Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches.

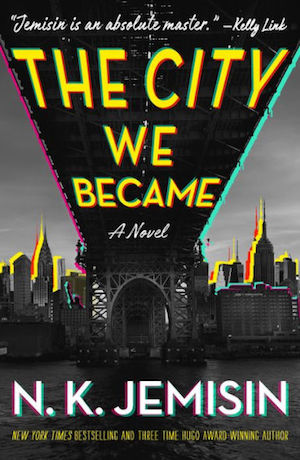

This week, we continue N.K. Jemisin’s The City We Became with Chapter 8: No Sleep in (or Near) Brooklyn. The novel was first published in March 2020. Spoilers ahead!

“I’m the core of this city, either live or compost.”

Chapter 8: No Sleep in (or Near) Brooklyn

In the vacation unit of her family’s adjacent brownstones, Brooklyn’s in her old bedroom, the window cracked to let in the comforting sounds of the nighttime city. Back in her teens, before she became MC Free, she’d look at the sky between burglar bars and make up freestyle lyrics in the dark, never expecting to transform into a living embodiment of the “wild, incredible, stupid-ass city” she loves. Still, she’s okay with the change, more than she expected.

Her daughter Jojo calls from next door to ask when Brooklyn’s coming home. Not that she, all of fourteen, could possibly be missing her mama. The two end up at their respective windows, screens raised so they can lean out to look for whatever stars make it through the light pollution. Then Brooklyn notices a strange glow in the backyard of the other building. It emanates from a sort of giant white spider, scissoring itself along on four cylindrical legs, “an eldritch daddy longlegs, brought to you by the letter X.”

Jojo can see it too. More appear, and Brooklyn orders Jojo to shut her window and get her grandfather into his wheelchair. Jo obeys. The spiders, Brooklyn realizes, are like the feather-sprouts she battled earlier—everything of the Enemy’s seems to radiate “the same prickling, jangling antithesis of presence,” so that they “erase some tiny part of New York with every iota of its space they occupy.”

Barefoot, armed only with a collapsible baton, Brooklyn races out of the brownstone. She’s horrified to see dozens of X-spiders swarming the facade of the neighboring building. It was a mistake to assume that both houses would enjoy the protection of her “Brooklyn-ness”. Both may be her legal property, but human legalities don’t matter when she never went inside the other with as avatar.

An spider flattens to slide under the front door. It’s obviously a trap, using her loved ones to lure her out of safe space. She fights panic and recognizes in her panting breath “a perfect b-girl backbeat.” Tonight, as yesterday, lyrics must be her weapons, her conduit into power.

With the city strengthening her, Brooklyn shoulders open the front door. The spider’s been busy: Strands of white light, a living web, try to snare her in the hall. She tears through them and rushes to her father’s room, where another spider has slid through the window frame, and puffed back into three dimensions, tooth-ringed mouths opening all over its legs. Brooklyn slams a palm into its seemingly insubstantial body and encounters a jittery cold “less like something alive than like a sack of infinitesimal Legos tumbling apart and trying to reform under her hand.” But she, too, is vastly multiple, two and a half million people, a collective will screaming, “We are Brooklyn,” a force more powerful by far than whatever holds the spider together.

Brooklyn crushes the thing, improvizing her diss track as she goes. Then she drops to the floor—her floor, her house, her family, her city—and a wave of “city-energy” ripples so powerfully from her palms that all New York “shivers and rings with one soundless tone.” Unlike Manhattan, she doesn’t try to merge herself into the whole city. To be Brooklyn is enough for her, and she lays claim to every part of it, willing the contamination that’s spread throughout the neighborhoods to die.

And die it does.

Having purged her borough without the support of the others leaves Brooklyn utterly drained. She collapses with a grin, muttering “Still got it.” Manhattan arrives and takes her hand, infusing her with enough strength to pull her back from the brink of coma. She drifts toward sleep knowing that all the borough avatars will need to do much the same service for the embodiment of New York.

Buy the Book

A Half-Built Garden

Whenever they find him.

Brooklyn sleeps until late afternoon. In the kitchen she finds Manhattan, Padmini, her father, and Jojo sitting in silence around the table, transfixed by a business letter lying open nearby. It came by certified mail, she sees. Then she sees the fury in her father’s face.

“This is an official notice of eviction,” Clyde Thomason says.

Impossible. The houses have been paid off for years, and Brooklyn is a control freak about paying her taxes as soon as possible. It must be a joke, a mistake.

Clyde says he’s already called the city. He was told the houses have both been sold, something about a third-party transfer of title. They have a week to move, or marshals will throw them out.

Brooklyn reads the eviction letter. Her home’s been stolen, sure enough, and the thief’s name is on the notice: the Better New York Foundation.

This Week’s Metrics

Mind the Gap: No trains this week; the infrastructure that matters this time is real estate.

What’s Cyclopean: The Enemy’s spider-things are covered by tiny mouths: “weird little holes like the thorns of roses turned inward.” Though lest this poetic language make It feel too smug, the comparison to “a sack of infinitesimal Legos” is also vivid.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

I’m writing this commentary on the road back from Worldcon in Chicago, where I attended several panels on urbanism and the future of cities. Speakers like Annalee Newitz (author of Four Lost Cities) and Arkady Martine (author of A Memory Called Empire and also a sustainability planner in New Mexico) brought passionate, high-level geekery to the question of what makes cities special even when they aren’t embodied in human form to fight elder gods. Quoth Newitz: “The archaeological record shows that cities are great places to party.”

She wasn’t being facetious: the density and energy of people, and the talent they bring, means that cities are going to have the biggest festivals, the best music, the most enticing dance floors. For the same reasons, they’re also hubs for information and trade and every other type of human exchange that multiplies our dimensionality. From that perspective, Brooklyn is a perfect city avatar: a hub of both partying and community organization, for whom this new role is “just the literalization of something she’s always done.” Earlier, she feared being dragged back to an earlier version of herself—now she imagines those different selves integrated. The natural resilience of a Brooklynite to change, or mental nudge on the part of the city-as-a-whole? Either way, impossible without her years of multifaceted experience.

Those integrated selves are badly needed: New York’s defense is going to need multiple layers. On the level of pure magic, music is always an enticing metaphor. Bardic magic is as old as stories themselves, and magic that hangs on the defiant beat of modern genres is as old as urban fantasy. Emma Bull’s War for the Oaks featured Minneapolis rockers Cats Laughing fighting the fae. MC Free is worthy not only of that inheritance, but of the older freestyle tradition of bards extemporizing lyrics. Think Lord of the Rings, where one of the things that makes Aragorn kingly is his talent for spur-of-the-moment odes to the dead. Or the “oldest game” featured in Sandman; rap battles are the closest modern-day equivalent.

But the Enemy doesn’t fight only with magic that can be dramatically (and quickly) repulsed. It’s also perfectly happy to leverage the inhuman, uncaring forces native to our universe. Bureaucracy, misused, can erase truth and identity as swiftly as glowing eldritch spiders that delete New-York-ness at a touch. I can only hope Brooklyn’s community organizing experience is as effective against an eviction notice as her bardic experience is against the spiders.

Or if not her skills, those of her fellow avatars. It’s easy to see, this chapter, why New York needs so many. On a symbolic level, they embody the many truths that make the city a nexus of realities: newcomer and lifelong tenant, old and young, multi-gender and multi-ethnic. On a practical level, they bring a range of skills and experience to the city’s defense. But this week, I find myself questioning why this multiplicity is unique to New York. Sure New York is special (my parents are from New York, of course I think it’s special) and has five official sub-cities, but that layering of realities—we learned last time—is what makes cities wake up in the first place! Shouldn’t DC have a homeless Street Sense editor and a think tank wonk and a newbie congress-critter? Shouldn’t Boston be represented by an introverted Harvard librarian and a Red Sox fanatic screaming Dropkick Murphys lyrics? No number of avatars short of “everyone” would actually feel like enough, but I don’t see how it’s a one-person job under any circumstances.

Arkady Martine says that all cities feel, to those who live in them, like the center of the universe. If that feeling—like the city has its own unique personality and yet incorporates millions of contradictions—is universal, maybe avatar-ship is always a compromise. It doesn’t seem like it could work any other way.

Anne’s Commentary

A couple chapters back, Brooklyn confided in Manhattan that her teenage daughter was getting to be a handful. In this chapter, their mother-daughter interaction reassured me that the bond between them is tight, the more so because both are strong-willed, keen-minded and drawn to community service. Jojo affects cool indifference to mama’s concerns, but Brooklyn knows it’s affectation; for example, Jojo has lost a favorite public school teacher to a “tony private school in Westchester,” prompting her support for a program to help teachers get affordable city housing. She’s also willing to do some uncool star-gazing with mama out their bedroom windows. The scene’s no space-filler. With admirable conciseness, it establishes why the threat to her family shakes Brooklyn so profoundly, compelling her into a spectacularly effective counterattack.

Brooklyn’s sphere of belonging radiates far beyond her relatives. After her first battles against the Enemy, she comes home to “this block that is hers and to these buildings that are hers in this borough that is so much hers that deep down she would’ve been surprised if someone else had gotten the job of becoming it.” Such expansive caring enables—perhaps entitles—her to embody millions of people and all the real estate on all the square mileage that comprises Brooklyn the place, the space.

Exposed during her fight to “the entirety of New York,” Brooklyn’s tempted only momentarily to lay claim to the whole city. Conversely, by whatever hunger entitles him to be Manhattan, Manny acknowledges no boundaries. His sense of self, and thus of his proper avatar-sphere, is shaky. It’s not surprising, given his memory loss, but the memory loss itself is no accident. It’s an essential feature of Manhattan, where so many go to lose previous lives. A certain greed is also an essential feature for the borough that attracts so many who want it all.

As a monster-maker, Jemisin is proving herself a very Abhoth, and I mean this in the best way, even though the H. P. Lovecraft Wiki describes this Clark Ashton Smith creation as “the Source of Uncleanliness,” a “horrid dark gray protean mass” said to spawn all the “miscreation and abomination” in the universe. Chapter Eight introduces “X-spiders,” easy shifters between at least two spatial dimensions with a tiny central body and four cylindrical limbs. Their mode of locomotion is to contract themselves into single lines and then “scissor out” into an X-shape again. This description makes me think more of a particular insect family than of spiders. That’s the Gerridae, whose many common names include pond skaters, water striders, water scooters, and water skimmers. If you’ve ever hung around ponds or streams, you’ve probably seen these guys darting around atop the surface rather than submersed in it. Being insects, they have six legs, but the first pair have modified into claw-like appendages; the other two pairs are long “oars” that give them the look of a flexing X. I like how they suspend themselves between air and water as they scoot in search of hapless bugs floating on the surface — in spite of their delicate appearance, these are predators.

So, too obviously, are the X-spiders, which can suspend themselves between dimensions via legs boasting lots of toothy mouths instead of hydrophobic hairs. Brooklyn proves right in thinking of them as “spiders” in that these beasties spin webs. Maybe we can call them hemipedal spiders, in that they have half the number of legs as earthly ones. [RE: Assuming the other half aren’t… elsewhere.] I wonder if the Enemy’s minions are creatures from its home dimension, perhaps somewhat mirroring earthly forms, or whether the Enemy shapes its minions after earthly forms as an extra bit of mocking fun.

The monsters this Enemy deploys are damn scary, but as Chapter Eight closes, Brooklyn and family are hit with something even scarier: the real-life terror of eviction. A cynical “admirer” of our species, the Enemy has learned how to manipulate human slaves to devastating effect. Bronca and her colleagues are deeply shaken when the Enemy deploys racist trolls against the art center. Are borough avatars able to shelter in their own home-spaces? Then the Enemy will have to flush them out into the open. It lures Padmini with the monster in Mrs. Yu’s pool. It lures Brooklyn into the unprotected half of her property with the X-spiders, but when she’s able to cast contamination-scouring protection not only on her own buildings but on the whole borough, the Enemy isn’t long daunted. It’s made “allies” in city hall and puts human bureaucracy (and political corruption) to use. For the Brooklyn who has fought to make a secure home for her family and who has meticulously paid all her bills, what could be a sharper blow than an eviction notice? It’s an insult added to the injury of losing her safe space, undermining who she is.

I looked up “third party transfer” and found a link to this NYC government page. The gist is that if a property has “significant delinquent municipal charges and poor housing conditions” that cannot be resolved, the city can foreclose on the property and transfer ownership “directly to a non-profit organization.” In a final slap to Brooklyn’s face, the non-profit third party in her foreclosure is “the Better New York Foundation.” Another quick search, and I find a real-life Association for a Better New York and a real-life New York Foundation. Could Jemisin’s non-profit be a fictional amalgamation of the two?

Brooklyn’s buildings are not in poor condition, nor has she failed to pay municipal charges, but if there are Enemy-controlled people with access to city records, she’ll have to fight to foil the eviction—a fight that she’ll either lose, or that will fatally distract her from the main battle for New York.

Either way, that wily Woman in White scores big-time!

Next week, join us for Tananarive Due’s “The Wishing Pool,” the first addition to our reading list from Ruthanna’s extensive (and still somewhat disorganized) Worldcon notes!

Ruthanna Emrys’s A Half-Built Garden is now out! She is also the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her short story collection, Imperfect Commentaries, is available from Lethe Press. You can find some of her fiction, weird and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.