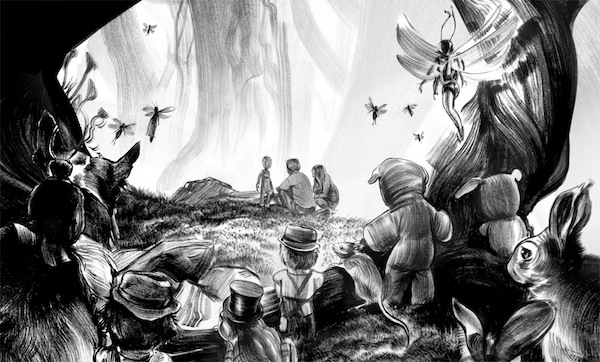

One of the core reasons I make books now is because Ray Bradbury scared me so happy, that what I am perpetually compelled to do is, at best, ignite the same flame in a young reader today. Most of my comics, certainly the ones I write myself, are scary ones or revolve around scary themes. At some point I began to notice that they also featured, as protagonists, children. Even when the overall story wasn’t necessarily about them, there they were: peeking from behind some safe remove, watching.

I came to understand the pattern was leading me to a more clearly defined ethos when I both had kids of my own and I came to find that the comics industry had for the most part decided not to make books for kids anymore. Instead they wanted to tailor even their brightly colored, undies-on-the-outside superhero books to old men nostalgic for their long-passed childhoods than for the children they were intended to inspire. Insane, right? This generation had not only stolen the medium away from its following generations, it had helped foster one of the greatest publishing face-plants in American history: it killed its own future by ignoring the basic need to grow a new crop of readers, and so made certain it had no future at all.

And one thing no one was going near was horror stories for kids. So it was time to do what the big publishers wouldn’t: scare the hell out of kids and teach them to love it. Here’s why this is not as crazy as it sounds:

Reason #1: CHILDHOOD IS SCARY

Maurice Sendak, whom I love as a contributor to the lore of children’s literature as well as a dangerous and wily critic of the medium (especially in his grouchy latter years), once countered a happy interviewer by demanding she understand that childhood was not a skip-hop through a candy-cane field of butterflies and sharing and sunshine, that is was in fact a terrifying ordeal he felt compelled to help kids survive. Kids live in a world of insane giants already. Nothing is the right size. The doorknobs are too high, the chairs too big… They have little agency of their own, and are barely given the power to even choose their own clothes. (Though no real “power ” can ever be given, anyway… maybe “privilege” is the right term.) Aside from the legitimate fears of every generation, kids today have witnessed these madhouse giants lose their jobs and their houses, grow increasingly angry and divided over politics, blow themselves up using the same planes they ride to visit grandma, and catastrophically ruin their own ecosystem, ushering in a new era of unknown tectonic change and loss their grandkids will get to enjoy in full. The insane giants did to the world what they did to comics: they didn’t grow a future, but instead ate it for dinner.

It’s a spooky time to be a kid, even without the constant barrage of school shootings making even the once-fortified classroom a potential doomsday ride. Look, the kids are already scared, so let’s give them some tools to cope with it beyond telling them not to worry about it all… when they really have every right to be scared poopless. Scary stories tell kids there’s always something worse, and in effect come across as more honest because they exist in a realm already familiar to them. Scary tales don’t warp kids; they give them a place to blow off steam while they are being warped by everything else.

Reason #2: POWER TO THE POWERLESS

The basic thing horror does for all of us is also its most ancient talent, the favorite system of crowd control invented by the ancient Greeks: catharsis. Who doesn’t walk out of a movie that just scared the pants off of them mercifully comforted by the mundane walk to through the parking lot and the world outside? For kids this is even more acute. If we take it further and make children both the object of terror in these stories as well as agents for surviving the monsters…well, now you’re onto something magical. Plainly put, horror provides a playground in which kids can dance with their fears in a safe way that can teach them how to survive monsters and be powerful, too. Horror for kids lets them not only read or see these terrible beasts, but also see themselves in the stories’ protagonists. The hero’s victory is their victory. The beast is whomever they find beastly in their own lives. A kid finishing a scary book, or movie can walk away having met the monster and survived, ready and better armed against the next villain that will be coming…

Reason #3: HORROR IS ANCIENT AND REAL AND CAN TEACH US MUCH

In the old days, fairy tales and stories for kids were designed to teach them to avoid places of danger, strangers, and weird old ladies living in candy-covered houses. They were cautionary tales for generations of kids who faced death, real and tangible, almost each and every day. There was a real and preventive purpose to these stories: stay alive and watch out for the myriad of real world threats that haunt your every step. These stories, of course, were terrifying, but these were also children that grew up in a time where, of every six kids born, two or three would survive to adulthood. Go and read some of the original Oz books by Baum and tell me they are not freakishly weird and threatening. The Brothers Grimm sought to warn kids in the most horrifying way they could. So much so that these types of tales have all but vanished from children’s lit, because these days they are deemed too frightening and dark for them. But they also are now more anecdotal than they were then; they mean less because the world around them grew and changed and they remained as they had always been. They became less relevant, however fantastic and crazy-pants they are.

Horror also touches something deep within us, right down into our fight-or-flight responses. We have developed, as a species, from an evolutionary necessity to be afraid of threats so we might flee them and survive to make more babies that can grow up to be suitably afraid of threats, that can also grow up and repeat the cycle. We exist today because of these smart apes and they deserve our thanks for learning that lesson. As a result, like almost all pop culture, horror lit can reflect in a unique way the extremely scary difficulties of being a child in a certain time. It touches on something we all feel and are familiar with, and as such can reveal a deeper understanding of ourselves as we go through the arc of being scared, then relieved, and then scared again. The thrill is an ancient one, and when we feel it, we’re connecting with something old and powerful within us. Whether it’s a roller-coaster, a steep water slide, or watching Harry Potter choke down a golden snitch as he falls thirty stories from his witch’s broom. There is a universality in vicarious thrill-seeking and danger-hunting. It is us touching they who began the cycle forty thousand years past.

Reason #4: HORROR CONFIRMS SECRET TRUTHS

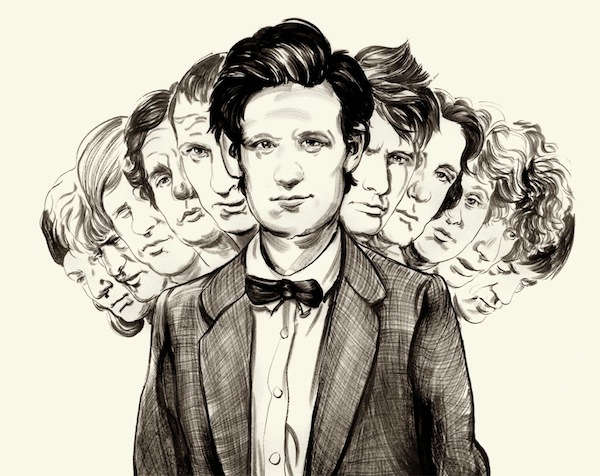

Consider this moment from “The Eleventh Hour,” the episode that introduced Matt Smith’s Eleventh Doctor to the world:

“You know when grown-ups tell you everything’s going to be fine and there’s nothing to be worried about, but you know they’re lying?” says the Doctor to a young, mortified Amy Pond. “Uh-huh ,” she replies, rolling her ten-year-old eyes dramatically. The Doctor leans in, a wink in his eye and intimates… “Everything’s going to be fine.” And then they turn to face the monster living in her wall with a screwdriver in one hand and a half-eaten apple in the other.

In doing this, writer Steven Moffat touches brilliantly upon another essential truth of horror—that it shows us guardians and guides that will be more honest with us than even our own parents. Within the darkness and shadows is our guide, who can lead us out and back into the light, but you can only find him there in the darkness, when you need him most. Kids are aware of so much more that’s happening in their house than we as parents even want to imagine. But because we don’t share all the details of our anxious whispers, stressful phone calls, or hushed arguments, (and rightfully so), they are left to fill in the facts themselves, and what one imagines tends to be far more terrible than what is real. They know you’re fighting about something, but not what. They can tell what hastened whispers in the hall mean outside their door…or they think they do. And what they don’t know for a fact, they fill in with fictions. Storytellers dabbling in horror provide them with an honest broker who doesn’t shy away from the fact of werewolves or face-eating aliens that want to put their insect babies in our stomachs. They look you straight into their eyes and whisper delightfully “Everything’s going to be fine.” The mere fact of telling these tales proves a willingness to join in with kids in their nightmares, bring them to life, and then subvert and vanquish them. Children love you for this, because you are sharing a secret with them they don’t yet realize everyone else also knows: this is fun.

The end result, for me, at least was a great sense of trust in scary movies I never got from my parents, who tried to comfort me by telling me ghosts weren’t real. Horror told me they were, but it also taught me how to face them. We deny to our kids the full measure of what we experience and suffer as adults, but they aren’t idiots and know something’s going on, and what we’re really doing by accident is robbing them of the trust that they can survive, and that we understand this and can help them to do so. Where we as adults cannot tell them a half-truth, horror can tell them the whole, and there is a great mercy in that.

Reason #5: SHARING SCARY STORIES BRINGS PEOPLE TOGETHER

How many times have I seen a group of kids discover to their excessive delight that they have all read and loved the same Goosebumps book? A LOT. The first thing they do is compare and rank the scariest parts and laugh at how they jumped out of their bed when the cat came for a pat on the head, or stayed up all night staring at the half open closet. Like vets having shared a battle, they are brought together in something far more essential and primordial than a mere soccer game or a surprise math test. And looking back myself, I cannot recall having more fun in a movie theater or at home with illicit late night cable TV, than when I was watching a scary movie with my friends. The shared experience, the screams and adrenaline-induced laughter that always follow are some of the best and least fraught times in childhood. And going through it together means we aren’t alone anymore. Not really.

Reason #6: HIDDEN INSIDE HORROR ARE THE FACTS OF LIFE

Growing up is scary and painful, and violent, and your body is doing weird things and you might, to your great horror, become something beastly and terrible on the other side. (The Wolfman taught us this). Being weird can be lonely and your parents never understand you and the world is sometimes incomprehensible. (Just as Frankenstein’s monster showed us). Sex and desire is creepy and intimate in dangerous and potentially threatening ways (so sayeth Dracula).

Whether it’s The Hunger Games as a clear cut metaphor for the Darwinian hellscape of high school, or learning to turn and face a scary part of ourselves, or the dangers of the past via any of the zillions of ghost stories around, horror can serve as a thinly-veiled reflection of ourselves in a way almost impossible to imagine in other forms. Horror can do this because, like sci-fi and fantasy, it has inherent within it a cloak of genre tropes that beg to be stripped off. Its treasures are never buried so deep that you can’t find them with some mild digging. It’s a gift to us made better by having to root around for it, and like all deep knowledge, we must earn its boons rather than receive them, guppy-mouthed, like babies on a bottle.

Fear is not the best thing in the world, of course, but it’s not going anywhere and we are likely forced to meet it in some capacity, great or small, each and every day. There’s no way around it. Denying this fact only provides more fertile ground for fear to take root. Worse yet, denying it robs us of our agency to meet and overcome it. The more we ignore scary things, the bigger and scarier those things become. One of the great truths from Herbert’s perpetually important Dune series is the Bene Gesserit’s Litany Against Fear:

I must not fear.

Fear is the mind-killer.

Fear is the little death that brings total obliteration.

I will face my fear.

I will permit it to pass over me and through me.

And when it is gone past I will turn to see its path.

Where the fear has gone, there will be nothing.

Only I will remain.

In so many geeky ways this sums up the most important and primary element of fear—not to pretend that it doesn’t exist, or whether it should or not, but to meet it, to hug it, and to let it go so we may be better prepared for whatever else comes next.

Crafting horror narratives for kids does require changing the way scary things are approached, but I would argue that what tools we are required to take off the table for a younger audience aren’t really important tools in telling those stories in the first place. Rape, gore, and splatter themes are terrible, deeply lazy and often poorly executed shortcuts for delivering weight and fear in a story. Losing them and being forced to employ more elegant and successful tools, like mood, pacing, and off-camera violence—the sorts of things one must do to make scary stories for kids—make these tales more interesting and qualitative, anyway. We are forced to think more creatively when we are denied the alluring tropes of the genre to lean on. We are more apt to reinvent the genre when we aren’t burdened by the rules all genres lure us into adopting. With kids, one must land on safer ground sooner than would be the case with adults, but otherwise what I do as a writer when I tell a scary story to kids is essentially the same thing I would do to craft one for adults. There are certain themes that require life experience to understand as a reader, as well, and a successful storyteller should know their audience.

Don’t be afraid to scare your kids, or your kids’ friends, with scary books you love. Obviously you have to tailor things to your kids’ individual levels. For example, films and books I let my 11-year-old digest, I won’t let my younger boy get into until he’s 14. They’re just different people and can handle different levels of material. They both love spooky stuff, but within their individual limits. Showing The Shining to an 8-year-old is generally a poor idea, so my advice is when there’s doubt, leave it out. You can’t make anyone un-see what you show them, and you should be responsible as to what they are exposed to. I’m a bit nostalgic about sneaking into to see The Exorcist at the dollar cinema way too young, but I also remember what it felt like to wake up with twisty-headed nightmares for a month afterward, too. Being scared and being terrorized are not the same thing. Know the difference and don’t cross the streams or it will totally backfire on you. But if you navigate it right, it can be a completely positive and powerful experience.

So get out there and scare some kids today! Do it right and they’ll thank you when they’re older. There will be a lot of adults who find this whole post offensive and terrible, even as their kids cry for the material… I remind them that children are often smarter than the adults they wind up becoming. The parents that find this so inappropriate are under the illusion that if they don’t ever let their kids know any of this stuff, they won’t have bad dreams or be afraid—not knowing that, tragically, they are just making them more vulnerable to fear. Let the kids follow their interests, but be a good guardian rather than an oppressive guard. Only adults are under the delusion that childhood is a fairy rainbow fantasy land: just let your kids lead on what they love, and you’ll be fine.

All images by Greg Ruth.

An earlier version of this article was originally published in May 2014 on Muddy Colors.

Greg Ruth is a New York Times Bestselling author of The Lost Boy and has worked making books and comics and illustration and design work for film since 1993. He is published through The New York Times, Toho, DC Comics, Fantagraphics Books, Caliber Comics, Marvel, Dark Horse, HarperCollins, Macmillan,Hyperion, Simon and Schuster, Random House, Slate, CNN, Lionsgate, Warner Brothers, Legendary, AppleTV, Netflix, Penguin, MONDO, Politico, NEON, Variety, and Tor. He has created two music videos for Prince and Rob Thomas, designed and illustrated LPs for Dune, Severance, Godzilla, Marvel, and HBO. Greg has also created work for nearly a dozen children’s picture books including Our Enduring Spirit (with Barack Obama), Red Kite, Blue Kite (with Ji Li Jiang), A Pirate’s Guide to First Grade and A Pirate’s Guide to Recess (both with James Preller), and Coming Home, which he wrote and illustrated. His comics work includes Conan: Born on the Battlefield (with Kurt Busiek), Freaks of the Heartland (with Steve Niles), Sudden Gravity, The Lost Boy, The 52 Weeks Project, The Matrix Comics, Goosebumps with R.L. Stine, and Indeh and Meadowlark with Ethan Hawke. Greg lives and works in Western Massachusetts.