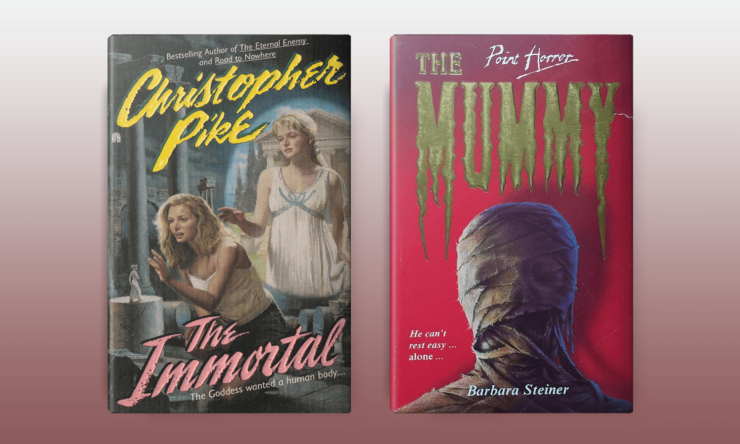

The everyday lives of the guys and girls of ‘90s teen horror seem complicated enough, full of secrets, betrayal, murder, and (occasionally) monsters. But when these dangers feel just a bit too prosaic, there are always evils from the past that can resurface, synthesizing ancient civilizations and terrors with the teens’ modern existence. Christopher Pike’s The Immortal (1993) and Barbara Steiner’s The Mummy (1995) connect their young female protagonists to these past lives, with ancient Greece in The Immortal and ancient Egypt in The Mummy. These connections with and explorations of concerns much larger than themselves reveal these girls to be just one small piece of a much larger picture, as well as lending an air of exceptionalism: the young women who are connected to these past lives are special, chosen, and bigger than the petty dramas of the contemporary moment in which they live.

In Pike’s The Immortal, Josie Goodwin is on vacation in Mykonos with her father, his girlfriend, and Josie’s best friend Helen Demeter (names don’t get much more Greek mythology-infused than that!). Josie and Helen are having the time of their lives, zipping around the island on motorbikes, checking out the nude beaches, and spending time with a couple of hunky fellas, Tom and Pascal, who come to the island to work during tourist season. Despite these distractions, Josie finds herself powerfully drawn to Delos, an island of ruins not far off the coast of Mykonos. While this is supposed to be a free and easy vacation, celebrating the girls’ high school graduation, the group has a lot more baggage than their carry-ons: Josie’s father is a screenwriter, though he’s suffering a bad case of writer’s block. Josie resents her father’s girlfriend, who she thinks is just using her dad to get her foot in the Hollywood door. Josie and Helen have both suffered fairly recent traumas, with Helen attempting suicide and Josie having a cardiac episode on the exact same day the previous summer. And while Josie and Helen are supposedly best friends, that didn’t stop Josie from stealing Helen’s boyfriend Ralph and now, seducing Tom even though she knows Helen really likes him. But Helen seems to have an inexplicable inside track, having vacationed in this exact same spot as a recuperative getaway following her suicide attempt. She uses this familiarity to manipulate and manage Josie, including taking her to Delos, and feeding her friend’s growing obsession with the island and the gods commemorated there.

As Josie falls further under the spell of Delos, she begins to access memories that are not her own, dreaming of a goddess named Sryope, “the daughter of Thalia, muse of Apollo” (104). Sryope’s life and emotions are intimately familiar to Josie, with the resonance of recollection rather than dream. Following the signature Pike approach of nesting a story within the larger story, three long chapters interspersed throughout the novel bring Sryope’s story to the forefront: Sryope had a dear friend named Phthia, a fickle lover who claimed the heart of a young demigod (son of Aphrodite and a mortal father) named Aeneas; in the throes of their passionate romance, Phthia demanded that Aeneas make a vow of fidelity that he would never love anyone else, but Phthia herself soon tired of him and moved on to other lovers. When Sryope and Aeneas fell in love, Sryope—a legendary storyteller—challenged Phthia to a storytelling contest to free Aeneas from his vow, regaling the gathered crowd with a tale that fictionalized Phthia’s own story and the shameful secret that her father was one of the legendary Furies, a secret Sryope had promised never to tell. Enraged and embarrassed (even though Sryope didn’t technically break her promise or reveal her friend’s gossip-worthy lineage), Phthia fled, and Sryope and Aeneas were free to marry. And all was well(ish) until Sryope was accused of meddling in the affairs of mortals—specifically, Josie and Helen—and sentenced to live the rest of her life in a mortal body.

Buy the Book

Witch King

There are significant parallels between the story of Sryope and Phthia and that of Josie and Helen, of course, in the young women’s betrayal of one another, their fractured friendship, and the men over whom they compete and quarrel, with Ralph and then Tom taking the place of Aeneas. And really, this is just as it should be, because these two young women really are Sryope and Phthia, with the girls’ human bodies serving as vessels for the ancient Greeks after the girls themselves died, Helen from an overdose and Josie from a cardiac episode, both of which were orchestrated by a meddling Fury. The lives Josie and Helen have thought they were living for the last year have been nothing but an illusion, though it takes them awhile to realize who they really are and what this means for the teen lives they have now irretrievably lost. It seems unfair that they should have to die twice—Helen killing Josie by putting ground glass in her food and Josie shooting Helen to save her friends—but they do, to balance the cosmic scales of the two girls who have died but still live, and to expel the spirits of Phthia and Sryope.

Through the synthesis of Josie’s consciousness with that of the goddess Sryope, she comes to understand the divine nature of humanity itself. In her final moments on Earth, Sryope reflects that in looking at Josie and her life from Sryope’s elevated position among the gods, “I had watched the images and thought how fine the young mortal was—for a mortal. Now I knew she had been divine before I entered her body” (207). Josie’s humanity is her greatest weakness but it is also what makes her perfect, on par with the gods themselves. Josie may die, but her spirit will live on and when Josie/Sryope leave the world behind, it is only “For now” (209), with the explicit promise of reincarnation and return.

Reincarnation is central to Lana Richardson’s experiences in The Mummy as well, though luckily Lana doesn’t have to die to tap into this awareness of interconnection and return. Lana is obsessed with ancient Egypt: she learns everything she can about it, has decorated her room in Egyptian style, and even has her hair cut to resemble that of an ancient Egyptian princess. So when a display of Egyptian antiquities, including the mummy of Prince Nefra, are going to be exhibited at her local museum, she becomes a volunteer, guiding tours and gaining invaluable experience for her dream of one day becoming an archeologist. This also gives her the opportunity to get to know and work with Blair Vaughn, a formidable woman and renowned archeologist, though Blair remains cold and distant toward Lana, with this mentorship not turning out to be all that Lana dreamed it would be.

Almost immediately, strange things begin happening at the exhibit: the lights go off while Lana is in the room with Prince Nefra’s mummy (though they stay on everywhere else in the museum) and Lana feels a sense of warmth and well-being in Prince Nefra’s presence. Prince Nefra begins calling to Lana, whispering for her to “Come to me! You are mine. You must come to me!” (10). She encounters a threatening mummy in the fog on her walk home one night, somebody drops scorpions through her window, a priceless emerald necklace is stolen from the exhibit, and not one but two volunteers find themselves attacked and trapped in sarcophagi.

Much like the ancient Greek story in The Immortal, love is at the center of the unrest: Prince Nefra was preparing to marry his beloved Princess Urbena, for whom the emerald necklace on display was a wedding gift. However, right before Nefra and Urbena’s wedding, as the story goes, “Nefra was murdered and then Princess Urbena committed suicide” (13). This is all conjecture, reconstructed from surviving evidence and artifacts, and no one really knows what happened or what the motive for Price Nefra’s murder might have been. Lana feels a strong bond with Princess Urbena and may have the ability to tap into the princess’s memories and emotions, and while historical speculation is that Princess Urbena’s mummy was entombed with Prince Nefra’s and later stolen, Lana’s visions suggest that Princess Urbena was murdered as well, attacked and buried alive, never entombed with Prince Nefra in the first place. While this remains unverifiable and Steiner leaves Lana’s impressions more open to interpretation than Pike does in The Immortal, Lana does have a clear connection and sensitivity to the energies of the Egyptian artifacts on display and particularly to the mummy of Prince Nefra, which continually draws her, and some of her experiences really do seem to be supernatural in nature.

The theme of romance and attraction spills out from the ancient Egyptian narrative into Lana’s everyday life as well. Lana has a boyfriend named Josh, who is handsome but kind of a jerk. He and Lana don’t have much in common and he repeatedly tells her that he thinks her interest in ancient Egypt is boring and a waste of time. When there’s a big costume party at the museum to commemorate the close of the exhibit, Lana dresses in a handmade period gown and Josh wraps himself in toilet paper. But there are a couple of attractive guys on her radar at the museum, including a young Egyptian man named Antef Raam, who traveled to the United States with the exhibition, and Rodney Newland, who had lived overseas in Egypt. Both of these young men are more interesting than Josh and have more in common with Lana, sharing her passion for Egypt and archeology, and while she has mild flirtations with both of them—not to mention a strong romantic attraction to Prince Nefra—Lana inexplicably chooses Josh time and again. It’s great to have passionate and exotic interests, as long as you have some status quo romance safety net to fall back on, it seems. Lana’s long-term goal is to become an archeologist, even though she knows it’s going to take a lot of hard work, the competition is fierce, and the job prospects are pretty dismal, and it’s hard to imagine Josh being a supportive partner as she chases this dream. With Lana’s goal and her clear commitment to achieving it in mind, Josh might be less Mr. Right and more Mr. Right Now, the comforting, familiar, and expected boyfriend before Lana’s real life gets started, which feels a bit less dead end-y, but is still kind of a bummer. When a guy tells you the things you love are dumb, he’s got to go.

Lana eventually discovers that Antef is the one who stole the necklace and trapped her in the sarcophagus, though he wasn’t acting alone. Blair Vaughn, the archeologist who Lana has been looking up to and whose career she hoped one day to emulate, is the mastermind behind the theft of the emerald necklace and most of the other spooky goings-on at the museum. Blair believes that the necklace is cursed and that this curse is responsible for a series of misfortunes that have fallen upon her family. As she tells Lana, “You are Urbena, you know you are. And if I could have returned you to Egypt and the tomb, my family would stop dying … The curse will go on and on unless I can return Urbena’s mummy. You were perfect” (202). Blair’s superstition and hysteria are further compounded, and she is completely discredited, when it turns out that her version of her father and grandfather’s deaths and her sister’s disappearance is a deeply flawed conspiracy theory and obsession, rather than the murders and abductions she has claimed them to be.

As the exhibit opened, Lana was thrilled at the possibility of working with one of the women she looked up to, a model of who she could be and the career she could have if she followed her dreams, but in these closing moments, that dream is revealed as a nightmare and Lana is left to forge her own path and figure it out on her own.

The most fascinating element of The Mummy—and the one that seems to most clearly indicate that at least some of the supernatural occurrences and the feeling of reincarnation Lana experiences throughout the novel are true—is Lana’s black cat, Seti, who shows up on her doorstep as a stray just as the exhibit is set to open. Seti is a striking cat, who on being taken into Lana’s home “sat tall and regal, looking exactly like one of the ebony statues in the exhibit. Lana reached out for him, but he stepped back, as if to say, don’t bother me, I’m busy doing my king-of-the-household look. Just look and worship me” (20). He is also the MVP of The Mummy: he begins meeting Lana when she gets off work at the museum to walk home with her, and he defends her from the mummy they encounter in the fog (Blair in disguise). He is kidnapped as part of a plot to terrorize Lana, but escapes and triumphantly returns to Lana’s side. When Lana is trapped in the sarcophagus, Seti comes to her rescue, scratching at the top until the humans make themselves useful and set Lana free. Blair is terrified of Seti, believing him to be the reincarnation of Prince Nefra, which gets a little complicated (is Nefra’s spirit embodied in the mummy, who Lana has heard calling to her? In Seti? Both? Is Blair’s belief that Seti is Nefra another flawed perception on her part, as established by her larger beliefs about the curse?). But one thing is for sure: when the exhibit goes, so does Seti. As he goes to Lana’s window to be let out following the final night of the exhibit, “Seti paused in the window and looked at Lana for a long time … He wore that look she was sure was a tiny smile. She saw and felt the love in his eyes. And she returned that love” (208-209). While the truth is impossible to pin down—just like the speculations about Prince Nefra and Princess Urbena that run throughout the book—Lana knows Seti “was like no other cat. Of that she was sure” (209). Given all the terrible things that can happen to a cat on its own (and particularly a black cat, which are frequently targets of superstition and violence), the idea that Seti was linked to the exhibit and is safely on his way back to Egypt is the happiest possible ending for him, which—in this cat lover’s humble opinion—is a pretty compelling reason to suspend one’s disbelief and just accept that Seti is a wise, supernatural being.

In both The Immortal and The Mummy, Josie and Lana find themselves connected with something much larger than themselves, a part of epic romances that have spanned thousands of years. Their lives are touched and shaped by powerful women who came before them, whose influence reaches into the present moment. Just as Sryope and Urbena’s power endures long after their mortal lives have ended, Josie and Lana are forces to be reckoned with, writing their own history and legends even as they live them, strengthened by drawing on the larger-than-life figures of these women from the past. For Josie, the promise of reincarnation is central to her path forward, though this remains grounded in the remembrance and telling of her own story, as Pike closes the novel with Sryope telling Apollo that “I do have a story to tell. It starts with this girl on a plane” (213), taking readers back once more to The Immortal’s opening chapter. The Mummy is a bit more optimistic in its next steps forward, as Lana will presumably keep following her dream of becoming an archeologist. Lana doesn’t have to die and be reborn, though just like Josie, the question of rebirth is on her mind in the book’s final lines, where she tells the spirit of Prince Nefra that “I’m sorry I couldn’t return with you this time. But maybe, someday, I will know you again” (210). Reincarnation, repetition, and return are central to both The Immortal and The Mummy, regardless of where their protagonists end up at the end of their respective journeys. This promise of reincarnation not only establishes Josie and Lana as part of something larger than themselves, but offers the reassurance that their own stories will never really end.

Alissa Burger is an associate professor at Culver-Stockton College in Canton, Missouri. She writes about horror, queer representation in literature and popular culture, graphic novels, and Stephen King. She loves yoga, cats, and cheese.