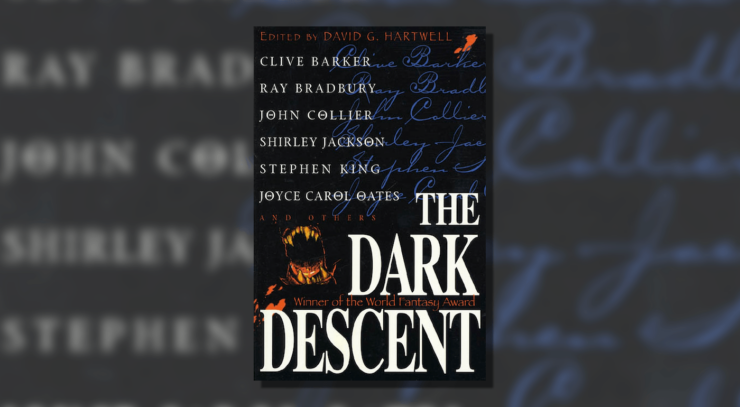

Welcome back to Dissecting The Dark Descent, where we lovingly delve into the guts of David Hartwell’s seminal 1987 anthology story by story, and in the process, explore the underpinnings of a genre we all love. For an in-depth introduction, here’s the intro post.

Montague Rhodes James is perhaps one of the more important figures in horror. A folklorist, antiquarian, and writer of short Gothic horror stories, he’s responsible for discovering multiple buried pieces of English history, as well as furthering interest in J. Sheridan Le Fanu’s work (he even edited a collected edition of Le Fanu’s stories entitled Madam Crowl’s Ghost). Perhaps most relevant to this piece, James also wrote volumes of horror criticism and produced a prolific bibliography of short horror stories—his work was even adapted into a BBC special featuring the dulcet tones of Sir Christopher Lee—meant to critique Gothic fiction while bringing the work into a more modern time and place.

In this way, James was one of the earliest to adopt the “modernist” style of horror stories, exploring more “traditional” ideas and monsters through a much more modern lens. “The Ash Tree,” Hartwell’s selection from the James canon, might not be set in a modern time, but its re-framing and inversion of the traditional story of generational curses, occult practices, and disturbing vegetation could sit alongside present-day explorations of the genre. It also manages to be a perfect discussion of the “moral allegorical” tone of horror, bringing more (for James’ time) present-day morality to a story involving the witch trials.

But while all that’s well and good, let’s dive into the summary for those who haven’t had the pleasure yet. In the 1600s, during the most intense phase of England’s mass hysteria over witches, Sir Matthew Fell, lord of Castringham Hall, testifies against his neighbor Mrs. Mothersole, whom he sees at night murmuring and cutting branches off his ash tree. Thanks to him, Mothersole is promptly tried as a witch and, despite the protests of Fell’s fellow townsfolk, hanged by Fell, who is also the Deputy-Sheriff of Suffolk. As revenge on her nosy neighbor, Mothersole utters a terrifying pronouncement upon her execution: “There will be guests at the Hall.” This prophecy of doom kicks off an unnerving series of events beginning with Fell’s death and a curse that stretches generations, all tied to the foreboding ash tree located outside Sir Matthew’s window. For, invited or no, he and his descendants have guests at Castringham Hall.

What makes “The Ash Tree” truly interesting is the way James uses his knowledge of gothic tropes and clichés to form a more original and modern work. The portents of doom are incredibly straightforward, much of the narrative takes place in broad daylight, and there’s an entire section of the story where no one goes into the cursed bedroom by the ash tree, leading to a member of the supposedly cursed family line dying of natural causes while his livestock die unnaturally instead. At times, there are even flashes of dark comedy. One such moment involves the local vicar consulting his Bible at random as a method of divination, getting clear instructions, and then promptly chalking the first Castringham’s mysterious death up to an assassination plot by Catholics in his Sunday service.

Even the setup is steeped in modernity and subversion. James spends part of his exposition writing a subdued but appropriately bitter indictment of witch trials, and the curse begins when a well-liked and influential woman (with actual occult powers) is killed by a town official who does it mainly because his neighbor was annoying him. It’s a much more modern take on the idea of “moral allegory.” While Mrs. Mothersole’s actions are certainly a trifle strange, nothing she does until after her execution is particularly malicious, and all the occult malice is entirely justifiable, since her neighbor got her officially executed just for acting odd on his property and trespassing (Was Sir Matthew an early version of an HOA? Please let me know in the comments). James extends his moral calculus to systemic evil itself— the murder and subsequent occult executions only happen because everything in the system does exactly what it’s supposed to, and the Widow’s spirit is only balancing the books. This even extends to those who band together to finally take down the titular tree, who are a group of townspeople and servants— the curse is finally broken because it kills something it’s not supposed to, and the tree is destroyed by the town banding together as a result.

While it’s gleefully subversive, “The Ash Tree” is still extremely effective. Any humor is grim and relayed in deadpan fashion. The idea of the curse (which causes grotesque bodily deformations, can poison people who touch affected corpses, and apparently drains blood) is shudder-inducing to think about. More than that, the idea of a system so apathetic that it allows for murder, seen by the universe as something it has to correct. Understanding a genre isn’t just about knowing what clichés to twist or what tried-and-true ideas to subvert—it’s about what you keep. Gothic fiction is known for a sense of foreboding and doom that extends to the environment, and James plays this to the hilt.

Buy the Book

Maeve Fly

As the story ramps up to its climax, he even sprinkles in a few superstitions about ash trees to play up the old-world idea of horror. It’s also deeply unnerving to watch people die horribly from a combination of apathy and occult revenge, with the most striking portion being the lead-up to the death of Sir Richard (Sir Matthew’s grandson), who eschews all the warnings even as you know his death—again foretold by a random passage in the Bible—is probably inevitable. At least in his depiction, James makes the undeniably horrible moments of the climax a little softer, as Sir Richard is a jerk who doesn’t listen to anyone (per James, he is a “pestilent innovator”) and insists on sleeping in a cursed room while ignoring all signs of danger.

What James proves with “The Ash Tree” is that subversion is an art. It requires understanding of the genre and its associated devices, but it also needs to be effective on all fronts. If it’s too humorous, you sacrifice the horror and tone you’re trying to interrogate. Too horrifying, and you’ve just written another horror story along similar themes of whatever you’re using the story to critique. Without a deep enough understanding of the genre and sub-genre you wish to discuss, then you’re just reversing the common plot elements without spending the time and effort to make something that interrogates and discusses the aspects you’re attempting to critique. In all these things, “The Ash Tree” succeeds with flying colors. The images are terrifying, the subversive elements shine throughout, and the grim sense of humor underscores both of these strengths perfectly. It drags the traditional Gothic into a much more modern space, critiquing the creakier aspects of Gothic literature, the motives behind the English witch trials, and in some cases the people behind those structures. Finally, it does all of this while still being an utterly terrifying story of supernatural revenge.

And now to throw it over to you. Do you think M.R. James was a serious influence on modern horror? What’s your favorite James story? Was Sir Matthew Fell an early representation of the HOA? Please let us know in the comments.

Sam Reader is a literary critic and book reviewer currently haunting the northeast United States. Apart from here at Tor.com, their writing can be found archived at The Barnes and Noble Science Fiction and Fantasy Book Blog and Tor Nightfire, and live at Ginger Nuts of Horror, GamerJournalist, and their personal site, strangelibrary.com. In their spare time, they drink way too much coffee, hoard secondhand books, and try not to upset people too much.

What is HoA?

My favorite M.R. James story is definitely “Oh, Whistle, and I’ll Come to You, My Lad.”

@1: Homeowner’s Association.

King, Campbell and Lovecraft all credit him as an influence, so you can’t really deny his influence (other admirers include Ruth Rendell and Kingsley Amis).

The way the antagonists of the story are punished for small mindedness, bureaucratic corruption and adherence to dogma does feel very modern in concept. You could easily update the tale to a local politician swatting a neighbor who lets their grass grow tall.

Difficult to pick a favourite James story, but I’ve always loved The Ash Tree. James’ great strength is that he so often keeps the horror subtle and hidden for most of the story: Mrs Mothersole’s curse isn’t ‘All your descendants will die in agony’ but the delightfully ambiguous and ominous ‘There will be guests at the Hall’.

For Brits of a certain age, a James ghost story is a part of their Christmas memories, as the BBC would regularly dramatise one (although their version of The Ash Tree was an abomination). This has been revived in recent years by Mark Gatss, another fan.

As Dhaskoi says above, I certainly learned from his methods, and I see his influence on a couple of tales Lovecraft wrote after reading his work in 1926. Fritz Leiber and T. E. D. Klein admired and emulated him in their own ways. Here’s one of the pieces I wrote about him:

Montague Rhodes James (1862 – 1936) is one of the absolute masters of the British tale of terror. He refined the tale of supernatural terror and, given his fondness for narrative play and overt references to generic tropes, can be cited as one of the field’s first modernists. His ghost stories are a British institution. I’ve seen them praised for their cosiness, their atmosphere of academia and Edwardian male camaraderie, and their reputation for providing a comfortable shiver or two. I would say all this underrates and misrepresents the author’s contribution to the genre. Far from being cosy, his stories frequently present a reassuringly ordinary setting that is invaded by the malevolent and terrible. Sometimes everyday objects take on or harbour hideous life, and at times the juxtaposition of these elements borders on surrealism. He was among the first to make the tale of supernatural terror as frightening as possible, an effect he achieves by an inspired and precise selection of language. Many of his most effective moments are inseparable from his style. No writer better demonstrates how, at its best, the ghost story or supernatural horror story (either term fits his work) achieves its effects through the eloquence and skill of its prose style – and, I think, no writer in the field has shown greater willingness to convey dread. He can convey more spectral terror in a single glancing phrase than most authors manage in a paragraph or a book. He is still the undisputed master of the phrase or sentence that shows just enough to suggest far worse. Often these moments are embedded within paragraphs, the better to take the reader unawares; the structure of the prose and its appearance on the page contribute to the power of his work.

His influence alone would ensure him a place in the pantheon. As with all influential writers his superficial traces can be found in the work of some bad ones – M. P. Dare was surely his most ludicrous literary offspring, and hardly one he would have been pleased to acknowledge – but such excellent and different contributors to the genre as L. P. Hartley, Fritz Leiber, Kingsley Amis, T. E. D. Klein, Terry Lamsley and Adam Nevill learned from him. He even appears as a character (Dr Matthews) and tells a new story in Penelope Fitzgerald’s superb novel The Gate of Angels.

No writer of fiction aimed mainly at adults gave me more childhood nightmares and night fears. It quickly became apparent to the shrinking short-trousered Campbell that James habitually described just enough to suggest far worse, and I would be much less of a writer without him. In a tale called “The Guide” I attempted to acknowledge my debt in full, but much else of mine would be poorer without his example. I think the figure that chases our hero uncannily fast across the soft sand in Thirteen Days by Sunset Beach could have scurried out of his imagination, and the scuttling subterranean denizen of the abandoned Greek monastery in that novel owes something to him too. The shape that sits up in a coffin, only to leave some of itself behind, in The Influence surely shows a trace of James, and so does the face that dangles from a ceiling in The Wise Friend.

Among James’s many memorable horrors are the sheeted spectre of “Oh, Whistle, and I’ll Come to You, My Lad” that shows “a face of crumpled linen”, the thing that crawls out of the well in “The Treasure of Abbot Thomas”, the various dismaying manifestations of the powers of Count Magnus and his tentacled friend (surely an influence on Lovecraft), and the unwelcome visitor on all fours mistaken for a dog in “The Diary of Mr. Poynter”. “A Warning to the Curious” offers perhaps the most sustained sense of relentless menace. You can find all these and many more dreadful delights in any collected edition of his ghost stories, a term that really doesn’t do justice to the sense of the monstrously inhuman or no longer human in his tales. His spectres inhabited the dark of my youth, and they’re waiting to creep into yours. Good ghosts never die.

Nicola Upson’s Nine Lessons is another homage by an amazing author who inhabits the territory between detective fiction and horror.

This is one of the most effective M.R. James stories, I think maybe because it’s more fully developed? I was re-reading him a few weeks ago. Time really does give you a fresh perspective on an author. Nobody could doubt James’ ability to conjure up a sense of dread or a sense of place (or fault his inimitable style) but a lot of the early stories struck me as being all set-up – ie, they were over almost before they began.

I like oh whistle and I’ll come to you my lad, and a warning to the curious with an honorable mention for the mezzotint

Personal faves would include “Casting the Runes”, “Count Magnus”, and “The Stalls of Barchester Cathedral”.