This is certainly one of the more difficult reviews I’ve had to write. My first draft was just “DUDE. AWESOME.” repeated a thousand times, but apparently that doesn’t cut it as a functional review. I’ve read this book a few times now and besides the one you’re about to read, the only other summary I could come up with was full of expletives and GIFs. So let me explain to you why The Coldest War is utterly “DUDE. AWESOME.”

Bitter Seeds set up Tregillis’ vision of an alternate WWII, one where sinister German scientist Dr. von Westarp built a mini-army of magic-enhanced super soldiers: psychic twins, firestarter Reinhardt, flying man Rudolph, invisible woman Heike, brute dullard Kammler, incorporeal Klaus, and mad seer Gretel. The Nazis funded his work and, in return, von Westarp sent his creations out to crush Europe and Britain with Hitler’s might. The only thing stopping the Germans was a cadre of British soldiers, a handful of stubborn wizards, and the terrifyingly powerful Eidolons.

The Coldest War picks up twenty-two years after the end of Bitter Seeds. We’re smack dab in the middle of the Cold War, except the U.S. isn’t involved the war ended before Pearl Harbor, meaning the U.S. never fought, meaning we never got out of the Great Depression, meaning everything pretty much sucks stateside. The whole of Europe, from the Channel to Asia and the Middle East, is isolated by the Soviet Iron Curtain, and lonely, isolated Great Britain fears the U.S.S.R. as much as the United States did in real life. Just replace potential nuclear holocaust with mystical annihilation and you get the idea. The Soviets have had two decades to refine von Westarp’s developments, and the supermen they created put the Reichsbehorde to a damn, dirty shame. When the timing is right, siblings Gretel and Klaus escape their Commie captors and flee to England.

Meanwhile in the U.K., Will has recovered from his death wish and drug-induced delirium and has a lovely wife, productive employment, and non-wizardly home life. Guilt, however, wracks him, the ghosts of all those innocents killed for Eidolon blood prices haunting his happiness. Wizards involved in the WWII efforts have turned up dead of mysteriously mundane causes, and Will might be next. Marsh and Liv’s marriage has curdled under the strain of raising their insane, incapacitated son. She’s turned to other men and he’s drowning at the bottom of a bottle. When Gretel and Klaus waltz into Milkweed HQ, neither hell nor high water can keep Marsh from rejoining the force and exacting his revenge.

Marsh, Will, Klaus, Gretel, no one in The Coldest War is what they appear (with the exception of Reinhardt he’s a bastard through and through). Marsh is an asshole who hates who he is, hates that he can’t be the good man he used to be, and hates the world for pushing him into a corner and trapping him there. Will is a good man playing at being an avenging angel and failing miserably. Klaus was built to be a destructive soldier but really just wants to live in a nice little flat somewhere and paint. Gretel is, well, Gretel: complex, paradoxical, and completely unhinged. She’s always playing several games of chess simultaneously and all on the same board.

And that’s one of the most enjoyable things about this book. Yes, the scenes where the technologically superior Russian super soldier fights older model Klaus and where the creepy Children of the Corn kids summon the Eidolons are sufficiently made of win. But the characters are always the key for me. In Bitter Seeds I felt the deepest affinity for Will; he always seemed like he needed a hug. Seeing him twenty years later matured, and yet still the same impulsive child he always was, was sweetly sad. This time around I thought I was going to feel sympathy for Marsh, but instead it was Klaus who tugged on my heartstrings. We got a glimpse into his mind in the first book, but with the sequel we see him as a middle-aged man who has had the luxury and punishment of time to ponder and resent his youth.

Not only is reading about these people pleasurable, but the physical act of reading is a joy in and of itself. Tregillis has this way with words, like a structured poetry, iambic pentameter imposed on prose. He doesn’t waste words or overuse flourishes, yet there’s nothing terse or laconic about his writing:

Something entered the room. It oozed in through the fissures between one instant and the next. That dreadfully familiar pressure, that suffocating sense of a vast intelligence suffused their surroundings. Even the air felt thicker, heavier. More real. The floor rippled underfoot, as the geometry of the world flowed like soft candle wax around the searing reality of the Eidolon.

His work is like falling down a rabbit hole: once you start it’s impossible to put down. I got so emotionally wrapped up in the story that by the end of the big action scene in Will’s mansion I was shaking. Still not convinced? Try this.

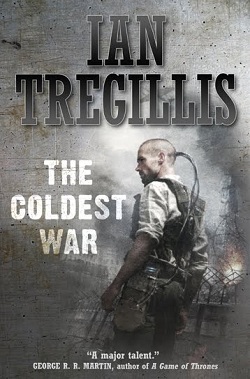

With Bitter Seeds, I checked it out of the library on a whim I was suckered in by the cover and by the due date I’d read it cover to cover twice, then went out and bought it and read it again. Next to Histoire d’O, A Short History of Nearly Everything, Deadwood, and Stardust, Bitter Seeds is probably the most dog-eared book in my library. In fact, there are only three books I’ve ever taken notes in (as in words to look up and delicious turns of phrases) on the back pages: American Gods, Pride and Prejudice, and Bitter Seeds. When I found out Ian was giving a reading at WorldCon last year, I drove to every bookstore in the Reno metropolitan area looking for a copy of Bitter Seeds after failing to bring mine with me and ended up begging his last copy off him. Two years I’ve waited for The Coldest War. Two long, long, long years. So yeah, I was a little excited. Just a skosh.

Yet, when I got an ARC of The Coldest War at the end of May, I didn’t even open it until June 24. I finished it the next day. Why wait so long for a book I knew I’d love written by an author I’m exceedingly impressed with? Because I dreaded finishing it. I didn’t want to finish it. I wanted to read it forever and ever. The only reason it took me 36 hours to get through it was because I kept stopping every few hours to watch Pushing Daisies, both to de-stress from the intensity of the book and to delay the inevitable completion as long as possible. And when I did, when I read Gretel’s famous last words, I closed the book and said “Holy fuck.” It took me a good 10 minutes to calm down enough to get off the patio chair and head inside where I laid down on the bed and started it all over again.

I’m sure I’ve said this before, but the way I feel about books mirrors my attitude towards people. I’m indifferent to 70% of them, actively loathe 15%, tolerate/like 10%, and genuinely adore the remainder. The beloved few are the ones that I constantly buy copies of so I can lend them out to everyone I know. I read them endlessly, talk about them nonstop, and worship at the author’s temple. Of course, it helps when the writer turns out to be a pretty cool dude. Who wouldn’t love a nerd who ruins cooking classes and is afraid of moths? I mean, come on, he looks like scrawny Steve Rogers for crying out loud. Adorbs.

Alex Brown is an archivist, writer, geeknerdloserweirdo, and all-around pop culture obsessive who watches entirely too much TV. You can keep up with her every move on Twitter and Tumblr.