead, Moore and Gibson conceived of a strip that was quantifiably antithetical to the ethos of 2000 AD at the time. This would be a series about a young woman growing up, perhaps caught up in extraordinary affairs, but not heroically. And she would spend significant time shopping.

Of course, Moore and Gibson set their series dozens of centuries in the future and created a high-tech tableau for their story and plenty of social commentary woven throughout.

But it was still, at its core, the story of a young woman, dancing with dignitaries, living her life.

The series was popular enough with readers to warrant a return for “Book Two” the following year, with “Book Three” wrapping up in 1986. There was some talk, early on, of nine books total, bringing Halo Jones from the cusp of adulthood in the beginning to old age in the finale. But rights disputes with the folks behind 2000 AD led Moore to walk away from the character forever. Ian Gibson would still be interested in doing more Halo Jones. Perhaps DC could scoop up the rights and put Darwyn Cooke on the case.

“The Ballad of Halo Jones,” though and I teased this in the comments of The Great Alan Moore Reread a couple of weeks ago is far from my favorite Alan Moore work. I’d rank it near the bottom, actually. It’s certainly the worst of this mid-1980s golden era of Moore, even though it does have some fleeting charm. But as a whole, the three extant books of “Halo Jones” suffer more than they succeed. I’d love to see defenders of the series advocate for it in this week’s comments. I’d like to hear some counter-arguments. What do people actually like about “Halo Jones”?

Because for me, it’s Alan Moore’s version of a futuristic female Forrest Gump. And just because he wrote the series a decade before that abominable film (and a year or two before the release of the novel upon which it was based) he still should have known better.

The Ballad of Halo Jones (Rebellion, 2010)

As far as I know, all the collected editions of the “Halo Jones” strips are all basically the same, but not exactly you get all three books of “The Ballad of Halo Jones” and maybe a couple of sketches or covers. At least one version includes an introduction by Alan Moore. This one doesn’t. So what we’re left with, via Rebellion circa 2010, is a group of stories from 1984-1986 that must stand on their own. A saga of a young woman growing up and living and loving and suffering and overcoming and well the problems begin in the opening few chapters.

Ian Gibson’s plastic figures aren’t helpful Gibson’s characters have two expressions: pouty and emotionally pouty but he’s a slick enough artist to keep the story moving along coherently and imply a larger world (and universe) than we’re ever fully shown.

So the art’s not the biggest concern, even though most of the usual 2000 AD crop of pencilhacks would have probably been able to pull more pathos out of the situations presented here.

No, the problem is Alan Moore’s grasping at Douglas Adams absurdity and continually falling short, then shifting into biting social commentary like, say Anthony Burgess, before ultimately settling into some combination of the two mixed with a heavy dose of soap opera melodrama. I don’t know what was on the BBC in those days, but “Halo Jones” feels dipped in bathetic hyperdrama in what I would term for contemporary audiences along these lines: imagine Beverly Hills 90210 with clumsy futurespeak, by the writers of Chuck, and the set director for Caprica.

That’s just nonsense, I realize, like saying that “Halo Jones” is a meal of yogurt and escargot and lemon mustard, but that’s because the series feels not just discordant, but endlessly familiar in its pieces yet completely unworkable as a whole. Like an engine made out of jello and inner tubes.

(I could spend the rest of this post just listing other random nouns that don’t go together. To avoid that, I will move on and assume you now get the sense of what it’s like to read “The Ballad of Halo Jones,” even as I go on to write more about some of its details.)

The main joke on the opening two page spread is an example of the kind of trying-and-failing I’m talking about. Swifty Frisko broadcaster, and most minor of minor characters announces the promotion of a Procurator Fiscal, and a related name-change: “Mr. Bandaged Ice That Stampedes Inexpensively Through a Scribbled Morning has added another three words to his name he will now be addressed as ‘Procurator Bandaged Ice That Stampedes Inexpensively Through a Scribbled Morning Waving Necessary Ankles’…Crazy name for a crazy reptile!”

You can feel the tiny Douglas Adams trying to crawl out of Alan Moore’s beard, right?

That tonality would be fine, honestly, if the story did more than just sprinkle in the overbearing absurdity amidst the cultural chatter. But there’s a distinct lack of substance in the main characters, particularly in Book One, and Halo Jones is an incredibly uninteresting protagonist.

I get that Alan Moore was reaching for something different and ambitious: an inaction non-hero in an otherwise ultra-violent anthology comic. Halo Jones, though, can’t carry the weight of the plot. She’s presented as a kind of everygirl, stumbling through incidences, practically with no distinctive personality of her own. Yet she’s the one we’re forced to follow, for page after page, as if making her “normal” in a world full of craziness is somehow a reason to keep reading. It’s not, and for the first time in this entire Great Alan Moore Reread, I faced a comic that I would have put back on the shelf halfway through if not for my own sense of duty to actually read all these pages even if I barely write about any of them.

But I persevered. And since that seems to be the moral of “The Ballad of Halo Jones” by the end something about there being more to life, so don’t give up maybe Alan Moore knew what he was doing all along.

Back to the story that is barely worth reading!

The short version: Halo Jones hangs out with her pals, goes shopping, gets into some minor scrapes, and finds her friend murdered by an unknown assailant, and then moves away. And that’s basically all of Book One. Passive Halo Jones, going from one incident to the next, like a certain maudlin Tom Hanks character from a bafflingly-beloved movie.

Also: “Ice Ten” is the name of a musical group in the comic. That’s a hilarious Kurt Vonnegut joke, maybe. (The “maybe” refers to the level of hilariousness, not that it isn’t a Vonnegut reference, because it clearly is. Still, “Ice Ten”? That’s the level of humor in here?)

(I’ll also note that a particularly annoying feature of reading “The Ballad of Halo Jones” in a collected edition, because it’s a series of five-page installments, originally designed to be read with a week in between chapters, the characters constantly repeat each other’s names. Again and again. I don’t remember that being a problem with “Skizz,” but here it’s an unbearable tic.)

In Book Two we learn that Brinna, Halo’s murdered friend, was actually killed by her own robodog. And we get a high-octane confrontation when Halo learns the truth and someone else comes in to save her. Because she’s Halo Jones, and we can’t have her doing anything that might make her seem the least bit worth reading about.

Actually, I should hold back a bit on my mockery, because Book Two is far more entertaining than the other two books of the Ballad, with a couple of subplots that swerve in just the right off-kilter way, like the mystery of the mostly-ignored child called Glyph and the strange secret of the Rat King. The opening chapter of Book Two is the strongest single chapter of the entire saga, actually, mostly because it’s completely about the character of Halo Jones without her ever appearing to suck the life out of the pages. Instead, she’s the object of academic perfection from a future-history point of view. And though that rose-colored lens she’s far more of a vital force then she is when she’s actually starring in her own series.

Book Three nods toward making Halo a viable lead in an action series by throwing the sci-fi trope of the future-soldier into the tale. What we get is kind of a proto-Martha-Washington-Goes-to-War, or Alan Moore’s twist on the Joe Haldeman kind of Vietnam-in-space novels. Halo, now a whole lot more grizzled, becomes a gun-toting lead for the first time, and yet, to stay true to the premise of the series, she constantly struggles against her own compulsion towards violence.

Let me put it this way: in Books One and Two, Halo Jones is a mostly passive character who has things happen to her. In Book Three, she becomes the agent of her own destiny, but still spends too many pages making “ugh” faces at blaster rifles and throwing down her military garb and saying things like, “No!! What’s happening to me? I’m going crazy, and I’ve got to get out of here ” before returning to a new battle like a mannequin posed for action that will never happen.

Ian Gibson also throws in an absurdly muscled Rambo caricature in Book Three that may or may not have been specifically called for in the script. (I’m leaning towards, “yes, I’m sure it was.”) I suppose that’s a funny allusion in 1986. Jim Abrahams and Charlie Sheen teamed up to make it hilarious as recently as 1993.

When a series falls short of even Hot Shots! Part Deux, there’s a problem, even when Alan Moore’s name is on the cover.

This comic is just so completely Alan Moore’s Forrest Gump from beginning to end, with Halo sleepwalking and stumbling and kind-of-trying-but-feebly through events. I don’t know what else to say, except: “if you haven’t read The Ballad of Halo Jones after all these years, feel free to skip it. The rest of your life will thank you.”

NEXT TIME: Perhaps More Worthwhile Stories from Alan Moore This Time in Gotham City!

Tim Callahan writes about comics for Tor.com, Comic Book Resources, and Back Issue magazine. Follow him on Twitter.