Six years ago I shattered my spine in a whitewater kayaking accident. The bone shards of my second lumbar vertebra sliced into my spinal cord, severing communication with the lower half of my body. Surgeons rebuilt my vertebra and scaffolded my spine with four titanium rods. I spent a year in a wheelchair. After hundreds of hours of therapy, my body established new neural connections. I learned to walk again. I’m tremendously grateful, and I know it’s an inspiring story. It’s the story that many want to hear. But it’s not the story I want to tell in my writing.

Sometimes, when the electric sting keeps me awake, when, in the middle of the night, lightning bolts charge from my right thigh, through my groin, and up to what remains of my second thoracic vertebra, I take my pain meds and try to remember how fortunate I am to be able to walk.

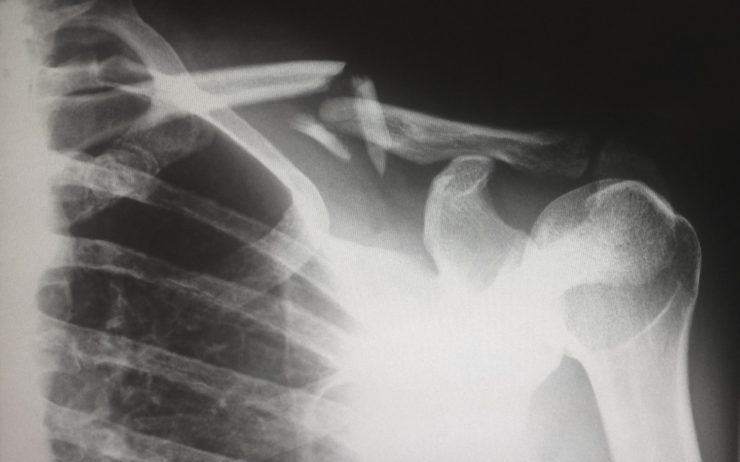

If I want to shirk the reality of such sleeplessness and agony, I turn to my phone and find a video clip titled “Learning to Walk Again” on CNN’s website. In the video, Anderson Cooper narrates a three-minute montage of my recovery. It starts with the x-rays and MRIs of the shattered ruins of my spine. Then a string of videos that show me struggling in a wheelchair.

When the somber music turns inspirational, the video cuts to me walking in a robotic exoskeleton, then a shot of me walking with crutches. And finally, with cinematic flair, I throw aside the crutches and take a few labored steps on the first anniversary of my injury, a tenuous grin plastered on my face.

The video is uplifting. It is immersive and heartening, and when I watch it, I briefly lose the version of myself who is lying awake in pain, forget that my legs feel like they’ve been dipped in lava. Riveted by the visual narrative, I almost forget I’m watching myself.

When it’s over, and the pain returns. The CNN clip seems like a lie.

Because I can stand and walk, my day-to-day life is measurably better, a truth captured and beautified in the video montage. And certainly the story has been inspirational for many people. But the video’s omissions—the acute and chronic pain, the problems with my bladder and bowels, the grief of losing the person I’d been—are as much a part of my story as relearning to walk is. Perhaps more so.

I decide I need a more encompassing narrative, one that considers exasperation as well as progress, suffering as well as triumph. One that makes meaning not just from overcoming, but from the ongoing lived experience of pain. Maybe I can even exorcize pain through writing, transmute it into narrative. So I invent Eugene, the protagonist of my novella Conscious Designs. I give him a spinal cord injury. Maybe together we can find some sense in our suffering.

Buy the Book

Conscious Designs

The more I get to know Eugene, the more compassion I feel for him. I consider giving him a shot at escaping his pain, so I send him into a near future where technology might be his savior.

Because I want to take away the visual signifier of his disability, his mobility impairment, I gift him a much more advanced robotic exoskeleton than the one that retrained my nerves. Eugene’s device is so svelte, it can hide under his clothes. He doesn’t even limp like I do, except when the machine fails.

But making Eugene mobile doesn’t make his disability go away. What really plagues Eugene are the unseen aspects of his spinal cord injury: the neuropathy, sexual dysfunction, incontinence, catheterization, bladder infections, pressure wounds.

Somehow I feel there should be a catharsis for me in heaping my pain on Eugene, but I only become more aware of my suffering. Sometimes my left foot feels like the blood is boiling within it. I imagine bubbles of hot gas moving through the veins, my muscles spasming, the tendons stretched like they’re going to snap. I take off my sock and inspect my foot, almost expecting to find some grotesque version of foot. But it appears normal. How strange that this normal looking foot can host such an inferno within. It’s attached to me, but it seems foreign. I can’t speak to my left foot beyond the dim motor signals of a few surviving neuro-channels. It speaks back to me only in its language of pain.

I begin to write what this pain tells me. I send its messages to Eugene’s brain. And so Eugene and I become connected through our defective neurology. We both look back at our able-bodied past, the people that we were before we became disabled, mourning their deaths. We both come to realize the paradox of pain: it’s universal, but intensely private. It should connect us, but it isolates us. Eugene and I spend the summer together, but together we find no truth in the chaos.

I want something better for Eugene. I give Eugene the option to escape his body by uploading his mind into a virtual world. A world in which pain can theoretically be edited out. A world entirely ruled by pleasure, a kind of hyperbole for the hedonism of our own time. Maybe if Eugene decides to upload his mind into this new digital world and create a virtual, able-bodied version of himself, then the real-world Eugene can come to terms with his spinal cord injury.

But I’m not confident in the truth of this story either. I’m not sure technology can free us from ourselves.

For me, Eugene’s experience in my novella is a more authentic portrayal of my disability than the story produced by CNN. The true nature of disability is an inner experience.

In Conscious Designs, Eugene is given the choice to branch his consciousness into two separate selves: one that would continue to suffer in the real world and one that would live free from suffering in the digital realm. To me, neither version seems desirable. I no longer want to be the real-world Eugene, whose neuropathy has become psycho-emotional pain, who can’t evolve beyond his self-pity and nostalgia for who he used to be. But I’m not sure I would eliminate my spinal cord injury either; with all its tragic elements, it has become an integral part of who I am.

I’m glad I don’t have to make this choice.

Nathanial White grew up in Maine and has lived in Mexico, Brazil, and Ecuador. His speculative fiction explores the human psyche, physical disability, culture, technology and consumerism. His debut novella, Conscious Designs, which was published in May, won the Miami University Novella Prize. He currently teaches Literature in the Rocky Mountains of Western Colorado.