When a story opens on a beach, in the wake of a harrowing plane crash, I think of Lost. It’s wired into my brain, a holdover from a very different era. But Madeline Ashby’s Glass Houses, apart from the plane crash, is not that kind of story—the kind that goes on, and meanders, and eventually lands somewhere not entirely satisfying. No, this is something very different: pointed and sharp, a thriller full of absurd tech, carefully laid plans, and extremely understandable anger. It is a rich text of rage and experience.

On the beach, staggering from the crash, is a woman named Kristen Howard, whose boss calls her Kiki. Said boss, wealthy manchild Sumter Williams, has survived; so has his equally unbearable right-hand man, Mason. There are only two other women among the survivors, because this plane was on its way back from a tech event, and—as Ashby makes bracingly clear—there isn’t really much room for women in tech, even if they fit into its categories of acceptability. (“A woman could do the whole jeans and ironic T-shirts thing, but the jeans had to be skinny and the woman had to be even skinnier.”)

Kristen is the chief emotional manager for Sumter’s Canadian startup, Wuv. Ashby gives just enough detail about Wuv to make it plausible: Sumter built it from an absolutely terrible idea about emotional currency, and tracking and quantifying emotion, and if you’re making a face right now, I was right there with you. Kristen’s job is whatever Sumter wants it to be: endless emotional labor plus keynote speeches plus helping him sell investors on the company. The tech is both the most immediately speculative element of this near-future tale and, in a way, the least relevant; its existence provides a framework for Kristen’s story and her plans. Because, as Ashby hints from early on, Kristen has her own plans, and they do not involve emotional currency.

But on the beach, stranded and scared, everyone has other things to worry about. Before long, the survivors come across a large, looming, glass fortress of a house. Getting inside is impossible, until a door simply opens. The house is well-stocked and peculiar. Why can’t Kristen turn on the taps? Why doesn’t anything have a brand name? How far down does the elevator go? And why, when two members of their party go out to scout the island, does one come back bloody and terrified, claiming that the island ate the other?

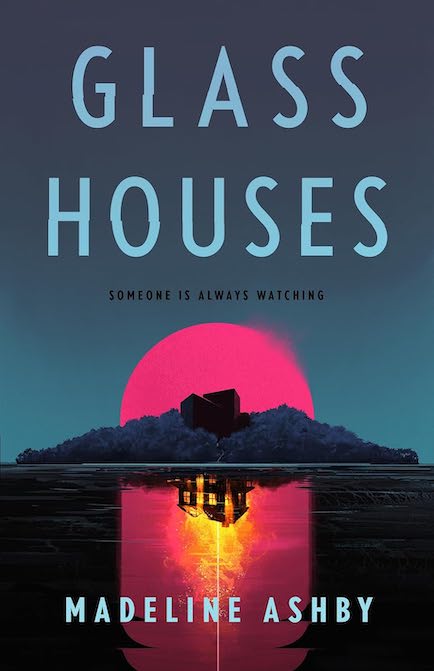

Buy the Book

Glass Houses

Ashby lays out her story in two timelines: One is the island survival tale, and the other dances through Kristen’s history, from her youth to the days just before the crash. Part of her story is about her unhappy childhood as the only child of parents who livestreamed her every move, letting the internet decide when she could leave the dinner table or what she could wear to school. When their house burned down, Kristen was left an orphan and badly injured; her scars are literal as well as emotional.

Another part is about her relationship with a man she meets at a weird Los Angeles party, who hides her from Sumter, helps her fix her makeup, and then falls into a fairly steamy affair with her. And yet another part—the part that spools out most slowly—is about what Kristen did before she came to work for Wuv.

Glass Houses isn’t so much a book of twists and turns as it is a slow burn of suspicion and satisfaction. Kristen has spent her life surviving among egotistical, oblivious men, and her anger burns low and constant; even her throwaway observations reflect how she’s been seen and treated, what’s been expected of her, and how she has played into or against those expectations. One of Ashby’s strengths is the way she relates what it feels like to be Kristen, physically, in the men’s world of her work. The feeling of someone’s unwanted hand; the way men react to her burn scars; Sumter’s too-closeness; the perfect way she describes a miserably hot day: “Stepping outside felt like being kissed by a boy who didn’t know how.”

But this book is also wickedly fun. Ashby has sharp words for everything from American tech bros to American speech patterns (to America, full stop) to terrible parents to terrible husbands to egregious misuses of tech, especially when it comes to surveillance and control. She is a crisp, wise observer of the norms of this world, and it feels at times like she has packed the accumulated wisdom—and exhaustion—of years into these pages.

Glass Houses is immersive, tart, fun, and full of dread all at once. When you can see the horrors coming and they are still deeply horrifying, that is a job well done. This is the case on both a scene level (Kristen’s keynote speech, interrupted most rudely, is a perfect example) and of the book as a whole: By the time things come to a head on the island, you can see what needs to happen, and you can almost see how it’s going to happen, and you still want to tear through the pages to learn exactly how badly things are going to go, how delusional a rich techbro might get, and how resourceful Kiki Howard can be when necessary.

If you like seeing awful people get their just deserts; if you like a locked room (or small island) mystery; if you like misguided-tech tales like of Severance or Made for Love; if you maybe would just like a book to reassure you that the misogynist nonsense you’ve put up with in your work life is real, and all too common, and that other people see it too—you’ll want to pick this one up. You may also find it hard to put down.

Glass Houses is published by Tor Books.