Like most children of the ’90s, I loved nothing more than running around and hitting things with sticks. I also loved pretending that my bike was a horse, and I spent many hours charging up and down my grandparents’ driveway jousting, aka knocking a bucket off a wall with a bamboo cane.

I was what was widely misinterpreted as a tomboy.

Except I wasn’t.

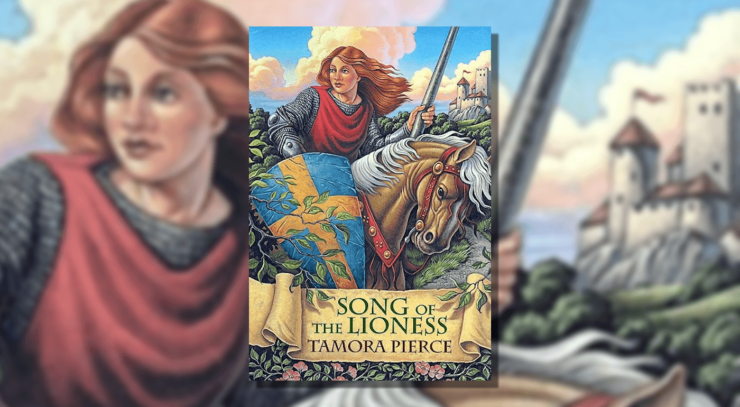

I was genderqueer but I didn’t have the words to explain myself yet (and wouldn’t for almost twenty more years), but I did have a role-model: Alanna of Trebond, Tamora Pierce’s first Lady Knight. The Song of the Lioness Quartet follows Alanna from an aspiring page to a fully qualified knight, as well as her journey from a girl pretending to be a boy called Alan, to being confidently and exactly Alanna. Books one and two of the series were always the most interesting to me, as Alanna struggled to reconcile her gender and identity with her aspirations of knighthood.

The importance of representation, especially in children’s media, cannot be overstated, and the first time you see yourself reflected on the page in someone else’s words is a moment that sticks with you for the rest of your life.

For young Esme, that was Alanna.

In her, I saw reflected my stubbornness and determination, the righteous indignation that got me in trouble at school when it was clear the rules were wrong. In particular, Alanna’s book-long feud with Duke Rodger, the beloved sorcerer and king’s brother who is universally trusted and respected by all except Alanna whose instincts correctly scream danger. Despite everyone else telling her she’s wrong, Alanna remains distrustful and diligent, even when it causes conflict between herself and her friends. I remember being ten on vacation with my grandparents, and witnessing a father bullying his son to climb to the top of the climber in the playground. The kid was clearly terrified and the man would not let him get down until he got over the top. I remember my own furious tears, yelling at the man to leave him alone and being hustled away by my grandparents. I couldn’t understand why no one else could see the injustice. I was always fascinated by a female hero who was willing to stand up to and against the status quo in the name of what is right, and Alanna’s character really emphasized to young Esme that just because something is widely accepted, that doesn’t mean it’s right.

Triumph comes with difficult consequences for Alanna. Even when she achieves her shield, having been outed as a girl, she is treated with suspicion by the community, and Alanna chooses to leave them rather than stay to justify her identity. Though this is Alanna’s own choice and only temporary, leaving her friends and home behind instead of staying to celebrate her shield is tearful. This moment in particular speaks to the reality that many queer folks have to face—choosing between living a lie or living peacefully with those they expected to love them. The battle is far longer and more complicated than a duel with swords, especially when it’s our most loved ones who are doing us harm.

Alanna was fiercely unapologetic in who she was and, as a preteen when everyone around you is navigating new social rules and trying to fit in, that was revolutionary.

I didn’t come into my own queer identity properly until my late teens, and I didn’t realize I was genderqueer until my late twenties. But when I recalled the times I spent as a child devouring Alanna’s adventures and rereading them as an adult, everything clicked into place. Alanna wasn’t just a girl who didn’t want to be a girl. Alanna wasn’t a girl. My baby-queer heart was certain of it! Perhaps not in as many words—on the page, Alanna succeeds despite being a girl and accepts the label as part of herself. But even so, the disconnect between physical and internal gender was something I was becoming increasingly more aware of in my own body, most of all hating the way that outside perception could be skewed so easily in the wrong direction unless I wore what felt like a costume. When Alanna is finally revealed to be a girl at the end of book 2, it is both devastating and freeing; terrifying and a relief in the same breath. Though effectively outed against her will, Alanna has no reason to hide anymore. She is a knight and a woman, whether others accept her or not. She is both, equally and simultaneously, instead of being compelled to choose one or the other from moment to moment. Ultimately, she is complete as herself.

Tamora Pierce never uses the words trans or nonbinary on the page. She didn’t need to—and during the time they were published in the 80s, couldn’t—but they were there the whole time. Not just Alanna, but countless others. We were all represented in Tortall, even if only in subtext.

You see, queer folks grow up in the unspoken margins—expertly finding grains among gravel and making a meal of it. We often exist between the lines, in a throwaway remark that skirts the line between canon and headcanon. To me, and so many, it is obvious that Tamora Pierce’s cast is one of diverse queerness: Raoul is bisexual, shapeshifting Daine is trans, Kel is ace, and Neal is an absolute mess. One of my greatest joys is meeting other Tamora Pierce fans out in the wild and excitedly swapping stories of how being allowed to grow up in those books helped us to become our best selves—fierce, flawed, and entirely, unapologetically ourselves.

When it came to creating my own characters for Sir Callie and the Champions of Helston, I knew that my mission was similar but not the same. The new generation of young readers deserves and demands more than subtext, especially in a world where ill-meaning adults are doing everything in their power to deny them their identity. These adults read Alanna, the same words that gave such validation to so many, and minimize her identity to merely “girl.” Tamora Pierce and Alanna taught me that knights fight for right, for the weaker, and for themselves.

Buy the Book

Sir Callie and the Champions of Helston

In 2020, amid the new pandemic and the normalized hatred of our current era, it felt more important than ever to send a new character out to join the battle.

Sir Callie and the Champions of Helston and its sequel, Sir Callie and the Dragon’s Roost, are a love letter to Alanna, and an ode to every author and character who paved the way through the genre. Sir Callie was never an answer to a problem, nor written in critique of a lack of explicit representation, but one more part of an existing, timeless collection. Subtext no longer protects children; disguising one’s identity is no longer the smart move it was twenty years ago. Those who seek to silence and invalidate queer identities must know that we exist in droves, that we will fight for our children, and that we don’t deserve to be afraid.

Likewise, it was important to me that Callie understands at the end of the book that the work is only beginning, They may have solved the most pressing problem of a certain bigoted, lord chancellor and his reign of terror against all who do not adhere to strict gender roles, but that enemy is a product of a much larger issue, the same way the 2020 election felt like a hard-won victory but the deep-rooted issues were only just beginning.

There are many readers who will spend a few hours with Alanna and Callie and enjoy a children’s adventure where good wins out and all is well. That is a valid reading of both books—at the heart, fantasy is escapism, after all. But fiction, even children’s fiction, does not exist in a vacuum. Every sentence, every word, arms its readers with the tools and weapons needed to fight for the better world they deserve to live in. A world where our destinies are not defined by our assigned gender, nor limited by our identities. That world is, as of 2022, as fictional as Tortall itself, but fantasy is hope, and hope is worth fighting for.

And every kid deserves to know they are not fighting alone.

After cutting their teeth on a steady diet of fanfiction in the South-West of England, Esme Symes-Smith wandered north to Wales for their degree in Literature and Creative Writing then promptly migrated to Missouri after meeting their wife on Tumblr. Esme has been a ghostwriter, an editor, a frozen-yogurt seller, a caffeine dealer, and now wrangles preschoolers for a living. They have a severe tea problem.