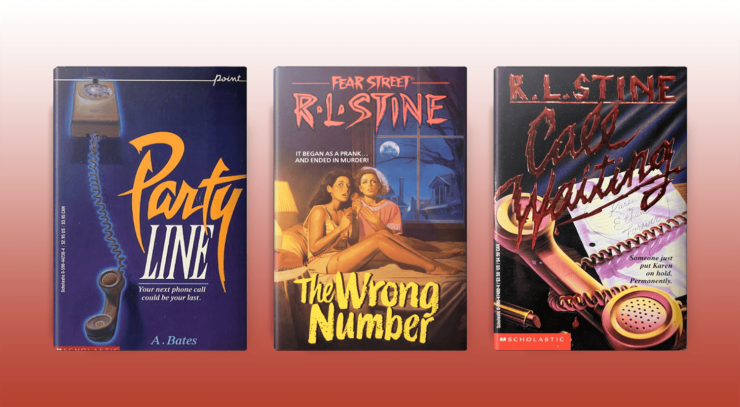

While some elements of ‘90s teen horror remain relevant to a contemporary reading audience—like friendship drama, boyfriend troubles, trying to fit in and be accepted by one’s peers—others already feel like vestiges of a bygone era, like mimeograph machines and landline telephones. If these characters just had cell phones or access to the internet, it would change everything. Not sure where your friend is and worried she’s in danger? Text her. You’re being followed by some creepy dude who just might be a murderer? Call 911. Mysterious new guy school? Google him and stalk all his social media looking for his dark secret. But the guys and girls of ‘90s teen horror have none of these options and find terror on the landline in A. Bates’ Party Line (1989) and R.L. Stine’s The Wrong Number (1990) and Call Waiting (1994).

While each of these books features a different dangerous scenario, one common theme they all share is that in these pre-caller ID days, the characters have no way of knowing who they’re talking to, which creates ample opportunity for anonymous mayhem and harassment. In Stine’s Fear Street novel The Wrong Number, Deena Martinson, her friend Jade Smith, and Deena’s half-broth Chuck are the prank callers themselves, with the girls making sexy anonymous phone calls to boys they like (all good fun and the fellas don’t seem to mind) and Chuck calling in a bomb threat to the local bowling alley (a pretty extreme escalation). Things get real, though, when Chuck starts talking smack about Fear Street, telling the girls “Don’t you know that every small town has some place like Fear Street? It’s all a bunch of garbage just to make a boring place a little more interesting” (30). Chuck just moved to Shadyside and doesn’t know any better, so he prank calls a random number on Fear Street, and ends up hearing a woman getting murdered. (The tables are turned in the sequel Wrong Number 2, when Deena and Jade start getting phone calls of their own.) In Call Waiting, Karen Masters is the recipient of the creepy phone calls, as someone repeatedly calls to tell her that they’re watching her and planning to kill her. Party Line is a bit more complicated, as Mark Carney calls into the local teen party line (976-TEEN), where kids can call in on a collective line to talk to teens in their area. Mark is a bit unhealthily obsessed with the party line and loves chatting anonymously with strangers (preferably girls), only to find that someone is using the party line as a way to find and set up meetings with young women to kidnap, though with people disguising their voices and using fake names it’s tough to figure out exactly who the bad guy is and how to stop him.

In these novels, phones are a status symbol and marker of social capital, a gateway to popularity and a reflection of their economic position and privilege. The teens in The Wrong Number always make their calls from Deena’s phone because her dad’s a high-level executive at the phone company, so her phone has all kinds of bells and whistles, including a speakerphone function, which is an obvious must-have for prank-calling teens. Call waiting is a pricey add-on that ensures the user doesn’t miss an important phone call because they’re tying up the line with another conversation, which becomes a central plot point in Stine’s Call Waiting. And Mark’s Party Line calling is a point of contention at home, because these party line calls are expensive: “fifty cents for the first minute, and twenty-five cents for each minute after that” (2). The party line provides Mark a connection to peers that he struggles to achieve in face-to-face communication and he racks up a giant phone bill, a disaster for his single mom’s household budget. One of the first sustained and meaningful connections he establishes with a girl on the party line is about a hack she found for pushing specific phone buttons simultaneously to simulate the sign-off signal, which means that they can stay on the line, not get charged, and eavesdrop on others who think they’ve left the line.

Buy the Book

Just Like Home

One of the most alluring elements of these phone calls is that they allow the caller to pretend to be someone else, to try out identities and personas that elude them in real life. In The Wrong Number, “shy, quiet little Deena” (18) becomes a seductress, catching the attention of Rob Morell, one of the popular guys in school, even though she’s never been brave enough to talk to him (let alone come on to him) in person. This anonymity is what keeps drawing Mark back in Party Line as well, in spite of his guilt about the cost. As he reflects, “invisibility … [is] the whole secret here. We can open up to people on the Line because they can’t really see us at all. It’s almost like a dream world where we just imagine the other people, except they talk out loud to us. We’re all invisible and safe” (28). With the reassurance that no one really knows who he is on the party line, Mark is able to be more confident and outgoing, “practice” that eventually carries over into the real world where he goes out on dates with two different girls. For teens who are self-conscious and mired in self-doubt, the anonymity of the phone line offers freedom and a chance for experimentation, self-expression, and connection that they’re otherwise missing.

While this anonymity is freeing and fun for the callers, it is an integral part of the horror for those on the receiving end of these phone calls: they don’t know who the caller is, so there’s no way for them to effectively protect themselves. Mark and Janine (whose name is actually Alise) know that there’s someone lurking on the party line and preying on young women, but because everyone gives fake names and can disguise their voices, they don’t know who he is or how to stop him, running through a long list of suspects that ends up including one of Mark’s best friends and his English teacher. In Call Waiting, someone is calling and threatening Karen, saying things like “I can see you, Karen … I’m your worst nightmare. I’m going to kill you” (136, emphasis original), leaving Karen constantly on edge but with no way to figure out who is calling or how she might be able to ensure her safety. The caller whispers, so she can’t even determine the caller’s gender and she has no way of knowing if the caller is just trying to scare her or actually means to do her harm. The same is true in Wrong Number 2, where Deena and Jade start getting threatening phone calls vowing revenge and are unable to tell how much danger they might actually be in.

If the drama of being the caller or the one being called isn’t enough, Stine and Bates further complicate these dynamics, sometimes in problematic ways. In Call Waiting, Karen frequently gets the threatening phone calls on the other line while she’s talking to her boyfriend Ethan, she panics, and he chivalrously comes rushing over to her house to comfort and protect her from whoever it is that wants to hurt her. But then it turns out that Karen’s family doesn’t have call waiting—she’s been inventing threatening calls to keep Ethan from breaking up with her. When her mother, her brother, and Ethan discover Karen’s subterfuge, she refuses to take it seriously, repeatedly saying “this is so embarrassing” (119) and dismissively saying that “I did a dumb thing, that’s all” (120), particularly defensive when her mother insists that Karen speak with a mental health professional. As horrifying as this is, it’s actually just one small part of Karen’s obsessive behavior, as she sits in her car outside of Ethan’s house to see if he’s been out with someone else and harasses Wendy, the other girl she thinks Ethan’s interested in. After Karen’s deception has been discovered, she actually starts getting threatening phone calls. These calls add an extra layer of horror to the scenario because after her previous stunt, no one really believes Karen is getting these calls and she even begins doubting her own sanity, wondering if she’s hallucinating them. This second round of calls are actually real though and turn out to be from her best friend Micah, who has been seeing Ethan behind Karen’s back. Karen can’t trust her boyfriend, her best friend, or herself. But the most problematic part of this whole scenario is that Karen’s behavior actually works—the stalking, the fake phone calls, the damsel-in-distress manipulation—and she gets the guy. So maybe Stine’s takeaway is that the end justifies the means and all’s well that ends well? Yikes.

The conflict in The Wrong Number is pretty straightforward: Chuck is framed for Mrs. Farberson’s murder after hearing her cries for help on the phone and going to the house to try to intervene, and Deena and Jade spend the rest of the book working to clear his name. Apart from the mystery-solving drama of The Wrong Number, the main interpersonal conflict is between Deena’s father and Chuck, who he allows to sit in jail longer than necessary and even when he knows Chuck is innocent because he thinks it “might teach Chuck a lesson” (161). The interpersonal relationships grow more complicated and contentious in Wrong Number 2, as Chuck begins making threatening calls to Jade when he finds out that she’s seeing other guys while he’s away at college (and later to Deena as well, because he figures it’ll be suspicious if Jade’s the only one getting these creepy calls.) Deena and Jade also discover that Stanley Farberson’s mistress Linda Morrison is actually the mastermind and she talked Stanley into stealing his wife’s money and murdering her.

Things are further complicated in Wrong Number 2, when Deena and Jade start getting scary phone calls again. After trying to murder them with a chainsaw at the conclusion of The Wrong Number, Stanley Farberson was caught and put in prison for the murder of his wife. With Stanley behind bars, Deena and Jade aren’t sure if he’s calling from prison (he’s not), if he’s out of prison and once again a threat to them (he isn’t but he will be), or if there’s an entirely new horror with which they must contend (yep, it’s Linda). Many of Stine’s Fear Street books are light on violence, with lots of head conking and people knocked unconscious and not many fatal shootings or stabbings – but the Wrong Number books are definitely an exception. In the final scenes of The Wrong Number, Stanley is using a chainsaw to try to cut down the tree in which the girls are sheltering, with the clear intent of chainsawing them if they’re not killed in the fall. The chainsaw makes a not-so-triumphant return in Wrong Number 2, where Stanley meets his (surprisingly gruesome) end. And in addition to being more than happy to murder her former lover, Linda also leaves the teens for dead when she ties them up in the basement, lights a candle that will ignite some nearby gasoline, and heads out, giving them plenty of time to ponder their horrific, looming fate.

Linda claimed that she was terrified of Stanley, feared for her life, and wanted to be the girls’ friend … right up until she tried to murder them. Taking Stine’s Call Waiting and the Wrong Number books together, the message seems to be that if a woman tells you she’s being threatened, she’s probably making it up and if she says she’s your friend, she’s either trying to steal your boyfriend or kill you.

In Party Line, the characters are refreshingly realistic and proactive. When Mark and some of his friends talk about the girls who have gone missing, his friend Marcy says “You know, I really resent being vulnerable … I don’t like being afraid. I don’t like having to walk with someone else for safety, even on my own street, in my own neighborhood” (40), a straightforward acknowledgement and interrogation of teen girls’ experiences. When one of their friends suggests taking a self-defense class, Marcy is enthusiastic, telling the boys that “you two probably ought to take one, too. Guys may not be victimized as often, but it still happens” (40), a pretty radical sense of awareness and one that the boys accept, attending the self-defense class along with their female friends, with no sense that this is an admission of weakness or an emasculating experience, but rather the smart and responsible thing to do. The consequences of real-world violence are foregrounded by their self-defense instructor Vince, whose wife was mugged and murdered. The friends find this self-defense class both enlightening and empowering, which makes it even more horrifying when they discover that Vince is the one who has been kidnapping the girls from the party line, telling police that “I wasn’t going to hurt anyone. I just wanted someone near me. People to talk to” (163). Mark’s psychologist explains Vince’s behavior as the result of unprocessed trauma following his wife’s murder, describing it as “a tortured person’s attack against a world he couldn’t control, couldn’t understand, and couldn’t fit into” (163). Mark’s psychologist uses Vince’s example to emphasize the importance of Mark processing his own trauma in healthy, productive ways, a coming to terms which is depicted as realistically messy and still very much in process in the novel’s final pages. Bates further complicates the neat conclusion of Party Line with the revelation that Vince only kidnapped four of the six missing girls (the other two were runaways who were found or came home on their own), further emphasizing that there’s no one single explanation that answers every question, no tidy and complete resolution in the real world.

In Party Line, The Wrong Number, and Call Waiting, the phone serves to connect these teens to one another, the larger social world of their peers, and in some cases, to themselves, as they use the anonymity provided by the phone line to figure out who they are and who they want to be. But the opposite is also true, as these phone calls serve as a threatening source of danger and a way for them to engage in manipulation and harassment, like the calls Karen claims she has received in Call Waiting and Chuck’s calls to Jade and Deena in Wrong Number 2. When their phone rings again, it might be better to let the answering machine get this one. At least that way, there might be some evidence for the police.

Alissa Burger is an associate professor at Culver-Stockton College in Canton, Missouri. She writes about horror, queer representation in literature and popular culture, graphic novels, and Stephen King. She loves yoga, cats, and cheese.