Ghost in the Shell (1995) Directed by Mamoru Oshii. Written by Kazunori Itō, based on the manga by Masamune Shirow. Starring Atsuko Tanaka, Akio Ōtsuka, and Iemasa Kayumi (with Mimi Woods, Richard Epcar, and Tom Wyner as the English dub voice cast).

In 1949, British philosopher Gilbert Ryle published a book called The Concept of Mind. In it he argues against René Descartes’ theory of mind-body dualism, the idea that the mind and the body are entirely separate, as the body is a physical thing and the mind is a non-physical phenomenon. Ryle coined the term “ghost in the machine” to critique this concept, but more broadly to critique how readily philosophers accepted Cartesian dualism without questioning the assumptions behind it or asking if they even understood the nature of the two things they had divided.

Among the people who read Ryle’s work was author Arthur Koestler, who in 1967 published a book called The Ghost in the Machine. Koestler was also critical of Cartesian dualism; he preferred a materialistic theory of mind, one in which consciousness is a result of the matter that makes up the mind, not from some non-material phenomenon separate from it.

Got all that? There will be a quiz.

I promise there is a point to this philosophy lesson. This is one of those cases where we know exactly what big ideas a sci fi story is drawing upon, because the author of the story has stated it plainly. Koestler’s book was one of the things that inspired mangaka Masamune Shirow when he wrote Ghost in the Shell. It was also, obviously, the source of the title, although when the manga was first serialized in Kodansha’s seinen magazine in 1989, the publisher wanted a more exciting, less esoteric title. So the manga was called Kōkaku Kidōtai (攻殻機動隊, literal translation: “Mobile Armored Riot Police”), with Ghost in the Shell as the subtitle.

It should go without saying that we are all glad the 1995 film uses Shirow’s preferred title, which is objectively much cooler—and, more important, much more fitting for the kind of movie it is.

Philosophers have been arguing about the theory of mind for a long time, and they’ll keep arguing about it well into the future, because that’s what philosophers do. And science fiction writers have always been around to turn those arguments into stories, because that’s what science fiction writers do. The nature of sci fi—specifically how it imagines to be real what is not real, but could be—makes it a powerful way to tackle questions such as “What is a mind?” and “What is consciousness?” and “What is life?”

Even better, sci fi lets us do it all within the context of cyborgs engaging in a violent shootout with giant crab-shaped armored tanks in an abandoned building, which is, of course, the best way to have any serious philosophical discussion.

Let’s talk about cyborgs.

The term “cyborg” was coined by research scientists Manfred E. Clynes and Nathan S. Kline in 1960 in an article in Astronautics magazine. In the article “Cyborgs and space,” the authors suggest that it makes more sense to technologically enhance the human body to survive space travel than it does to try to create livable human environments in space. They outline several biological problems presented by space travel that could potentially be solved by mechanical means: detecting and countering the effects of radiation, reducing the body’s metabolic requirements, taking care of oxygen and carbon dioxide exchange, and more.

My personal favorite is their suggestion that people on long spaceflights shouldn’t have to sleep, and cybernetic alterations to the body might make this possible. This is one of the most disturbing proposals regarding space travel that I’ve ever read. I love it (for its space horror potential).

Clynes and Kline write that space travel is an opportunity that “invites man to take an active part in his own biological evolution.” They acknowledge they aren’t talking about true hereditary evolution just yet, but about the more general notion of humankind deciding how it wants to evolve in the future and taking concrete steps toward achieving that.

Of course, the idea of cyborgs existed before Clynes and Kline coined the word. People have been imagining humans with machine parts for as long as there have been machines, and what they imagine has constantly shifted to match the world’s changing technology. Sci fi in particular has always played with the question of where to draw the line between a constructed object and a living, conscious being. (One could even argue that this theme is foundational to the genre science fiction, if one agrees that Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is a good candidate for the first sci fi novel.)

I’m not normally interested in splitting hairs with sci fi terminology, but you’ll have to indulge me just this once. The way people use the word “cyborg” in pop culture (especially in film criticism) is inconsistent, but the way I’m using it here is specifically in the way that Clynes and Kline defined it, which is also the way that Ghost in the Shell uses it: a cyborg is a human person whose biological body has been supplemented, enhanced, or replaced by technological additions. Some famous examples from across sci fi: Molly Millions in William Gibson’s Neuromancer (1984), the Borg in Star Trek: The Next Generation, RoboCop (1987), The Six Million Dollar Man (1973), and, of course, our old buddy Darth Vader.

The combination of human and machine is key, because cyborg stories are very often about existing in that murky, uncertain borderland of being neither wholly one thing or another. It’s a territory that allows a story to explore countless questions: How much of a person can be replaced and still remain human? When does the human become a machine? When does the machine become a human? Is there any point in drawing a line? What if the body changes but not the mind? What if the mind changes but not the body? (And what about a character like Jonas from Gene Wolfe’s Book of the New Sun, a machine whose body has mostly been replaced by organic parts?)

I could go on and on, but my point is this: Ghost in the Shell (the movie) builds on this science fictional foundation of cyborg stories to explore the philosophical concept of the “ghost in the machine.” It doesn’t bother to explain much; it assumes the audience is genre savvy enough to skip all the clarifications and definitions and jump right into the discussion about what it all means.

This streamlining was key to adapting the manga. Shirow’s manga is a relatively light-hearted police procedural of sorts, where episodic cases exist mainly to showcase the dense and detailed information about the technological, biological, and political implications of its cyberpunk world and the ideas Shirow wanted to explore, and also to showcase hot naked cyborg ladies getting it on.

The movie, by necessity, has a somewhat different approach. A film cannot explain itself in extensive footnotes, no matter how cool or interesting those footnotes might be.

In the early ’90s, director Mamoru Oshii was meeting with a producer from the film company Bandai Visual in hopes of pitching a project with them. Oshii was an established director of both anime and live action films; his recent work had included two animated films for the Patlabor franchise, which is about cops and robots in near-future Tokyo. The Bandai producer countered Oshii’s pitch with a pitch of his own: he wanted Oshii to adapt Ghost in the Shell. (The way Oshii tells this story is pretty funny.)

Oshii is a self-proclaimed lover of the most arty of arthouse cinema; he has frequently named filmmakers like Federico Fellini, Ingmar Bergman, and Jean-Luc Godard among his influences. He has also professed admiration for films from the more philosophical corners of sci fi, such as Chris Marker’s La Jetée and the works of Andrei Tarkovsky.

So he was clearly the right guy to adapt Shirow’s Ghost in the Shell into a lean 83-minute philosophical discussion about the nature of life and consciousness that is sometimes interrupted by gunfights. And hot naked cyborg ladies.

And it’s great. The 1995 film is great. I say this with complete sincerity: I love an 83-minute philosophical discussion about life and consciousness that gets interrupted by gunfights and naked ladies.

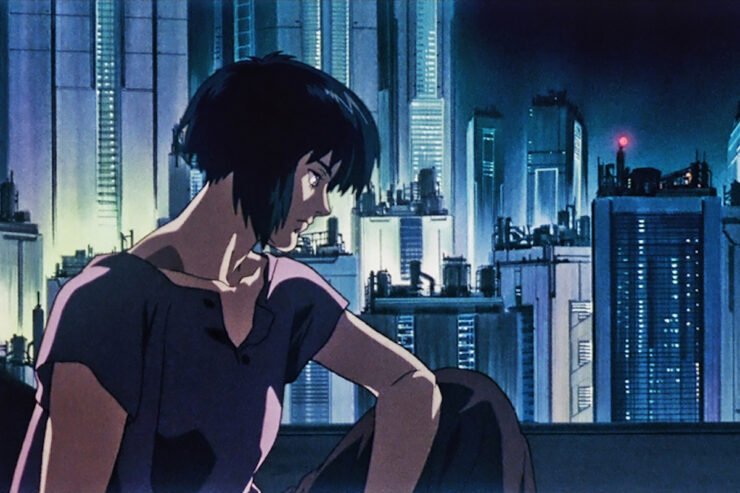

We are deep in neo-noir cyberpunk territory here, so the setting is especially important. I am completely comfortable speaking in superlatives, here: Ghost in the Shell has some of the most stunning urban art ever animated for film. New Port City is based on Hong Kong, with modern skyscrapers standing alongside the Old Town’s crowded waterways and marketplaces; the signs are in Chinese and several times we see airplanes coming in to land right in the center of the city, as they did at Hong Kong’s Kai Tak Airport. (You will waste a significant amount of time if you go down the rabbit hole of YouTube videos of landings at Kai Tak Airport.) The city is rich and complex, with visual cues that indicate several layers of urban expansion and deconstruction.

The city we see on the screen didn’t begin in the artists’ sketchbooks. It began on the streets of both Hong Kong and Tokyo. To create the Old City parts of New Port City, location scout Haruhiko Higami visited the locations to take photographs of key architecture, including what remains of Tokyo’s once-extensive network of old canals and Hong Kong’s famous Kowloon Walled City before it was demolished. The photos he took were in black and white; it was the art director Hiromasa Ogura who decided on that lovely rain-soaked, neon-washed color palette, a process that involved taking his own reference photographs in different conditions. Production designer Takashi Watabe designed the city’s gleaming, futuristic skyscrapers. It’s the combination of these elements—the old that references real cities and the new that comes from the imagination—that creates the complex, layered, and vibrant New Port City.

Ghost in the Shell combines cel animation and CGI to create its many striking images, the kind that make you want to pause and study the background because there is so much to see. The animation was done by Production I.G, whom western film buffs might know as the anime studio responsible for the animated sequence in Quentin Tarantino’s Kill Bill: Vol. 1 (2003), but anime fans will know them as the studio behind the wonderful Haikyu!!

The result is stunning. The high-angle views of narrow alleys and canals, the gleaming skyline that’s always in the distance, the visual riot of signage and advertisements, the shifts from dense crowds to abandoned blocks, the contrast between street markets and advanced laboratories—this is a city that feels overwhelming, baffling, cinematic, and strange. There is a constant, inescapable juxtaposition between previously destroyed and newly built, always emphasized by the vertical geography of a city that keeps reinventing itself right on top of its own decaying underbelly.

The music is an important part of the film’s atmosphere. For the opening theme, called “Making of a Cyborg,” composer Kenji Kawai combines a traditional Japanese wedding song and classical Japanese instruments with choral harmonies from Bulgarian folk music. You can hear the latter inspiration in Le Mystère des Voix Bulgares, the 1975 album from the Bulgarian Women’s Choir. The result is an eerie and entrancing score. It’s one of the best examples I’ve ever seen of a film using its opening music to set a distinctive tone.

A lot of the imagery and atmosphere in Ghost in the Shell is similar to what we’ve seen in other cyberpunk films, such as Blade Runner (1982), Akira (1988), and The Matrix (1999). But there’s a good reason for that: Filmmakers love the aesthetics of neo-noir cyberpunk because they work. In Blade Runner the purpose is to portray a version of Los Angeles that is dying beneath the looming pyramids and beckoning advertisements; in Akira Neo-Tokyo is consciously a city that is trying to build over its destructive past; the grim neglect evident in The Matrix’s anonymous American city reflects how the world inside the matrix was created as a virtual prison.

Ghost in the Shell’s New Port City is a crowded, layered megacity, where the older parts are drowning in history and humanity—and often literally flooded—and the new parts of so high as to be out of reach. It’s an echo of what we see of the society in the city; the first few minutes of the movie quickly introduce government officials, garbagemen, cops, and criminals, all linked together.

The city is also an echo of what we come to learn about the people who live in it: existing on different levels, not just in class and geography, but physical and technological, with the innovative new always in danger of erasing the unwanted old.

Our main character is Major Motoko Kusanagi (Atsuko Tanaka), a member of a law enforcement organization called Public Security Section 9, which is focused on information security and counterterrorism. This is a world where just about everybody has some kind of high-tech enhancement or hardware in their brains or bodies; the members of Section 9 range from the mostly-machine Kusanagi to the almost entirely human Togusa (Koichi Yamadera). There is a lot of potential for confusion in such worldbuilding, so it is one of the movie’s strengths that it sets this all up quickly: there is a mysterious hacker called the Puppet Master who might be planning an assassination, and Section 9 is trying to stop him. The Puppet Master is a “ghost-hacker,” meaning they can hack into people’s “ghosts,” or their minds, via their cybernetic parts.

I love the efficient way the film conveys just what “ghost-hacking” means in this world where people’s brains are electronically enhanced and connected. We learn that the Foreign Minister’s interpreter has been hacked for nefarious political goals; the main character herself is carrying out nefarious political goals, as the first thing we see Kusanagi do is assassinate a would-be political defector. All of that is pretty standard territory for a cyberthriller plot.

When the members of Section 9 trace the Puppet Master’s actions, they find a random garbageman, a nobody, just some guy who thought he met a man in a pub to help him with marital problems. But he doesn’t have marital problems. He doesn’t have a wife and kid at all. He only thinks he does because of false memories given to him by the hacker, completely replacing his memories of his real life.

The idea of false implanted memories is one of those delightful sci fi ideas that just gets more troubling the more you think about it. It’s a fairly common trope in sci fi in general, and especially in the gritty sci fi movies of the ’90s—for example, Total Recall (1990), Dark City (1998), and Strange Days (1995). But Ghost in the Shell skates past the usual elements of paranoia, doubt, and distrust to launch right into a much broader existential dilemma.

In the conversation Kusanagi and her teammate Batou (Akio Ōtsuka) have one night on a boat after a diving expedition, Kusanagi wonders what it means when the part of a person that they think of as themselves can be understood as a lifetime’s collection of data, and that data can be erased or altered like any other data. Batou points out that while Kusanagi’s body is almost entirely mechanical, she still has a human brain; to him, and to the general populace of the world they live in, that’s what matters.

The Puppet Master throws a complicating wrench into the works when it reveals itself to be not a well-hidden human hacker, but instead a self-aware artificial intelligence called Project 2501, which was created by a governmental organization as a tool for espionage and covert operations. It wasn’t designed to become sentient; it describes the process as becoming aware of itself while existing in a vast amount of data. It requests political asylum, arguing that if it can recognize itself as a sentient being, it ought to be treated as one—doesn’t it fit most of the criteria for life? As it explains to Kusanagi, it thinks it lacks only two things that would truly make it alive: the ability to reproduce that isn’t creating an exact replica, and the ability to die.

We could argue all day about Project 2501’s definitions of consciousness and life—but that’s the point of Ghost in the Shell. The argument is what the movie cares about, not the answers, because the entire thing is a thought experiment wrapped up in a cyberpunk action film. It’s a movie that very much wants you to come away from watching it filled with questions: What is consciousness? Can we really define it? Is it merely data, or is it something else? What are the key components of an individual? Is it the mind, the body, or both? And what is life? Is it merely a being’s physical processes, or is it something else?

I admire Ghost in the Shell as a piece of art, because it is truly beautiful in its creation of its vibrant, detailed world. But I also like it for being the kind of science fiction that asks questions we don’t have perfect answers to. We didn’t have those answers in 1995, and we don’t have them now. Sure, we have functional answers that work for most people’s everyday lives, but the nature of consciousness and the definition of life are things that scientists and philosophers still actively research and debate. I, for one, think that’s fantastic. The universe is a vastly more interesting place when we never stop digging into how the weirdest parts of it work—and that includes our own minds.

What do you think of Ghost in the Shell? What are your favorite scenes in the beautiful animation? This is another anime movie that gained international popularity mostly through its availability in home video formats, so who here first saw it through showing of an anime club’s VHS? I know you’re out there.

Next week: We’ve just spent some time exploring the mysteries of individual consciousness, so let’s get cosmic (and long) again with Contact (1997). Watch it on Amazon, Apple, and Microsoft.