This past weekend, I read Emily Tesh’s Some Desperate Glory. Not quite in one sitting—sleep was required, at one point—but in under 24 hours. I’d given myself permission to just read, to not do any of the things that were nagging at me, and I took that permission and ran with it.

The book is fantastic; you shouldn’t, by now, need me to tell you that. But a detail in the way it’s presented got me thinking about what a reader does or doesn’t want to know when they pick up a book. This is not so much a matter of what counts as a spoiler—an eternal debate in which I do not wish to embroil myself!—but what information is too little, what is too much, and what is just enough.

The description on the cover of Some Desperate Glory tells you something very key, very terrible, about what the story holds for its protagonist, Kyr. She is a teenage girl who’s been raised on a human separatist space station, every minute of her days regulated; she’s brainwashed and controlled and she doesn’t know any of this, because she believes. She wants to get assigned to a combat wing of the station, to make use of all the skills she’s been taught in the way she believes is most valuable. Instead, she gets assigned to Nursery, which is where women birth and raise the next generation.

This could, in a different world, be presented as a horrible reveal, a fate you don’t know is awaiting Kyr. But it’s right there on the back of the book, and that changes the way the book asks to be read. Nursery isn’t a shocking fate; it’s an inevitable one, in the sense that you know it’s coming, and therefore you dread it, constantly, until it happens. You’re meant to feel that dread, to think about where it comes from, and what this world is doing to its women, and how all of this has shaped Kyr into the hot mess of a person that she is. (I love her. But she’s also a pain in the ass tyrant with a lot to learn.)

Two days after I read Some Desperate Glory, I read Tajja Isen’s “The Case for Never Reading the Book Jacket” at The Walrus. “These days,” she writes, “I refuse to read the jacket copy in full unless I absolutely have to. Jacket copy offers neither an effective barometer for predicting what I love nor reliable protection from buying things I regret. It is reductive, misleading, and—I have decided—none of my business.”

The constant problem with jacket copy, if there is one, is that it can’t be for everyone—it can’t be for a reader who only wants to know the vibes; a reader who wants to know all the bad things and if there’s going to be a relatively happy ending; a salesperson trying to get a bookstore to stock the book; a casual reader wondering if this is their next favorite writer; a superfan who wants to know what to expect from a beloved author’s new book; and every other reader or potential reader under the sun. There are more specific problems—trends, clichés, overblown superlatives a publisher might put on every single new release—but the main one, the one there’s no getting away from, is that every reader wants something different.

What do you want to know, when you pick up a book? What makes you pick up that book in the first place? Something gets you before you even get to the words on the back, right? The cover, the author, the title, the section it’s in in the bookstore, the review you heard on NPR, the friend sending you frantic texts about how much they loved it? Would you pick up a book just because a friend loved it, even if it were a blank rectangle with no cover text, no title, no nothing—just the words inside? Do you want to know the microgenre it belongs to, the tropes it deploys, the character types, the kind of pairings?

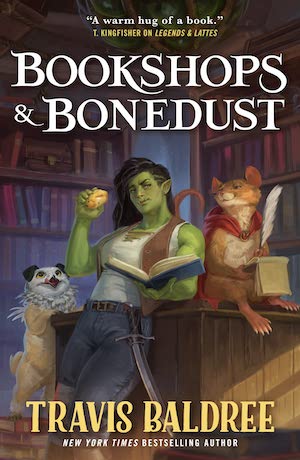

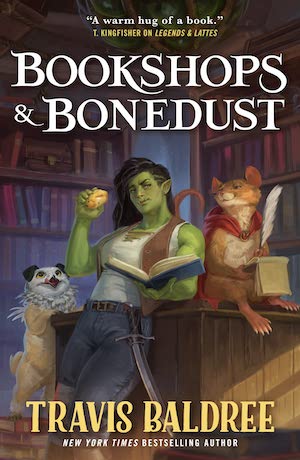

Buy the Book

Bookshops and Bonedust

There’s no right answer, obviously. Even Isen eventually comes around to the fact that jacket copy is, for the most part, necessary: “To do away with jacket copy would be to exclude the segment of the reading population that encounters books that way, readers for whom knowing what a book is about helps them decide whether to give or withhold their attention.”

And this is what I wonder about: What else helps us decide whether we want to spend hours with a specific book? What happens when that jacket copy says one thing and the experience of the book is something else entirely? Which books have gone unrecognized because the copy didn’t speak to the people it needed to speak to? How is it that sometimes, against the odds of all the books published in a given year, a book still finds its way to the hands of thousands of just the right readers?

I don’t even know if I can answer these questions for myself: What do I want to know before I read a book? I want to know what in that book is going to speak to me. I want to know if it has SFF elements; I want to know if there are fairy tales in its genes; I want to know if there are women with swords, if aging isn’t viewed as a curse, if the sentences are going to draw me in or kick me out again. I want to know when “dark academia” is actually going to mean “school is a very real part of this story” and I want to know when I’m going to fall in love with every single member of an ensemble cast. I want to know if the goddamn dog is going to die, so I can not read that book. I want to know what happens at first, but not what happens in the end. I want to know if there is something in a book I’m going to absolutely love and I want to hope that there is something in a book that is absolutely going to knock me over and make me stare into space for ten minutes.

Cover copy can only do so much.

So maybe, like Isen suggests, sometimes you just skip it. Or maybe your reading time is so limited that you read every single thing you can about a book before you even look at the first words; maybe you want to know exactly what you’re getting into. Spoil everything, and then watch how the pieces all line up. Maybe it’s different for every book. Do you think about this? Do you know what you want to know?

Molly Templeton lives and writes in Oregon, and spends as much time as possible in the woods. Sometimes she talks about books on Twitter.