There’s a scene in Sandman #56, the last of the six issues collected in the World’s End trade paperback, that provides a grim context for the Chaucerian tales presented within the book. We see—through the eyes of the characters looking out at the night sky from the tavern at the end of the world—a spectral funeral march, with Desire and Death of the Endless sorrowfully trailing behind.

The rest of the story arc is divorced from the ongoing saga of Dream and his impending doom. But with a title like “World’s End,” even the single issue short stories bode something far different than they did in previous anthology-style arcs. Titles like “Dream Country” or the collection called Fables and Reflections implied a kind of somnabulistic reverie, even if some of the stories were tinged with melancholy. “Worlds End,” though? That’s not a hopeful pairing of syllables.

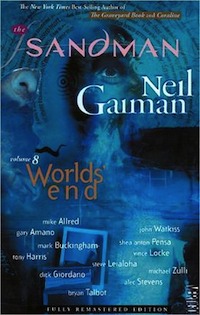

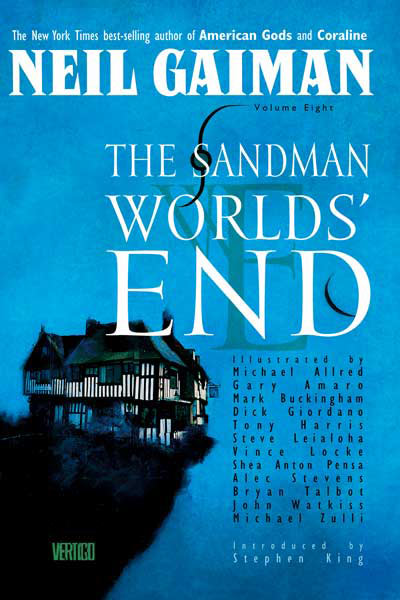

But, as I’ve mentioned many times in my reread of Neil Gaiman’s Sandman, the series is as much about stories and the art of storytelling as it is about the specific adventures of a pale king of dreams, and what World’s End gives us is a nest filled with tales of all types. In his introduction to the collected edition Stephen King says, “It’s a classic format, but in several of [the chapters] there are stories within the stories, like eggs within eggs, or, more properly, nested Chinese boxes.” King calls it “challenging stuff,” and he’s right. It’s similar to what Gaiman had done before in previous short arcs that collected one-off tales in the corner of his Sandman mythology, but Gaiman’s narrative ambition in World’s End pushes it to ever farther extremes. The stories—and the storytellers—comment upon themselves and their own traditions, while fitting into an elegant framework that ties the whole bundle of lives into the larger scope of the Endless adventure.

In short, of the three collected short-story volumes within Sandman proper, World’s End is not only the last of them, but it’s the best of them. Here Gaiman shows what he can do, maybe as a way to say goodbye to all the kinds of comic book stories he knew he wouldn’t be able to tell elsewhere. It’s important to remember that Sandman is not only Neil Gaiman’s first major work in comics, it’s his only major work in comics. Though he would do other small stories—with the Endless, with a time-tossed reimagining of Marvel’s core characters or his revision of Jack Kirby’s Eternals—he would never pour himself into his comic book work quite the way he did during his Sandman run. His novels and prose stories would become the outlet for that in his post-Sandman years. But while the series was running, Gaiman seemed to be overflowing with different kinds of stories he wanted to examine, and World’s End was the last chance for him to carve them into the stone tablet of the comic book medium.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. Sandman isn’t over yet—there are still two more books to go after this one—and plenty of ancillary volumes as well. So, let me quit my pontificating about Gaiman’s larger career and get back to the guts of World’s End to explore what mysteries it holds.

The six stories that comprise the World’s End arc share a single framing device. These are travelers from distant lands, caught up in strange storms, who have all found themselves at an inn called “World’s End.” And they all have stories to tell. It’s precisely the same device that was used in the 2008-2011 Vertigo series House of Mystery, created by Bill Willingham and Matt Sturges. That series lasted 44 issues, powered by a great pool of guest artists and a central Lost-like mystery where that characters tried to escape the strange confines of the house and figure out its purpose. In World’s End, the purpose of the house is obvious—it’s a narrative device to get all these odd characters together—and though individuals in the story may wonder why they’re here or where “here” is, they can all leave when the storm ends. After the funeral march in the sky. Though some decide to stay in this story-rich limbo, rather than return to the realities of their lives.

Like the other short-story-collection arcs, World’s End is also a chance for Gaiman to pair up with interesting artistic collaborators. And with different approaches comes some playful experimentation. The sturdy lines of Bryan Talbot (inked by Mark Buckingham) detail the framing sequences, inside the “World’s End” building itself. Talbot and Buckingham draw characters from strange realities—pirates, elves, centaurs, necropolitans, and salesmen—interacting comfortably, but without cartoony exaggeration. The characters feel real, and that matters in a story filled with as much unreality as World’s End.

The first of the nested stories tells about the dreams of cities, in a tale drawn by Alec Stevens. Stevens is rarely discussed these days, but in the 1990s he produced a significant body of idiosyncratic comic book work for Piranha and Paradox Press (among other places), and his unmistakable style is one of bold geometric shapes and captions floating in white space. His pages were closer to design-punk storybooks than traditional comic book pages, and in his collaboration with Gaiman here he captures the panic and paranoia of a man who fears the day when the great slumbering cities awaken. A strong start to a strong collection.

The first of the nested stories tells about the dreams of cities, in a tale drawn by Alec Stevens. Stevens is rarely discussed these days, but in the 1990s he produced a significant body of idiosyncratic comic book work for Piranha and Paradox Press (among other places), and his unmistakable style is one of bold geometric shapes and captions floating in white space. His pages were closer to design-punk storybooks than traditional comic book pages, and in his collaboration with Gaiman here he captures the panic and paranoia of a man who fears the day when the great slumbering cities awaken. A strong start to a strong collection.

The second story brings in the always-underrated John Watkiss to draw an unreliable story from the faerie Cluracan. The storyteller himself later admits to throwing in a sword-fight and a “few other details and incidents” to “add verisimilitude, excitement, and local color to an otherwise bald and insipid narrative.” Such claims—and the clear doubt from the listeners about the truth of the tale—would render the story pointless in the hands of another writer. “It was all a lie” and “it was all a dream” are two of the greatest anticlimaxes ever. But in Sandman, all the stories are dreams, all “lies,” but that doesn’t make any of them less true.

Young Jim narrates the third tale in the collection, a classic seafaring adventure, with a leviathan and all. But it’s really about Jim, a girl trying to pass as a boy so as to have opportunity in the world. And Hob Gadling—Dream’s old friend—also plays a central role in Jim’s journey of self-awareness in this story. Michael Zulli draws this one, and his artwork plus the simple-but-transformational twist and exciting events of the chapter means that we have three excellent stories in a row to kick off the World’s End collection.

“The Golden Boy,” in the fourth issue of the arc, is the best of them all.

Drawn by Mike Allred, this is Gaiman’s retelling of the story of Prez Rickard, the protagonist of the 1970’s DC series Prez, created by Joe Simon and Jerry Grandenetti. The short-lived series told about the first teenage president of the United States of America. In Gaiman and Allred’s version, Prez’s story continues well beyond his idyllic early adventures. It’s a kind of dark Forrest Gump version of America, if Forrest Gump were any good and if it explored the quixotic weirdness of an America in decline and guided by divine creatures like the terrifyingly joyous Boss Smiley. Morpheus takes the no-longer-young Prez under his protection and gives him access to a portal, where “Some say he still walks between the worlds, traveling from America to America, help to the helpless, a shelter for the weak.”

In that one short tale, Gaiman and Allred pay tribute to the highs and lows of this country while celebrating a strangely wonderful Joe Simon creation and the Bronze Age comics scene that helped spawn it. It’s funny and haunting and tragic and hopeful in all the right ways.

Gaiman follows up that superior chapter with one that’s narratively complex but ultimately uninspiring. I had remembered the tale of Petrefax of the Necropolis (as drawn by Shea Anton Pensa and Vince Locke) to be one of the meatier stories in World’s End. And it might be, but with this reading I found its top-hat, skeletal characters to be defiantly uninteresting. The land of the dead seemed like a place not worth visiting, even in story, no matter how hard Gaiman tried to embed humor and irony into the pages.

I think my problem with the fifth story during this reread is that it tonally clashes with what has come before, even while allowing for the range of tonalities in the previous tales. With its hideously ugly art, ossified architecture, and dessicated characters, “Cerements” looks better suited for one of the non-Gaiman psuedo-Sandman stories that followed Gaiman’s Vertigo departure. It doesn’t have the majesty of even the most base of the true Sandman stories. At its best, “Cerements” is an E.C. Comics tale in Victorian drag. At it’s worst, it’s a grotesque bore.

Still, it’s only a fraction of World’s End, and with the sixth chapter devoted to the population of the inn, their observance of the chilling skyward funeral procession for Dream himself—even though that event won’t “really” happen for almost 20 more issues—calmer weather, and departure for those who choose it, the collection comes to a powerful close.

Even the unpleasantness of Petrefax cannot taint the overall quality of World’s End, the book in which Neil Gaiman didn’t merely dabble in the land story, but, instead, tamed its wild reaches and offered it up to the reader as a momentary tribute before the Dream would come to an end.

NEXT: The Kindly Ones bring retribution to the dream king and death looms.

Tim Callahan likes E.C. Comics about 37% more than he likes anything written by Geoffrey Chaucer, contrary to what may be implied above.