All the drama around this year’s Kentucky Derby inspired me to do some rereading of favorite fiction about horse racing. Of course I had to revisit the Black Stallion series, the first dozen or so volumes of which I read as a tween and a teen. I can’t say I outgrew them as the rest of the series appeared through the Seventies and early Eighties—I was still and always irresistibly drawn to books about horses—but I had moved on to other authors and genres.

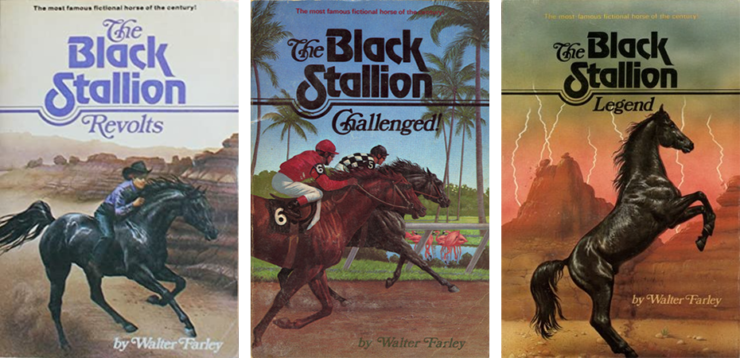

Thanks to the magic of ebooks and the glories of instant gratification, I scooped up a handful of later volumes: The Black Stallion Revolts, The Black Stallion Challenged, The Black Stallion and the Girl, and The Black Stallion Legend. My memory of the earlier entries is surprisingly clear, considering how long it’s been and how many books I’ve read in the interim. The two films, The Black Stallion and The Black Stallion Returns, have helped with that, but I’ve never forgotten the offspring. Satan, Black Minx, Bonfire the harness racer…they’re an indelible part of my personal mythos.

And let’s not forget the Island Stallion, Flame, whose saga intersects with that of the Black. I’ve written about him here before, because Farley dipped into science fiction in the second volume, The Island Stallion Races. This book is partially responsible for my tendency to write weird genre-benders.

My original reason for going back to Farley was to see if I remembered correctly that he wrote often about stallion behavior and misbehavior in and around racetracks. The Black, his hero-horse, was essentially feral, rescued from a desert island by the boy Alec. The horse was originally domesticated, and his owner tracks him down eventually, but all his natural instincts tended toward the wild and free. The only thing that connects him to a domesticated life is his bond with Alec.

A lot of this is wish-fulfillment fantasy. Only a registered Thoroughbred horse can run in Thoroughbred races including the three races of the Triple Crown. The Black, a desert Arabian, originally can only run match races against famous Thoroughbreds—he can’t be entered in formal races—but after a couple of books, Farley stops worrying about that. The Black’s purebred Arabian son Satan wins the Triple Crown, and his daughter Black Minx wins the Kentucky Derby. I suppose the reasoning is that key foundation sires of the Thoroughbred breed were Arabians; why can’t the Black continue the tradition?

I only recently learned that Walter Farley wrote The Black Stallion in high school and published it in 1941, when he was in college. It’s not just a boy’s adventure story in the classic mold, it was written by a person pretty much the same age as his protagonist.

Farley would never mature into a great prose stylist, and his plotting and characterization were pretty basic. He’s not a great literary talent. But he doesn’t need to be. From the very first, he knew how to tell a story. And above all, he knew horses.

The story he told in twenty volumes was a variation on a couple of themes. The boy and only the boy can handle the stallion. The stallion lives to run. He is the fastest horse in the world. Sometimes he runs for glory. Other times, especially in later volumes, he runs for the farm that his winnings have bought. His offspring likewise bring money and glory to their humans.

In every book, there is an antagonist. Sometimes it’s a financial or personal crisis. Often it’s a rival for the Black’s title of fastest horse in the world. Frequently it’s both. Usually there’s a race that determines the fate of the horse and the farm.

The Black is a superhorse. He’s gigantic for an Arabian, and gets bigger with every book, until he’s well over seventeen hands. That’s even huge for a Thoroughbred.

And yet he’s not a machine. In The Black Stallion Revolts, he snaps mentally under all the pressure he’s been put under. So much so that Henry the trainer sends him across the United States with Alec to take a rest break on a friend’s ranch. But of course, this being a Walter Farley novel, the would-be vacation turns into a whole new round of trauma. The plane carrying the boy and the Black crashes, and the Black escapes into the wild and Alec suffers a head injury that causes amnesia.

It’s actually rather difficult to read about the Black becoming a wild herd stallion and Alec having no memory of his name, his past, or his horse. I couldn’t wait for them to be reunited. That’s how powerful the bond between them is, and how strongly it comes through in book after book.

After a series of twists and turns and a villain or two, Alec and the Black are reunited in a high-stakes race. During the race, Alec’s memory comes back, just in time to save him from being arrested for a murder he didn’t commit. But that’s not as important to him, or to me as a reader, as the fact that the boy and his horse are together again at last.

Another exciting reunion is the one between the Black and the Island Stallion, Flame. These two stars of Farley’s universe met during another wild adventure when the Black and Alec were separated by a plane crash, this one in the Caribbean, but Alec doesn’t know that the stallions have met. Nor does he know Flame’s human, Steve Duncan, until Steve sends Alec a fan letter.

In the letter, Steve asks for Alec’s help to enter Flame in a major race in Florida. Steve needs the winnings to buy Flame’s island from the British government. Alec gives him advice as to how to qualify for the race, but doesn’t really expect anything to come of it.

Not only does Flame qualify, he proves to be a serious challenge to the Black’s supremacy on the racetrack. He’s just as fast, and just as wild—and the Black hates him. Alec resents that, and isn’t too happy with Steve, either. He’s not used to having a real rival in the racing world.

I think Farley wrote himself into somewhat of a corner here. He didn’t want either of his equine stars to lose a race, and he clearly wanted Steve to buy his island and allow Flame and his herd to live there, forever free. The Black is injured, which sort of evades the issue of a real head-to-head between the stallions, and Flame gets his win and his money.

Money has been an issue throughout the series. The need for it twists both people and horses. Steve makes his goal, but then keeps on racing, until Alec asks him if that’s what he wants. Is he going to keep pursuing race purses, or will he decide he’s won enough, and let Flame go back to his life of freedom?

Alec has to confront the same issue with the Black. How long can he keep racing? How long should he keep racing? The Black loves to run; he lives for it. But he’s starting to break down physically. Yet the farm needs his winnings in order to keep going.

These realities run through the later books, along with the fantasy of the perfect horse, and the romance between the horse and his boy. A more human romance surfaces in The Black Stallion and the Girl, in which an authentic Manic Pixie Dream Girl appears at Hopeful Farm and applies for a job. Henry the traditionalist is adamantly opposed to women in racing, but Pam has a gift with horses. She can even handle the Black, and in the end she not only rides but races him.

Buy the Book

A Half-Built Garden

It’s an interesting book, very much an artifact of its time: it was published in 1971. It comes out in favor of women in racing, and gives Alec an actual human love interest. Of course he would fall in love with a horsegirl. And of course the Black would love her, too.

One thing that comes out of this book is the sheer physical strength it takes to ride a top racehorse. It’s not just balance and core fitness. It’s upper-body strength. A jockey has to be able to control his mount’s speed, and that means a firm grip on the reins—which at a full gallop is like trying to hold back a runaway train. The horse is bound and determined to run faster than anything else on the track, and the jockey has to rate his speed, guide him through the pack, and convince him to slow down and stop once the race is over. That is by no means an easy task, and for many years the racing world did not believe a woman could do it.

In 1970, women jockeys were starting to prove they could. Farley gets on board with his version of the story, and gives her the greatest gift of all: the chance to race the Black. After thirty years of being a boy’s dream horse, the Black finally gets a girl.

By that point it seems Farley had run out of stories to tell about Alec and the Black. In The Black Stallion Legend, he does what writers have long been known to do when they’ve had enough. For Sherlock Holmes, it was the Reichenbach Falls. For Alec and the Black, it’s the fridging of the girl (on her way to Vienna to see the Lipizzaners—which is especially poignant for me) and the effective blowing up of the planet. Alec takes off into the West with the Black, ends up in Arizona—just as he did when he had amnesia—and he and his horse become the fulfillment of a Native American prophecy. And then a swarm of earthquakes shatters the world.

That’s one way to make sure there won’t be any more stories in that universe. I would have liked to see Alec and the Black in the postapocalyptic world, but that would have been a completely different kind of series. Farley could have killed them off, but even if he could have made himself kill the Black, his fans would have risen up in revolt. So he broke the world instead.

It seems fair. All things considered. The Black is an epic hero, and he deserves an epic denouement.

He’s also a pretty accurate representation of a dominant stallion, and when he’s racing, he’s doing it mostly by the book (except for the part where he’s not a Thoroughbred). Whole generations of horse kids in the United States have learned the basics about horses and racing from Walter Farley’s books. Even when they’ve moved on to other books and authors and to other breeds and types of horses, they always remember how it felt to dream about riding the fastest horse in the world.

Judith Tarr is a lifelong horse person. She supports her habit by writing works of fantasy and science fiction as well as historical novels, many of which have been published as ebooks. She’s written a primer for writers who want to write about horses: Writing Horses: The Fine Art of Getting It Right. She lives near Tucson, Arizona with a herd of Lipizzans, a clowder of cats, and a blue-eyed dog.