Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches.

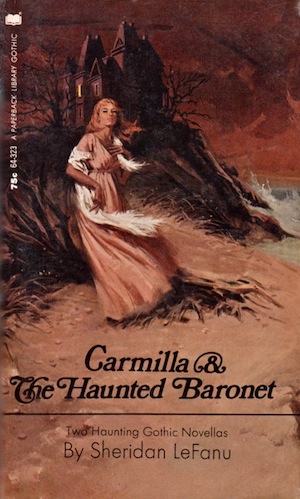

This week, we continue with J. Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla, first published as a serial in The Dark Blue from 1871 to 1872, with Chapters 9-10. Spoilers ahead!

“…you believe in nothing but what consists with your own prejudices and illusions. I remember when I was like you, but I have learned better.”

The night after Carmilla’s “sleep walking” episode, Laura’s father posts a servant outside her room to make sure she doesn’t somnambulize again. The dark hours pass without incident. Next morning, without telling Laura, her father summons the local physician. Dr. Spielsberg listens to her story in the library, his face growing graver as the narrative progresses. As she concludes, he gazes at her “with an interest in which was a dash of horror.”

Spielsberg and Laura’s father have “an earnest and argumentative conversation” in a recess beyond Laura’s hearing. Laura, who has felt very weak but not otherwise ill, begins to grow alarmed when the doctor examines the place below her throat where she dreamed that two needles pierced her. Her father pales at whatever they see; the doctor reassures her that it’s only “a small blue spot, about the size of the tip of your little finger.” Is this spot where she senses strangulation and a chill like the flow of a cold stream? Receiving her confirmation, he calls Madame Perrodon back to the library. Laura is “far from well,” he says, but he hopes she’ll recover completely after certain necessary steps are taken. Meanwhile, he has one direction only: Perrodon must see to it that Laura isn’t alone for one moment.

Laura’s father asks Spielsberg to return that evening to see Carmilla, who has symptoms like Laura’s but much milder. Afterwards Perrodon speculates the doctor might fear dangerous seizures. Laura thinks the constant companion is required to keep her from doing some foolish thing to which young people are prone, like, oh, eating unripe fruit.

A letter arrives from General Spielsdorf to announce his imminent arrival. Normally Laura’s father would be delighted over his friend’s visit, but now he wishes the General could have chosen another time, when Laura was “perfectly well.” Laura implores him to tell her what Spielsberg thinks is wrong. He puts her off. She’ll know all about it in a day or two; until then she mustn’t “trouble [her] head about it.”

Her father wants to visit a priest near Karnstein, and he invites Laura and Perrodon to accompany him and picnic at the ruined castle. As Carmilla’s never seen the ruins, she’ll follow later with Mademoiselle La Fontaine. They drive west through beautiful wooded and wild country. Around a bend they suddenly meet General Spielsdorf. He agrees to accompany them to the ruins while his servants take his horses and luggage to their schloss.

In the ten months since Laura and her father last saw Spielsdorf, he’s aged years, grown thin, and lost his usual appearance of “cordial serenity” to a pall of “gloom and anxiety.” This is understandable given the death of his beloved niece Bertha, yet his eyes gleam with “a sterner light” than grief normally induces. “Angrier passions” seem to be behind it, and indeed he soon breaks into a bitter and furious tirade about “the hellish arts” that beset Bertha. He would tell his old friend all, but Laura’s father is a rationalist. Once the General was like him, but he’s learned better!

“Try me,” says Laura’s father. He’s not as dogmatic as once he was, himself.

“Extraordinary evidence” has led the General to the belief that he’s been “made the dupe of a preternatural conspiracy.” He doesn’t see his friend’s dubious look, for he’s staring gloomily into the woods. It’s a lucky coincidence, he says, that they’re bound for the ruins—he has “a special object” in exploring the chapel there and the tombs of the extinct family.

Buy the Book

And Then I Woke Up

Laura’s father jokes that the General must hope to claim the Karnstein title and estates. Instead of laughing, the General looks fiercer than before, and horrified. Far from it, he says. He rather means to “unearth some of those fine people” and “accomplish a pious sacrilege” that will eliminate certain monsters and enable honest folk to sleep unmolested in their beds.

Now Laura’s father looks at the General with alarm rather than doubt. He remarks that his wife was a maternal descendant of the Karnsteins. The General has heard much about the Karnsteins since they last met, when his friend saw how lovely and blooming Bertha was. That’s all gone now, but with God’s help he’ll bring “the vengeance of Heaven upon the fiends who have murdered [his] poor child!”

Let the General tell his story from the beginning, Laura’s father says, for “it is not mere curiosity that prompts [him].”

And as they travel on toward the ruins, the General opens “one of the strangest narratives [Laura] ever heard.”

This Week’s Metrics

By These Signs Shall You Know Her: Vampiric attacks are extremely diagnosable by a small blue spot at the bite location. If the bite is shaped like a bulls-eye, on the other hand, that’s not a vampire but a tick.

What’s Cyclopean: The General expresses, with exasperation, “his wonder that Heaven should tolerate so monstrous an indulgence of the lusts and malignity of hell.”

Madness Takes Its Toll: Laura’s father may trust the General’s evidence-based judgment, but comments about preternatural conspiracies are enough to elicit “a marked suspicion of his sanity.”

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Rebecca Solnit has an excellent essay collection called Men Explain Things to Me. I kept thinking of that this week, because it’s possible to err too far in the other direction: Laura could really use at least one man telling her what the hell is going on. Admittedly, good medical communication is inimical to good story pacing. And utter disinterest in being honest with women about their illnesses is unfortunately realistic for the time. Nevertheless, “something is attacking you at night” is simple to say, and more useful than insisting on an uninformed and potentially-easily-intimidated (or enthralled) chaperone.

I realize that the general is literally about to explain everything in the next chapter, and that he’ll do a better job than Daddy or the stodgy-yet-vampirically-informed doctor possibly could. Mostly I’m just annoyed that we’ve managed to end up with a two-chapter segment in which the entire plot development is that there might soon be a plot development.

Then again, as I think about it, these may honestly be the two most horrific chapters in the whole of Carmilla. Bad things will happen to us all: fundamentally, we know this. At some point in our lives we’ll get sick, and some of those illnesses might be dangerous or debilitating or even deadly. We’ll lose people and things that we care about deeply. Opportunities pass and sometimes they never appear again. Sometimes even simple pleasures, like going out to eat, vanish between one day and the next and you find yourself overcome with regret by the fragile and changeable nature of existence.

But what’s both true and distressingly unnecessary is that people will lie to us about all the above horrors. And in doing so, they’ll make the horror worse: avoidable dangers less avoidable, unavoidable ones isolating and unspeakable. To acknowledge a horror is to permit fear and offer reassurance, and sometimes even to offer tools to fight back. And yet, so often, authorities or society or just people too nervous to deal with the drama refuse that acknowledgment.

This is totally a post about Carmilla, I swear. Cosmic horror bears no resemblance whatsoever to everyday life in the 21st Century.

My point is that at any time in these two chapters, Laura’s doctor or father could have said, “Yes there is real danger here, we are asking someone to stay with you to protect you from a real thing that’s attacking you in the night,” and that would’ve been not only more respectful but more reassuring and more likely to prevent the actual bad thing from happening. “Don’t trouble your head about it” is an excellent way to get people speculating about deadly seizures. And a terrible way to prepare people to fend off vampires posing as cute best friends.

I find myself therefore rather more sympathetic to the General, who may not have been terribly useful in his original letter, but who since appears to have turned his anger and grief towards useful action (as well as rants about hellspawn). And perhaps, even—perhaps next chapter—toward clear communication.

Anne’s Commentary

Practicing medicine in outback Styria has evidently opened Dr. Spielsberg’s mind to possibilities most physicians would reject out of hand. In Chapter IV, he and Laura’s father closeted themselves to discuss the neighborhood plague; Laura hears only the close of their conversation, which at that time means little to her, much to the reader. Father laughs and wonders how a wise man like the doctor could credit the equivalent of “hippogriffs and dragons.” Spielsberg takes no offense, simply remarking that “life and death are mysterious states, and we know little of the resources of either.” He knows enough, however, to hear the history of Laura’s ailment with increasing gravity and even “a dash of horror”; having heard it, he knows enough to take the next step toward a tentative diagnosis of undead predation.

Check the neck. Or thereabouts. Your typical vampire goes straight for the throat, presumably for the jugular vein. Carmilla aims a little lower, preferring the upper breast—an inch or two below the edge of Laura’s collar is where Spielsberg finds the telltale puncture. To the frightened Laura, he describes this as “a small blue spot.” To be less delicate, a hickey. Carmilla’s a bloodsucker with long experience. She battens onto a spot easier to hide than the side or base of the neck. Laura doesn’t need to wear a conspicuously high collar or that common resource of the female victim, a prettily tied or brooch-clasped black velvet ribbon. Le Fanu does honor (or create?) the trope of a victim either unaware of their wound or indifferent to its significance. Another trope can explain this phenomenon: Vampires are adept at mind control, hypnosis, psychic manipulation. Otherwise they’d have to be as uncouth as werewolves and zombies and devour their prey all at once, before it got away.

Vampires can just chow down and done, as Carmilla does with her peasant meals. They’re fast food. Laura, and the General’s niece Bertha before her, are epicurean delights, to be slowly savored. To be loved, even, for love is a consuming passion, literally so for the vampire. That’s this monster’s tragedy: To have the beloved one is to lose her. Carmilla can wax hyper-romantic all she wants, but is it possible for lovers to die together—to “die, sweetly die”—so they may live together? Carmilla herself knows better. Should she fully consummate her desire for Laura, it would make Laura a being like herself, whose love is a “rapture of cruelty.” A not-Laura, in other words.

I wish Le Fanu had named Laura’s dad. She may naturally write of him as “my father” instead of “Mr. Wright” or whatever, especially since her narrative is meant for a person—an unnamed “city lady”—who presumably would know his name. Still, Le Fanu could have slipped it in somewhere, like in a bit of Perrodon or La Fontaine’s dialogue, “oh, my dear Mr. Wright,” or in a bit of General Spieldorf’s, “see here, Wright.” I get tired of calling him “Laura’s father.” I might even like to call him “Bob.” As in, “Bob, what’s your deal letting Carmilla’s ‘mother’ pull such a fast one on you? What’s your deal letting Carmilla dodge all your reasonable concerns? Is it the elderly infatuation some commentators have read into your behavior? Bob, seriously. You’re supposed to be this really smart and worldly guy. Or maybe you’re too worldly sometimes, like when you snort at Doc Spielsberg’s otherworldly notions until it’s almost too late for Laura.”

Okay, Bob, I get it. There are these here narrative conveniences your creator needs to consider. Le Fanu has to get Carmilla into the schloss for an indefinite stay so she has access to Laura. He needs you not to jump too quickly to (the correct) supernatural conclusions. And let’s give Carmilla all due credit for native cleverness and charm enhanced by the unholy length of her existence. You and the General can’t be the only geezers she’s gotten around.

Nor, to be fair, should I expect you to be less of a nineteenth-century paterfamilias and doting papa, as in how you won’t tell Laura what the doctor thinks is her problem. She may have a right to worry her pretty little head about what’s happening to her own body and soul, but you don’t want to scare her, right, Bob? You want to protect her. Maybe to distract her from her troubles. Is that why you invite her along on a jaunt to the Karnstein ruins the very day you’ve received Spielsberg’s shocking diagnosis?

And there’s narrative convenience again. Le Fanu needs to get us to those long-promised ruins at last, and he needs to gather a lot of characters there at once: you, Bob, and Laura, and the General, and a little later, Carmilla. The General’s a particularly critical consideration. He hasn’t yet told the story of Bertha’s strange demise and of his vow to destroy her murderer; we need that story before any big dramatic scene at the ruins. And there has to be a big dramatic scene at the ruins. What else are eerie ruins with ancestral ties to our heroine for?

The biggest structural creak for me is how you, Bob, are so protective of Laura, and yet you actually encourage the General to tell his harrowing tale of loss in her hearing. Why, too, does the General (however overwrought) not withhold the telling until he and you, his old friend, are in private? I’d think he’d worry about the tender sensibilities of the ladies in the carriage.

Never mind, Bob. I’ll forgive some narrative conveniences in order to get to the General’s tale. I’m as eager as you to hear it, so let Chapter XI begin! Um, next time, that is.

Next week, we celebrate National Poetry Month with Amelia Gorman’s Field Guide to Invasive Species of Minnesota. Pick up a copy, and join us in exploring this glimpse of a creepily not-quite-familiar future ecology!

Ruthanna Emrys’s A Half-Built Garden comes out in July 2022. She is also the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her short story collection, Imperfect Commentaries, is available from Lethe Press. You can find some of her fiction, weird and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.