For 70 issues in the mid-1990s a sort-of-Sandman spin-off detailed the pulpy adventures of one Wesley Dodds, aka the Golden Age Sandman, in a series by Matt Wagner and Steven Seagle and (mostly) Guy Davis called Sandman Mystery Theatre. That series recast the original Gardner-Fox-and-Bert-Christman-created DC Comics Sandman as a plump amateur detective who would hone his skills on the city streets while trying to maintain his relationship with the lovely and whip-smart Dian Belmont.

I have my collection of the series bound in two customized hardcover volumes, if you’d like an indication about how much I enjoy Sandman Mystery Theatre.

But the series did have very little connection to the Neil Gaiman Sandman series from which it ostensibly sprung. At best, Sandman Mystery Theatre was brought to print because its title—and Vertigo label—might possibly get a few extra fans to notice, since it seemed like it might relate to Gaiman’s popular series. It’s not like Gaiman set up anything special with the Wesley Dodds character and then handed him over for a new creative team to expand upon. The only connection between Sandman and Sandman Mystery Theatre was the first word in each title, and one small reference in an early issue of Sandman where the narration briefly explains that Morpheus’s imprisonment led to the strange haunting dreams of Wesley Dodds.

Wagner and Seagle and Davis’s character-driven proto-superhero detective series was distinctly different than what Gaiman was interested in doing in Sandman. And the two protagonists from each respective series never teamed up and bashed ne’er-do-wells upside the noggins.

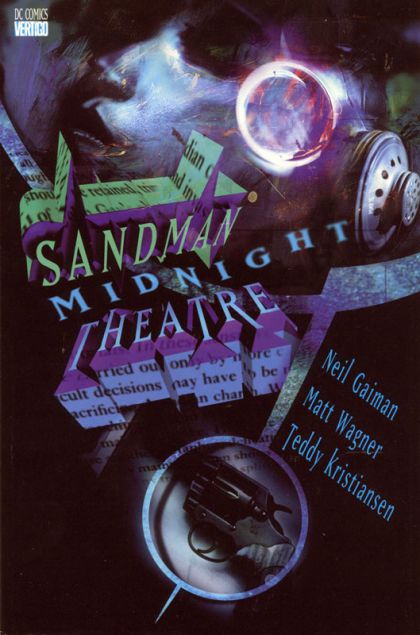

Except once. In the Neil Gaiman-written one-shot Sandman Midnight Theatre, drawn by Teddy Kristiansen, and released as Sandman proper was coming to an end.

And they didn’t really team up to smack around some bad guys.

But the stories of Morpheus and Wesley Dodds did explicitly cross over, for that one, dank and mysterious and memorable moment.

Sandman Midnight Theatre takes place firmly in the continuity of Sandman Mystery Theatre and Sandman (between issues #36 and #37 of the former and between panels of issue #1 of the latter, if you really must know), and though it was co-plotted by Wagner and Gaiman, the single issue was scripted by Gaiman and it reads like a noble effort to tell the kind of story that would fit into either series. That’s no minor feat, and yet it’s quite a successful one in the end.

To be fair, it’s more of a Wesley Dodds story than a Morpheus one, but since the king of dreams was imprisoned the entire time Dodds was operating as a gas-masked vigilante (circa the buildup to World War II), it’s impossible to provide them equal page space. But plenty Sandman stories didn’t revolve around Dream as a character anyway, so it all works out just fine as a not-quite-team-up.

Since it is a mostly-Wesley-Dodds story, it revolves around a mystery, with a blackmail case that has led to the suicide of some notable acquaintances. Hence, Dodds to England, and hence a series of events leading to a party in honor of one Mr. Roderick Burgess.

Burgess, you’ll remember, is the Crowlian figure who imprisoned Dream for most of the 20th century.

The party takes place at Burgess’s estate, with Morpheus imprisoned in the basement. There’s even a moment where Dodds ends up confronting his trapped namesake, in pursuit of the blackmailer he traveled to England to find.

There’s far more to the story than that, even if its narrative is completely traditional and linear in structure. It’s a crime story, with the fringes of mystical cultishness on its edges, and a weird dream lord in a bubble. But it’s still a crime story, and Gaiman tells it in grand style. His best, and wittiest, contribution to the tale is the character of the “Cannon.”

The Cannon is a kind of Robin Hood cat burglar who leaves his calling card—a picture of a Cannon—wherever he appears. He seems to be Gaiman’s tribute to the British rogue known as the Saint, famously played by Roger Moore and unfortunately played by Val Kilmer in their respective versions of the classic British thriller novels by Leslie Charteris. The Cannon, British archetypal pulp antihero, meets up with the Sandman, archetypal American mystery man. It’s quite a good blending of the two overlapping genres, and poor Dian Belmont is trapped between them, not because she’s a victim who needs saving, but because she’s absolutely fed up with the men in her life leading these strange secret lives, even if she has a few secrets of her own.

Gaiman has fun with the whole thing, in other words, and gives us a nice, juicy, pulp tale about blackmail, a satanic cult, high society, a pair of intrepid investigators/criminals, and an immensely powerful dream king wrapped in mystical bonds.

With the painted artwork by Kristiansen, though, Sandman Midnight Theatre doesn’t feel like a movie serial on the page. Instead, it’s like a series of woodblock prints, thickly colored, and projected into a gallery. I mean that as a compliment. Kristiansen’s jagged, painterly approach radically defies the relatively cliche march of the plot, and turns the story into a series of strangely alluring images. He brings, if I may say so, a dreamlike quality to the visuals that saves the story from its more straightforward instincts.

But perhaps I shouldn’t say that, because even if it had been drawn in a pedestrian manner, the story would still have Gaiman’s flavorful dialogue to give it plenty of charm. Kristiansen’s chiseled strangeness, almost in the manner of Marc Hempel but more impressionistic, catapults the book from a mere Sandman curiosity to an essential piece of the Gaiman comic book oeuvre. They make a good match, Gaiman and Kristiansen, and Wagner’s plotting contributions surely helped to make it the tightly-plotted little book it became.

Wagner even picked up the Cannon character and built a storyline around him in later issues of Sandman Mystery Theatre. And Wesley Dodds’ newfound understanding—Morpheus, though trapped, explains to the noble Mr. Dodds that a small piece of the dream lord resides within him, and gives him the strange nightmares that have helped him in his crimefighting career—can only give him more confidence as he goes forward from here. Even if it all seems like a dimly-remembered dream.

NEXT: Gaiman illustrated. Sandman: The Dream Hunters.

Tim Callahan would read an ongoing series featuring the Cannon, particularly if DC could somehow pull Teddy Kristiansen back into the fold to write and draw every single issue.