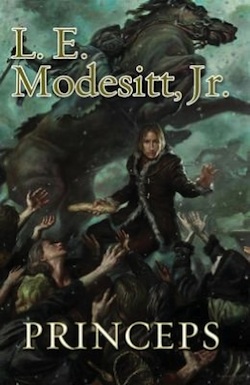

The latest installment in the Imager Portfolio by L.E. Modesit, Jr. will be released on May 22. With that in mind, we present an excerpt from this upcoming novel, Princeps:

The thrilling follow-up to Scholar—in which, after discovering a coup attempt and preventing a bloody civil war, Quaeryt was appointed princeps of Tilbor—begins a new episode in the young Imager’s life. Now second only to the governor, and still hiding his powers as an Imager, Quaeryt is enjoying his new position, as well as his marriage to Lord Bhayar’s youngest sister, Vaelora, when a volcanic eruption devastates the old capital of Telaryn.

He and his wife are dispatched to Extela, Telaryn’s capitol city, to replace the governor killed in the eruption. Quaeryt and Vaelora must restore order to a city filled with chaos and corruption, and do so quickly. The regiment under his command must soon depart to bolster Telaryn’s border defenses against a neighboring ruler who sees the volcanic devastation as an opportunity for invasion and conquest.

1

Quaeryt peered out from underneath the thick—and warm—comforter toward the nearest bedchamber window, its inner shutters fastened tightly. Even so, he could see frost on parts of the polished goldenwood. Supposedly, winter was waning, with spring some three weeks away, except that winter lasted into spring in Tilbor, even in Tilbora, the southernmost city in the province. The harbor in far-north Noira would not ice-out until the end of Maris, most likely.

A lithe figure wrapped her arms around him. “You don’t have to get up yet.”

“I do. It’s Lundi, and I am princeps, you might recall . . .”

“Dearest . . . do you have to?” The excessively pleading tone told Quaeryt that Vaelora knew he needed to rise, but that . . .

He turned over and embraced her wholeheartedly, finding her lips on his.

All too soon, he released her, wishing that he did not have to leave their bed. But then, it had been her desire to remind him of that.

Bhayar had been right. Quaeryt and Vaelora were enjoying being married, even if he’d never seen it coming. Vaelora had protested that she hadn’t either, that her brother had insisted she join him on his ride to Tilbora to keep her from the trouble she might have gotten into in his absence. Quaeryt had his doubts about her purported ignorance, but if that was the way she wished to portray matters, he’d certainly respect it. Then . . . it could have been that way. She hadn’t brought anything with her but riding clothes, and women who planned on being married usually thought about what they’d wear . . . unless she’d wanted to be able to insist she hadn’t known. And that was also very possible. He’d gone over all those possibilities for weeks, and probably always would . . . and he suspected she had planned that, as well.

He smiled.

“What is that smile for?” she asked, again in Bovarian, the language in which they conversed when alone—or in dealing with Bhayar.

“I was just thinking about the depths behind those seemingly guileless brown eyes.”

“I cannot believe you are interested solely in those depths.” Her slightly husky voice was both warm and slightly sardonic.

Quaeryt found himself blushing.

“You see?”

“Enough, lovely woman,” he declared with mock gruffness. “Your brother did say that we were to keep each other warm.”

“How, dearest, can I do that if you insist on getting out of this warm coverlet in this chilly bedchamber?”

Eventually, Quaeryt did leave the bed, as did Vaelora, and they washed and dressed quickly. Quaeryt was more than grateful for the warm water waiting in the bath chamber. Just the thought of the cold water in the officers’ quarters made him shiver.

Although Governor Straesyr, when he had been princeps, had lived with his wife and family in one of the row houses along the north wall of the Telaryn Palace, Bhayar had declared that such quarters were not suited to his sister. Quaeryt had suggested that the apartments on the upper east end of the palace proper—those that had been occupied by Tyrena, the daughter of the last Khanar of Tilbor before its conquest by Bhayar’s father—were most suitable for a princeps and that it would be most incongruous—not to mention grossly unfair—for the newly wed princeps to occupy the larger apartments of the former Khanar when his superior was the governor. That arrangement had been accepted by Bhayar and Vaelora and had certainly obviated possible tensions between Governor Straesyr and Quaeryt.

As Quaeryt began to pull on the fine browns of a scholar that Vaelora had insisted that he have tailored—because a princeps needed to look the position, as well as carry it out—he glanced at his left arm. It was still thinner than his right, while the skin was paler, not that his skin, ever so slightly darker than the pale honeyed shade of his wife’s complexion, would ever approximate the near bluish white of the Bovarian High Holders and royal family. Given the beating his body had taken in the battles against the rebel hill holders, he was glad that none of the injuries had been permanent, unlike his left leg, shorter than his right, presumably since birth, since he didn’t recall it ever being other than that.

Quaeryt waited until Vaelora was dressed—in light brown trousers, a cream blouse, and a woolen jacket that matched her trousers—before walking with her down the short corridor to the small cherry-paneled private dining room that had once been graced by Tyrena, who had been Khanara in fact, if not in name. There the ceramic stove radiated a comforting warmth.

Quaeryt seated Vaelora on one side of the table, then took his place to her left, at the end of the table, where Vaelora had insisted he belonged from the very first day of their marriage. In moments, a ranker in a winter-green uniform appeared with a teapot, a basket of warm dark bread, and a platter on which were cheese omelets and fried potatoes—exactly the same fare as in the officers’ mess, if served on porcelain, and if not quite so warm.

Quaeryt poured her tea, then his. “I do enjoy breakfast with you.”

“As opposed to dinner?” She raised her eyebrows.

“No. As well as dinner.” He grinned, enjoying the game, holding the platter so that she could serve herself.

“What will you do today?”

“What I do every day. I have a meeting at eighth glass with Cohausyt—”

“He’s the one with the sawmills who wants to pay to harvest timber on the lands Bhayar got from the rebel hill holders?”

“That’s the one. I put him off because I needed to find out what finished timber and planking goes for in Tilbora.”

“Did you?”

Quaeryt snorted. “In a way. I ended up finding out what the carpenters and cabinetmakers pay for wood. I had to work backward from that. Later, I have to meet with Raurem—he’s a produce and grain factor—to see if he can supply grain cakes for the regiments.” After eating several mouthfuls, and taking a swallow of the tea, he asked, “How are your plans coming for the spring reception?”

“Madame Straesyr has been somewhat helpful . . . as has Eluisa D’Taelmyn.”

Eluisa D’Taelmyn? Then Quaeryt realized she was talking about Rescalyn’s mistress, the Bovarian High Holder’s daughter the former governor had introduced as Mistress Eluisa. “She’s still here? I thought she had never married.”

“That’s her father’s name. He’s one of the lesser Bovarian High Holders. She has nowhere else to go, and Emra begged her husband to let her stay and teach their children singing and how to play the clavecin.”

“I heard her play once.”

“You told me. So did she. You upset her, you know?”

“I had that feeling. I was trying to see if Kharst was as terrible as they say.”

“He’s worse, according to Eluisa.”

Quaeryt wasn’t about to pursue that subject. “From your tone, I take it that neither one has been that helpful.”

“They’re really only interested in the wives of High Holders, not the wives of factors.”

Quaeryt wanted to shake his head. “How are your writings coming?”

“I write some every day.” She smiled. “The palace library has so many wonderful books.”

“I know. I even read parts of some of them.”

“You did mention that.” Vaelora took a sip of tea. “I wish this were hotter.”

“They have to carry it up from the kitchen.”

“I know. What do you think she was like?”

“Who?” Quaeryt had no idea to whom his wife was referring.

“Tyrena. The Khanara who wasn’t. You told me about those few scraps of paper you found with her writing.”

“She was too strong in a situation where there were no intelligent men to marry and manipulate.”

“Are you suggesting . . . ?”

“Me?” Quaeryt laughed. “All men react to women. All women react to men. Intelligent men and women react intelligently.” Usually, but not always, unfortunately. “From all the documents I’ve read, none of the men in power after her father fell too ill to understand were intelligent enough to listen to her. Probably the only man in Telaryn who might have been was your brother, and he’s much better off with Aelina.”

“Why do you say that?”

“Because you said that, and you know them both far better than I do.” He swallowed the last of his omelet, and the remainder of his tea. “I need to go.” He stood, then moved beside her chair, bent and kissed her neck. After a long moment, he straightened.

“Remember,” she said, “make the factors explain. In detail.”

Quaeryt smiled. “Yes, dearest.”

“You’re close to disrespecting me.” Her tone was bantering.

“Close doesn’t count.” Except in bed.

“I know what you’re thinking.”

He managed not to blush. “I’ll see you later.”

After leaving the third-level apartments, he made his way down the circular staircase to the second level, and then to the princeps’s anteroom and the study beyond. After almost a month and a half as Princeps of Tilbor, he was still slightly amazed when he walked into the study, although the view to the northern walls and the hills beyond was largely blocked in winter by the mostly closed shutters and hangings.

Princeps or not, he still met with Straesyr at the seventh glass of the morning every Lundi, and once he had checked with Vhorym, the squad leader who was his assistant, he walked back across the second level to the governor’s chambers.

“He’s waiting for you, sir,” offered Undercaptain Caermyt from his table desk in the anteroom.

“Thank you.”

Quaeryt closed the study door behind himself and took one of the seats in front of Straesyr’s wide table desk. “Good morning.” He spoke in Tellan, because that was the language used normally by the military—although officers were strongly encouraged to learn Bovarian, and failure to do so was usually a bar to promotion above captain.

“I have to say that you’re much more cheerful these days,” offered the governor, squaring his broad shoulders and running a large hand through stillthick silvered blond hair, as he straightened in his chair and pushed a map to one side.

“No one’s fighting or attacking, and the winter storms haven’t been that bad.” Quaeryt laughed ironically. “That’s according to the locals. I’ve never seen so much snow and ice in my life, and they’re saying it’s not so bad as it often has been.”

“You read Lord Bhayar’s last dispatch, I take it.”

That was a rhetorical nicety. Straesyr routed all dispatches to Quaeryt. Quaeryt, in turn, made sure that the few letters and dispatches, other than those of a personal nature, that came to him also went to Straesyr. “I did.”

“Once the roads to the south are clear, he’s ordered First Regiment to depart and take the route from Bhorael to Cloisonyt and from there to Solis.”

“And from there,” said Quaeryt dryly, “Bhayar will post them either to Lucayl or Ferravyl.”

“Ferravyl’s the greater danger,” said the governor mildly.

“But, if Bhayar can determine how to conquer Antiago, that offers an opportunity to obtain greater resources and to deny them to Kharst. Not to mention the fact that Bhayar has never felt that Autarch Aliaro treated Chaerila with the respect she deserved.” Which is why you worry about his notes mentioning “respect.”

“Chaerila?” Straesyr’s silver-blond eyebrows lifted.

“His oldest sister. She died in childbirth. According to Aliaro, her daughter died also. The daughter’s death was mentioned as an afterthought.”

“Did the Autarch express profound sympathy? Do you know?”

“I gained the impression that the sympathy was slightly more than perfunctory.”

Straesyr shook his head. “Has Lord Bhayar conveyed anything . . . personally . . . to you?”

“Outside of brotherly missives to Vaelora and two rather short and polite notes reminding me to respect her at all times, I have heard nothing since the wedding.” He paused, then asked, “How do Myskyl and Skarpa feel about the progress of Second and Third Regiments?”

“They feel that Second Regiment is largely ready and that Third Regiment will be ready for whatever duties it may be assigned by the end of spring. Commander Skarpa feels that if necessary, he could accomplish the last of the training while traveling.”

Quaeryt missed eating in the mess with the officers, but as princeps, he was not in the military chain of command, except in the event that Straesyr was killed or incapacitated. Twice, he had taken the governor’s place at mess night, once when the governor had the flux and once when a snowstorm had stranded him at High Holder Thurl’s estate, even though the estate gates were less than five milles from the Telaryn Palace.

“I’ll be meeting with Cohausyt at eighth glass,” Quaeryt offered. “You saw the revisions to the calculations based on your recommendations.”

“I did. Cohausyt will still do well, but Lord Bhayar can use the golds, especially if Kharst attacks.”

Or if Bhayar attacks Antiago. “I’ll be meeting with Raurem this afternoon as well. That’s about whether he can supply those grain cakes for travel fodder for the regiments.”

“He’s a produce factor, isn’t he, not a grain factor?”

“He is both, and Major Meinyt mentioned that he includes some rougher grains in his cakes, and they travel better, and the horses seem to do better. After you pointed out that there won’t be much forage when they’re leaving, I thought I should look into it.”

Straesyr nodded. “I’m already getting to the point where I’ll miss you when you go.”

“Go? I’m not going anywhere, not that I know.”

The governor smiled, and his icy blue eyes seemed to soften for a moment. “You manage to get things done. You’re old enough to understand, mostly, and young enough to try the almost impossible. You also know the difference between impossible and not quite impossible. You’re trustworthy, and Bhayar trusts you. There will be fewer and fewer advisors and officers whom he can trust totally. Sooner or later, he’ll need you again. For your sake, I hope it’s later.”

So did Quaeryt.

“Is there anything else?”

“No, sir.”

“Good. I’ll talk to you later.”

Quaeryt rose and made his way back across the second level of the palace. Cohausyt was already in the anteroom waiting when Quaeryt returned to his chambers.

“Princeps, sir.”

“Do come in.” Quaeryt smiled and kept walking.

The timber factor followed, and Vhorym closed the study door behind them.

Quaeryt gestured to the chairs, then settled behind his desk. “Lord Bhayar has agreed that the mature goldenwoods and oaks can be cut, but there are a number of conditions involved.”

“There are always conditions in everything,” said Cohausyt.

“There are indeed.” Quaeryt picked up the sheet of paper from the desk and handed it over. “Here are the terms.”

Quaeryt could see the tic in the factor’s left eye begin to twitch as the older man read the sheet of paper.

“I don’t know about leaving the softwoods untouched . . .” said the factor slowly.

“We know that the goldenwoods and oaks are heavier. There will be times when they bring down the evergreens. The terms state that you can only log those brought down incidentally . . . and not incidentally on purpose. Is that unreasonable?”

“Well . . . no, sir, but at times the best goldenwoods are surrounded by stands of pines, and there’s no way to get to them . . .”

Quaeryt listened until Cohausyt finished, then said, “You’d best make those points of access very narrow.”

“I suppose we can handle that . . . but no goldenwoods less than two-thirds of a yard across or two yards around at a yard above the ground?”

“That’s what the best foresters recommend . . .”

“Begging your pardon, Princeps, but foresters aren’t the ones who have to cut and mill the timber.”

“That’s true. They’re the ones who have to make sure that there are trees there for your sons to cut and mill.”

Cohausyt sighed and went back to reading, but only for a few moments. “. . . smoothing and tamping the logging roads?”

“Lord Bhayar doesn’t want large gullies in the middle of his woods.”

“But, sir, tamping takes men and time, and . . .”

Again, Quaeryt listened, before finally saying, quietly, “You are getting access to prime goldenwoods and oaks. There’s not a stand like them anywhere else in Tilbor.”

“But these terms . . .”

“I suppose I could post the terms and have others bid on them . . .” mused Quaeryt. Not that he wanted to, because Cohausyt was by far the most honest of the timber factors, and that meant that Bhayar would likely not be shorted on the golds from the sale of the timber. Quaeryt would have liked to have sold the rights for a flat fee, but there wasn’t a timber factor in Tilbor who possessed that amount of golds to pay up front.

“No . . . I’ll do what’s right, Princeps.” Cohausyt looked to Quaeryt. “I’ve heard you’re fair. Hard mayhap, but fair. It’ll take a bit longer, though.”

“I understand.” And Quaeryt did. Everything has to do with golds . . . and time. He understood that necessity, but even with the more honest factors, and Cohausyt was one of those, every term had to be spelled out in ink . . . and then explained.

He couldn’t say that he was looking forward to the meeting with Raurem. With all the nit-picking and endless details required in everything, it seemed, he understood more than ever why Straesyr had been more than happy to relinquish his duties as princeps to Quaeryt.

2

Jeudi morning dawned clear and bright, but there was still frost on the windows, and Quaeryt was most happy that the dressing chamber had a large carpet, because he could see frost in places on the polished marble floor. Even the lukewarm wash water pitchers showed warm vapor rising into the air.

“The pitchers—they look like the hot springs below Mount Extel,” said Vaelora. “Well . . . they don’t really, but they remind me of them. I wish we had hot springs here. A truly hot bath would be so wonderful.”

“If the springs were so wonderful, why did he move the capital from there?” bantered Quaeryt. He knew about the mountains of fire, but not about the hot springs. “Bhayar said his father did it because Solis was better located for trade and transport. He never mentioned hot springs in winter. But then, maybe he wasn’t one for baths.”

“Quaeryt . . .”

“Well . . . why haven’t I ever heard about these wonderful warm baths?”

“It’s not something we talk about.”

Quaeryt frowned. “I don’t understand.”

“It’s a family secret.” Vaelora smiled.

“Am I not part of the family now?”

“You are, and I’ll tell you because I don’t want any secrets between us. Promise me that you won’t keep secrets from me.”

“I promise.”

“I mean it.”

“I understand,” Quaeryt replied, and he did. He already knew that when she set her mind to something, nothing changed her course.

“He did it because of a vision.”

“A vision? Lord Chayar was a most practical man. I can’t believe he saw visions.”

“He didn’t, dearest.”

Quaeryt sighed. Loudly.

“Father moved the capital to Solis because Grandmere had a vision. She didn’t call it that. She said it was foresight. She was mostly Pharsi. Everyone knows that, but no one talks about it. She had more than a few visions, and Father said he’d not listened to her only once, and he wished he had. So when she said she’d seen Extela in ruins and parts of it covered with ash and lava, he didn’t argue.”

“Well . . . so far as I know, Extela’s still doing quite nicely.”

“It is. Sometimes the mountain rumbles and at times it spews out ash, but the ash and hot springs are why the uplands are so fertile.”

“And he uprooted everyone and rebuilt Solis because of a vision?” Quaeryt tried not to sound appalled. “One that never happened?”

“You didn’t know Grandmere.”

Quaeryt considered. If her grandmother was anything like Vaelora, I can see. . . “You take after her, don’t you?”

Vaelora offered a rueful smile, one of the few that Quaeryt had seen on her face. “That was what Mother claimed. Bhayar said I have her spirit and that I was born to plague him.”

Quaeryt grinned broadly. “So . . . that was why—”

He didn’t get any farther because a good portion of the cold water pitcher splashed across his chest and face.

Later . . . when laughter subsided, with domestic order restored, and Quaeryt stopped shivering and got dressed, they did manage to reach the private dining chamber, where, thankfully, the stove had warmed the air to an almost pleasant state, pleasant for winter in Tilbora, reflected Quaeryt as he took a welcome swallow of tea.

“Dearest . . . are you still going to ride to the scholarium this morning?”

“Yes, even after a cold dowsing.” Quaeryt managed not to frown, then saw the anxious expression on Vaelora’s face, an expression he knew he was meant to see, since she was excellent at avoiding what she did not wish to reveal. “Would you like to accompany me?”

“If you wouldn’t mind too terribly. Emra . . . I had thought to spend some time with her, but both her son and daughter are quite ill with the croup. So is Eluisa. That means I won’t see her, either, and I was looking forward so to learning some of the pieces by Covaelyt and Veblynt.”

“Isn’t there sheet music? You play well enough . . .”

“She only has one copy of each, and she is most guarded in holding them. You can understand why that might be, and I’d rather not have to copy it line by line.”

Left unsaid was that there were no copyists at the Telaryn Palace except those attached to the regiments, and neither Quaeryt nor Vaelora felt it proper to request personal copying from them.

Quaeryt looked at his wife. “You miss Aelina, don’t you?”

“Terribly. I cannot tell you how much . . . She was the only one . . .”

“Except Aunt Nerya, of course,” teased Quaeryt.

Vaelora looked at her husband with wide guileless eyes. “I should have mentioned her.”

“Was she that bad?”

“You know what I feel.”

Quaeryt did, and did not press. “I’ll be leaving at half past seventh glass, and I’ll have a mount for you. Please dress warmly. There’s a bit of a wind.”

“Yes, dearest,” replied Vaelora in a voice that Quaeryt knew as her sweet and falsely submissive one—and that she knew he recognized as such.

He laughed.

The last quint of breakfast passed too quickly, and before that long, or so it seemed to Quaeryt, he had sent word down to have his mount and Vaelora’s ready, finished reading the various dispatches, and was donning his heavy riding jacket, the fur-lined leather gloves, and the fur-lined cap he’d taken to wearing whenever he was outside for long.

“Vhorym . . . I’ll be riding over to the scholarium. I likely won’t be back until close to second glass.”

Vaelora was actually mounted and waiting for him in the palace courtyard, as was the squad from Sixth Battalion who would accompany them. Quaeryt glanced at the sky, with the high gray clouds that were all too common in winter, then mounted quickly. As he and Vaelora followed the outriders through the eastern gates of the palace—the only gates—and down the stone-paved lane across the dry moat, now half filled with drifting snow, he could barely see over the snow piled on each side of the lane, even on horseback. The wind was raw and bitter, as it usually was when it blew out of the east.

Snow crunched under the hoofs of their mounts as they rode through the lower gates and onto the main road to the south.

“We’re only a few weeks from spring,” he said cheerfully.

“That’s spring in Solis,” returned Vaelora.

“True enough. We’ll be fortunate to have frozen mud by then.”

The wind was bitter enough that neither said that much on the glass-long ride to the scholarium. In fact, Quaeryt said almost nothing at all until they rode up the snow-packed lane and past the main building of the scholarium before reining up opposite the middle of the rear porch.

“Squad Leader, put all the mounts in the stable. You and the men wait in the tack room in the stable. If the stove isn’t fired up, you have my authority to do so. I will need two rankers to escort my wife.”

“Yes, sir.” Rheusyd glanced at the stable to the rear of the main building. “Might already be fired up, sir. There’s smoke rising.”

“I hope so. It’s been a cold ride, at least for us.”

“Been on colder ones, sir, but a warm stove would be good for the men.”

Vaelora and Quaeryt dismounted, climbed the steps, and crossed the wide and empty covered porch.

As he held the door for her, he said, “There’s a stove in the main hall outside the master scholar’s study. You can warm yourself there. I imagine you’ll have company before long. Besides your escorts.”

Vaelora raised her eyebrows, then brushed the combination of water and melting frost from them. “Oh?”

“There aren’t any women here, except for the cooks and a few others, and none are as beautiful as you.”

“Who could tell under all these garments?”

“They could tell.” Quaeryt turned as the gray-haired and round-faced master scholar hurried toward them. “Nalakyn, I’d like to present you to my wife, the Lady Vaelora.”

The master scholar bowed deeply, his eyes avoiding those of Vaelora, as was proper. “We are most honored to have the sister of Lord Bhayar here, and especially in weather such as this.” He straightened. “I would offer you my study or that of the scholar princeps, but neither has a stove or a hearth. With your permission, I will have a comfortable chair brought for you so that you can warm yourself by the main stove here.”

“You’re most kind, master scholar.”

Nalakyn flushed. “It is not often we are so honored.”

Once Vaelora was seated before the stove, the two rankers discreetly standing against the wall several yards away, Quaeryt and the other two scholars were about to retire to the much cooler study of the master scholar when another figure hurried through the rear door, a young man wearing the robes of a chorister. Snow sprayed from his boots.

“Princeps! Sir?”

Quaeryt stopped and waited. “Gauswn! It’s good to see you. How are you doing? How is Cyrethyn?”

“He is in good spirits, sir, but he is frail, and he begs your pardon for not joining me, but he is not so steady on his feet as once he was.”

“Has he let you deliver any homilies?”

“Let, sir? He insists I do two a month.” The young chorister looked embarrassed. “One of them was taken from what you said.”

“I’m sure I probably gleaned it from someone else.”

“I don’t think so, sir. There’s nothing like it in any of the chorister books.” Gauswn paused. “I mustn’t keep you, and Cyrethyn needs my help. I did want to come and thank you again. This is where I should be.”

“Before you go,” said Quaeryt, “you should meet my wife, Vaelora.”

Gauswn bowed deeply. “Lady . . .”

Quaeryt smiled at Vaelora and eased away.

After he entered the master scholar’s study, he took one of the chairs in front of the desk. “Let’s see the ledger, Yullyd.”

“Here, sir.” The scholar princeps handed the master ledger he had carried to Quaeryt, then took the other seat. “The marker is where the entries for Ianus are summarized. I finished them on Lundi.”

Nalakyn slipped into the chair behind the desk, but sat forward, apprehensively.

“Is there someone you can train to do the day-to-day entries?”

“Young Syndar has been helping me.” Yullyd’s voice was level.

Quaeryt wasn’t surprised. From the time he’d delivered a letter from Syndar’s father Rhodyn, he’d known that the student scholar would likely try anything not to leave the scholarium. “His father wants him to go back to Ayerne? Is that it?”

“He says he won’t go, and that his younger brother is far better suited to being a holder.”

“That’s likely true, but it’s not our decision.” Quaeryt frowned. “How good a scholar is Syndar? Would he make a good bursar in time?”

“He’s very accurate with the figures, and very neat,” replied Yullyd. “He truly wants to be a scholar.”

“He also assists in teaching the younger students. He’s been most helpful there,” added Nalakyn.

“Draft a missive to Holder Rhodyn for my signature. Make it very polite and most courteous. Tell him that I know of his desires and wishes for his sons, but I had thought he would like to know that I have learned that Scholar Syndar has proven to be exceedingly gifted as a scholar and is being considered for training as the bursar of the scholarium and that he has a future as a scholar. Because of this, tell him that I had thought he would like to know of this before making any final decision on what might be best for his sons.” Quaeryt paused. “Write that up as soon as we finish. I’ll wait for it.”

The two exchanged glances.

“I can send it tomorrow. Otherwise, it will be another week. I want him to get it before his mind is even more set and before it’s even close to spring planting.”

During the winter, now that Bhayar had destroyed the last of the ship reavers, couriers from Tilbora could take the coastal roads directly south, well past Ayerne, and then turn west through Piedryn on a more direct southern route to Solis. There was no reason Quaeryt couldn’t pay the courier out of his own funds to stop and deliver the missive to Rhodyn—the holding house was less than fifty yards off the road.

Yullyd nodded. “Yes, sir.”

“Is there anything else?”

“Sir . . . we have . . . some difficulty,” said Nalakyn. “What kind of difficulty?”

“Ah . . .” Nalakyn drew out the single syllable, as if he were at a loss for words.

“Chartyn,” said Yullyd. “He’s not the problem. The fact that we accepted him is.”

“There’s another factor with an imager son?” asked Quaeryt.

“Actually . . . well . . . ah . . .”

“Yes,” said Yullyd. “He’s not a factor. He’s a freeholder to the north. One of those with not enough lands to be a High Holder and too well off to be a mere grower or crofter. He heard about Chartyn. He’s well able to pay for his son.”

“I fail to see the problem. Has Chartyn created any difficulties?”

“No, sir . . . but . . . imagers in a scholarium?” asked Nalakyn almost plaintively.

“There are imagers in the Scholarium Solum in Solis. Why shouldn’t there be imagers here?”

“We don’t have any rules for imagers, sir,” said the master scholar.

“Would it help if I wrote out a draft of some rules? I knew the imagers at the scholarium fairly well, and they did tell me some things.” Not that you don’t know far more than Voltyr did, or even poor Uhlyn, but the scholars don’t have to know that. “You could start with those and refine them as necessary.”

“But . . . this is a scholarium . . .”

Quaeryt looked hard at Nalakyn, feeling almost like imaging his disgust and anger.

The master scholar paled . . . then swallowed. His voice was barely audible as he replied. “Whatever you say, sir.”

“Nalakyn,” Quaeryt said gently, “I went out of my way to save the scholarium when most of Tilbora was ready to burn it and all of you because of what Zarxes, Phaeryn, and Chardyn—oh, and Alkiabys—were doing. Lord Bhayar and Telaryn need safe places for both scholars and imagers. Not just scholars. Not just imagers. Both.”

Yullyd glanced at Nalakyn.

“I understand, sir, It’s just that . . .”

“We all have to change with the times. I wouldn’t be surprised if, in a few years”—if not even sooner—“Lord Bhayar will need imagers.”

“You mean if Rex Kharst conquers Antiago and captures the Autarch’s imagers?” asked Yullyd.

“That’s certainly a possibility,” agreed Quaeryt. “It would be useful to have some imagers who could create Antiagon Fire or combat it.” Not that Quaeryt had any idea of how to do that himself.

“How . . . would they combat it?”

“Image sand over it, I suspect. That usually damps most fires, even bitumen fires.” That was a guess on Quaeryt’s part, but he thought it would work, since stone and earthworks were impervious to Antiagon Fire. “I’ll have those draft rules to you within a week, sooner if I can. Tell the holder—what’s his name . . . his son’s name, too?”

“His name is Kryedt. The boy’s name is Dettredt.”

“Tell Holder Kryedt that the boy is accepted, under the usual provisions requiring good conduct and obedience to scholars.”

“Yes, sir,” replied both scholars. While Nalakyn’s tone was not quite resigned, Yullyd’s was more enthusiastic.

“Now . . . I’ll wait outside in the main hall while you draft that letter to Holder Rhodyn.”

Quaeryt stepped out to rejoin Vaelora, noting several students hurrying away as he neared. One he knew—Lankyt.

“What did young Lankyt have to say to you, dearest?” asked Quaeryt quietly, not wishing his voice to carry beyond Vaelora.

“Which one was he? The slim brown-haired one with the shy smile?”

“How did you know that?”

“I didn’t, but you wouldn’t have known who he was unless he stood out in some way. He was the most respectful and well-spoken.”

“His father is the holder in Ayerne.”

“Rhodyn, is it?”

“Yes. He was most kind when I escaped the ship reavers and was recovering.”

“He spoke highly of you when we spent the night there.”

“He’s a good man. I just hope . . .” Quaeryt went on to explain.

Vaelora listened, then nodded. “You’re offering a strong suggestion, but not demanding.” She smiled mischievously. “You are suggesting, between the lines, that he’d be a fool not to agree.”

“What else could I do?”

“You could let him do as he pleases without saying a word . . . but that’s not who you are. You’ve proved that in dealing with my brother.”

Quaeryt shrugged.

“The chorister? Gauswn . . . he was most complimentary. Is he the one who was an undercaptain?”

“He was.”

“He said that it was almost a shame you hadn’t been a chorister, but that he’d seen you were destined for greater deeds.”

Quaeryt winced. “I fear he thinks I’m another Rholan.”

“Would that be so bad, dearest?”

“For a man who doesn’t know whether there even is a Nameless, it would be.” Quaeryt shook his head.

“You’re too hard on yourself.”

“Not in that.”

Vaelora shook her head.

Shortly, Yullyd reappeared with the letter. “Sir?”

“Thank you.” Quaeryt read it, then nodded, took the pen from the scholar princeps, and signed the missive. “Very good, Yullyd.”

“Thank you, sir.”

After the ink dried, helped by Quaeryt’s holding the paper near the stove, he folded the sheet and slipped it into the inside pocket of his jacket.

In less than a quint, they were on the road back to the Telaryn Palace, riding directly into the wind, which seemed to be slightly stronger than on the way to the scholarium.

“Are you still glad to be accompanying me?” asked Quaeryt dryly.

“Yes. It was good to get out.”

“What did you think of the scholarium?”

“Everyone was most polite,” observed Vaelora.

“You might have noticed all the deference was to you, my dear lady. Quite manifestly obvious, I would say.”

“That might have been, but the respect was for you. Master Scholar Nalakyn looked somewhat chastened when he bid us good day.”

“He was reluctant to take on another paying student because the boy is an imager.” Quaeryt snorted. “As if the boy will not have enough problems. An education will help.”

“It helps some, dearest. Others it is wasted on.”

“True. But if he’s one of those, he goes back to his father. He deserves the chance. What he makes of it is up to him. Did Chaerila ever write or say anything about the Autarch’s imagers?”

“Not to me.” Vaelora frowned in concentration. After a moment, she said, “I remember, though, something that Aelina said. Chaerila complained in a letter to her that she was almost a prisoner in the palace, but at least she wasn’t walled up in a compound with metal behind the walls, the way the Autarch’s imagers were.” She paused. “What are you going to do?”

“Write up a set of rules. Then you’ll read them and tell me what to change and improve?”

“You aren’t asking me.” A mischievous smile appeared. “Isn’t that a form of disrespect?”

“I respect your judgment and intelligence so much that I know you’d want these rules to be as good as we can make them.”

Vaelora laughed.

Quaeryt smiled happily—until the next gust of bitter wind whipped around and through him, and he shivered almost uncontrollably.

And this is a warm day for winter.

Princeps © L.E. Modesitt, Jr. 2012