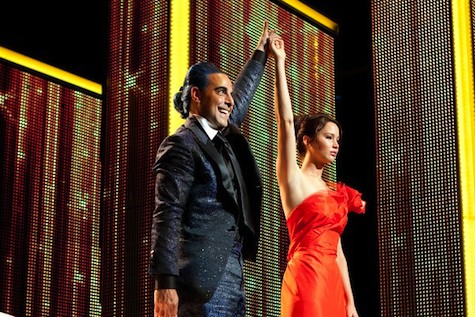

The Hunger Games has come and gone, and the world has called for more heroes like Katniss Everdeen, the proof that Hollywood had been waiting for: a female protagonist who carried a blockbuster movie and made bank at the box office. Katniss is now heralded as the hot new thing in fiction and film, the one-of-a-kind that the world needs more of. In response, The Atlantic wrote up its list of female YA heroes (not all who were accurate to the title) of bygone years to point out that Katniss herself was not an anomaly. Right here on Tor.com, Mari Ness discussed the girl heroes that were missed, and the many stories that are often taken for granted in this arena.

But here’s a weird thought… what about female heroes for grown ups?

A little background from the perspective of my own readings habits just to make a point. As a child, I read books that would probably be labeled as “YA” from the ages of seven to nine with a few exceptions when I got older. A pretty small bracket for a genre that is currently the darling of the publishing world, but it was a bit different before Rowling, I’d say. I jumped to Star Wars books, and then abruptly into adult fiction of all sorts. I read Douglas Adams, and Ray Bradbury, and Frank Herbert, and loved every minute of it.

And on the playground, when my friends and I pretended to be other people, I pretended to be boys.

But this is not about being a geeky little girl, or even being a tomboy (I think the term was applied to me once or twice, but I don’t think it was particularly apt in my case). This is about the confusing place that many girls find themselves in when they realize that all those fun lady heroes they grew up with just plain vanish once they reach adult and pop fiction narratives.

But what about Ripley? I know, there are examples here and there of female characters who take up that ring or big damn gun or quest and run with it into their own proverbial sunset (or don’t). But they’re still far from the norm in fiction. And, more importantly, there are certain types of characters who are practically never written as women. Captain Jack Sparrow. Ford Prefect. Loki. Jonathan Strange. Gandalf. In fact, that’s a whole other dilemma, but one that still demands investigation.

Lisbeth Salander of The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo is a hero of pop fiction, some might say. But how many women only become heroic figures due to terrible trauma in their lives (that are usually rape and/or physical violence)? Salander is the poster child for this sort of female character-building, the kind that films like Sucker Punch have capitalized on to their own overblown, outrageous conclusions.

It’s not that we should do away with narratives where women overcome abuse at the hands of men; those are important stories in their own right. But that’s not the sort of hero that every woman is looking for. Maybe she’d like a woman who is trying to overcome fear, or indolence, maybe she would like to see someone who is coming to terms with a Great Destiny. Maybe everyone would like to see that.

Now, there are usually token female figures in fictional universes dominated by men, so at least women have someone to latch onto—they aren’t excluded entirely the way minorities often are. Star Wars has Princess Leia and Mara Jade, Harry Potter has Hermione and Ginny, Lord of the Rings has Eowyn, and there are countless others. But what is that telling the world exactly? It’s entirely possible that many fans who complain that the Harry Potter books should bear Hermione’s name instead are reacting to this very trend, the insistence that women are never the central figures no matter how much know-how, bravery, and fortitude they contribute to a story.

Moreover, the lack of these figures in popular adult fiction sends a hard and fast message to female readers and viewers: that once you grow up, you graduate to adult books and adult characters—and they are men.

Lady heroes? That’s kiddie play.

I didn’t always pretend to be male characters. When I was very small, I would sit in my room and imagine that I was Tinkerbell, Dorothy, Harriet the Spy and Annie Oakley. And then I got a little bit older and all of that ended. I wanted to be the bigtime hero, not a sidekick, princess, girlfriend, or best pal. I wanted to be the plucky, comic pain in the butt. Even better, I wanted to be the villain! (And preferably one who was not evil just because her step-daughter turned out to be prettier than she was.) But there were so few examples for me to draw on that I spend a solid year trying to be Luke Skywalker instead. That doesn’t mean I’m the beacon of normalcy that people should set their compasses by, but I highly doubt I was the only little girl who took a similar route. It’s almost sure to be one of the reasons that genderswapped cosplaying has become so popular over the years.

We’re perfectly happy to let women rule YA fiction, and authors in the genre are frequently praised for creating such interesting characters for girls to emulate and learn from. These stories are so engaging that they have a crossover appeal; there are plenty of adults who read YA fiction and they are perfectly happy doing so. I thoroughly enjoyed the Hunger Games trilogy myself. But here’s a question no one is asking is it possible that the reason for YA’s popularity amongst an older crowd is in part due to the fact that there are so many female protagonists to chose from? Are we running toward the genre with our arms wide open because we see something that we want and don’t find elsewhere?

I think the question is too pressing to ignore.

And what if it was a question that we were willing to tackle with a bit more proactivity? I understand the attraction in writing coming of age stories, but wouldn’t it be spectacular if the next major adult epic fantasy series had a female hero at its heart? If the newest superhero to take off was Batwoman or Ms Marvel? What if the biggest television show since LOST was cancelled had a killer lady antagonist?

Katniss Everdeen is an excellent female hero. But she and Ripley and Buffy need to be eclipsed by more characters who live up to their calibre.

Emmet Asher-Perrin really wants a lady superhero movie to make all the money. You can bug her on Twitter and read more of her work here and elsewhere.