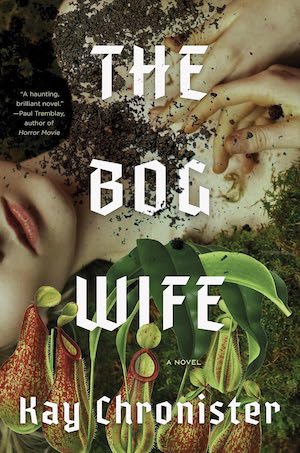

We’re thrilled to share an excerpt from The Bog Wife, a Gothic Appalachian horror novel by Kay Chronister, available now from Counterpoint.

Since time immemorial, the Haddesley family has tended the cranberry bog. In exchange, the bog sustains them. The staunch seasons of their lives are governed by a strict covenant that is renewed each generation with the ritual sacrifice of their patriarch, and in return, the bog produces a “bog-wife.” Brought to life from vegetation, this woman is meant to carry on the family line. But when the bog fails—or refuses—to honor the bargain, the Haddesleys, a group of discordant siblings still grieving the mother who mysteriously disappeared years earlier, face an unknown future.

Middle child Wenna, summoned back to the dilapidated family manor just as her marriage is collapsing, believes the Haddesleys must abandon their patrimony. Her siblings are not so easily persuaded. Eldest daughter Eda, de facto head of the household, seeks to salvage the compact by desecrating it. Younger son Percy retreats into the wilderness in a dangerous bid to summon his own bog-wife. And as youngest daughter Nora takes desperate measures to keep her warring siblings together, fledgling patriarch Charlie uncovers a disturbing secret that casts doubt over everything the family has ever believed about itself.

Before her return, Wenna thought many times about what it would be like to see her family again and a few times, with half-guilty yearning, of how it would feel to see the land where she had grown up, but she had not considered how it would feel for the land to see her, and now she thought that was what she should really have been worried about. The bog looked eyelessly; it felt knowing. The white pines and maples, leaning on their above-ground roots, seemed to incline their heads toward the car.

Her husband Michael would have said she was anthropomorphizing the plants. The first time he used that word, she asked him what it meant. He shrugged. It was a word he’d learned in school. Acting like things that aren’t human have human intentions, he said. Everyone learns that? Wenna asked. In school? She’d tried, after that, to see the vacancy in everything, but she felt now that Michael was wrong. The bog was not vacant. It had presence and intelligence, and, she realized, it had changed while she was gone in ways barely perceptible and too subtle to name. Were the trees farther apart? Were they taller? Had the moss on the trunks thinned some?

When the car rounded the driveway’s final corner and the house came into view, Wenna drew in a breath. The Haddesley manor was a massive old heap of stone that had been crumpling for longer than Wenna had been alive, but now almost the whole west wing was collapsed. The trunk of an enormous tree stuck through the roof and impinged on the front second-story windows. The east wing was intact, but just barely. The entire house had the look of a rotting vegetable. The ground was puckered up around the foundation. Years’ worth of rotted leaves and soil lapped at the rubblework stone walls. Mud piled up before the front door.

“We usually go in the back,” her brother Charlie explained.

Wenna opened the passenger door and was almost flattened by the stench in the air. She closed the door with the quickness of a reflex. Charlie had gotten out of the car already. He seemed not to notice or to care about the smell. Cautiously, second-guessing her own senses, Wenna opened the car door again. The stench remained. It was an unwholesome, poisonous odor. The bog had never smelled like that to her before. Bogs were, in their own way, exceptionally clean places, all the stink of vegetable death sealed discreetly away under the surface. There was something wrong with a bog that had a perceptible odor.

She was momentarily annoyed that Charlie didn’t offer to carry her bag to the door, until she noticed he was leaning on a cane that he’d gotten out of the back seat, his face wrinkled with an expression of intense focus. “The back door’s unlocked,” he said, before she could ask what had happened to him. This announcement was also the end of any conversation between them. Wenna carried her bag to the door.

Buy the Book

The Bog Wife

In the kitchen, it was the almost-comforting house-smell that she registered first: something between the musty paper-and-glue odor of an unkempt library and the putrid scent of vegetables left to rot in darkness. After a moment, her eyes adjusted. Every visible surface was so crowded with objects that Wenna could only register the whole as clutter. Even the stove was mostly covered, old magazines spilling from the mouth of a saucepan, a single burner perfunctorily cleared for use. Racks of dried herbs and greens hung from the ceiling, so long forgotten that they trailed dusty strands of cobweb; Wenna wouldn’t have been surprised to learn they had been harvested the summer before and left there through the winter. The floor was streaked with a palimpsest of dried boot prints. From one corner, a white possum regarded her warily.

“Did you know that was in here?” Wenna said with a nod to the animal. She had a suspicion that the possum was a full-fledged member of the household.

“It’s Nora’s,” Charlie said. He shifted uneasily from one foot to the other. “Eda said there was no point in cleaning, so.”

He was embarrassed; Wenna was not hiding her disgust successfully. “I’m sure it’s been difficult,” she said, at a loss for any other vaguely appropriate response.

“Sort of.” He cleared his throat, girding himself to say something else, but then Nora and Percy came thudding down the stairs.

Her siblings had gone through growth spurts and puberty in Wenna’s absence and become young adults. They seemed to Wenna to have uncannily grown into each other, even more alike now than they had been as children. Their upturned Haddesley noses and indignant sharp Haddesley chins; even the feathery mushroom-colored hair that they wore in a cloud around their ears. Only, Percy wouldn’t really look at her, and Nora was looking at her as if her gaze could fix Wenna in place.

“You came home,” she said, with a kind of awe.

“I can’t stay long.” Wenna was surprised and vaguely appalled by her impulse to disappoint her sister, but Nora’s happiness felt oppressive. No one was supposed to be so affected by her coming back. “Just for the burial,” she added, lowering her voice as if it were a secret that their father was right now lying in bed dying.

“I know.” Nora’s voice carried a defensive edge. She glanced sideways at Percy, as if checking to see whether he had noticed. Regaining herself, she asked: “Do you want something to eat?”

“What have you got?” Wenna hadn’t eaten since getting on the bus, but she was less than confident that anything passably edible could be prepared with the kitchen in its current state.

Percy went to the refrigerator, a 1980s behemoth that had been with the house since the Haddesleys, forty-some years late to the game, first acquired electricity. “Pickles,” he said. “Swiss cheese. Eggs.”

“We should make eggs,” said Nora. “Eggs are for breakfast.” She sounded as though she were reciting something she’d read in a book but had not personally experienced. “Do you want coffee, Wenna?”

“She can’t have both,” said Percy. “Not at once. There’s only one clean burner.”

“I’ll have whichever,” Wenna said, and she settled into a spindly little dining chair that she recalled from childhood. The kitchen table was from the same familiar set, but it was now so deeply buried in clutter that barely any of the tabletop was visible. As Percy and Nora negotiated the single functioning stove burner, she fidgeted with a paper box of spoons, some of them ornate and expensive-looking, others bent and tarnished and otherwise unremarkable. All of them glossed by dust.

Percy and Nora sat across from Wenna as she ate, their eyes politely averted, even their breaths measured. As if she were a wild animal they’d been lucky enough to stumble upon in its natural habitat. Only when the kettle began to shriek was their attention diverted. Nora rose and poured coffee for all three of them.

“If we had milked Matilde, you could have had milk,” she said as she set Wenna’s cup before her. “But Percy is supposed to do it, so—”

“I didn’t have time,” Percy insisted. “I had to do Charlie’s chores.”

“It’s no trouble,” Wenna said, to head off whatever meaningless bickering was brewing. At least that much had not changed. She looked down into the cup, at the grounds adrift on the surface. “By the way, what happened to Charlie?” she asked, putting off her first sip.

Nora’s eyes searched Percy’s as if he were responsible for the answer. Percy drummed his fingers impatiently on the table. “Is he all right?” Wenna heard the panic in her own voice. She hated that already she’d become entangled. She’d been in the house for ten minutes.

“Well,” said Nora. She hesitated. “Did you see the tree on the roof?”

“Of course.”

“The place that the tree fell was Charlie’s room.”

Wenna looked at Percy, who only nodded.

“And he got hurt,” Nora continued. “He can walk now, but he can’t really do stairs and he mostly stays in his room.”

“The room where the tree fell,” Wenna said, incredulous.

“He sleeps in what used to be the study now,” Percy clarified.

Wenna couldn’t even decide what to ask first. She felt as if she should have been told as soon as the accident happened, as if she had somehow been lied to, even though she would have said that she didn’t want to know. “What did he hurt?” she asked.

Percy and Nora exchanged glances again. Neither of them answered her question before Eda came down the stairs, bearing a tray piled with empty dishes.

It hurt to look at her older sister. In the malnourished light that the windows admitted, Eda might have been sixty instead of thirty-three. Her skin had the same waxy lusterless quality as Charlie’s. The dark half-moons beneath her eyes formed furrows down to her cheekbones.

Wenna didn’t know whether she was supposed to embrace her sister or shake Eda’s hand or take the tray from her, and in the end she did nothing, paralyzed by the sensation that she and Eda were about to resume a fight they hadn’t finished ten years ago.

“Wenna,” her sister acknowledged, as if she had been asked to identify Wenna in a lineup. Then, after a long and conspicuous silence, “Dad wants to see you.”

Wenna steadied herself in her chair. She had not prepared herself for the trial of interacting with her father outside of the mercifully scripted context of the burial rites. “Does Dad know that I’m here? I mean, did someone tell him that I was coming?”

“He knew that you were coming for the burial,” Nora offered.

“Right, but—”

“He might not be happy to see you,” Eda interrupted, sounding more exasperated than Wenna thought she had any right to be. “If that’s what you’re asking. He’s not happy to see me, most of the time, and I’ve been changing his bedpan for the past month.”

“I didn’t have to come out here,” Wenna said.

“Didn’t you?” Eda said, with a dismayed little huff of laughter. “Don’t go up there, if you don’t want to. Just know that he heard you downstairs and asked for you.”

* * *

Wenna ascended the stairs with the grim sensation that she was proving something. Her father’s bedroom was the first one to the left, the door open. She stood for a second in the hallway and absorbed that the figure on the curtained bed was really her father. It occurred to Wenna that she didn’t know what he was dying of. His skin had the same blanched waxy quality as Charlie’s and Eda’s, but worse. As she entered the room, his eyes narrowed, became unfocused, then regained their intensity.

“Tell Eda that I don’t want more peas,” was the first thing he said.

“I will,” Wenna said, too taken aback to protest. She took a deep breath, fortifying herself. It would have been easier if only he had been dead already.

Her father’s eyes drifted from Wenna’s face to the other end of the room, the opened door, the dark hallway. He wanted something other than her. “Easier for everyone,” he said dreamily, “if I am empty when I go.”

Wenna lowered herself into the dining chair at his bedside, awkwardly folding into her lap the worn old throw blanket that had previously occupied the seat. Everything in the room emanated a scent fainter but no less morbid than the rancid odor outside. “Empty?” she repeated.

“My stomach,” he said, assuaging any fears she might have had that he was becoming philosophical at the end of his life. “People shit when they die, you know.”

“Right,” Wenna said. “Do you think,” she ventured, knowing that she was being impolite but deciding that maybe they were past that now, “you’ll die today?”

“It must be soon.” He looked entreatingly at her. “I have dreamed,” he said, with urgency, “of meeting on the road a man walking with a cart pulled by a mare impaled on a post.”

Wenna crossed her arms to hide the gooseflesh that lifted on them. “I don’t know what that means,” she said firmly.

“I should have gone a long time ago,” he whispered. “It never was right, after her.”

Wenna’s throat closed as rage tightened her belly and her lungs. She could not think of one single thing to say that Alyson the therapist would have approved of. “I’m sorry that you’re dying,” she managed at last, staring ahead, inwardly cringing at herself for saying something so transparently insincere, when what she wanted to say was I am never going to forgive you, not even after you’re gone.

When she dared to glance over at him, his gaze was distant. “You cannot go back, you know,” he said, “to wherever you have been. They need you here.”

Wenna was perversely impressed. She should have known that the summons to bury her father was only a pretext. Of course she could not simply come back and then leave. She had been stupid to think that she was ending anything by coming here. But even her father could not possibly be so brazen as to think that on his deathbed he could make any demands about what she did or where she went after she had already squirmed free from the Haddesley noose once.

“What right do you have?” she said under her breath, not really wanting or expecting an answer.

“Tell me,” whispered Charles Haddesley with the rhythm of an incantation. “Tell me you will stay with them.”

Wenna lost her patience. “You can’t ask me for things! I came for the exchange. That’s all you get. And it’s more than you deserve.”

Her father’s look became urgent, almost wild. “I never hurt her,” he said imploringly. “You must know.”

Wenna’s stomach turned. “If you didn’t do anything to her,” she said, slowly, “then where did she go?”

Her father hesitated, and for a second Wenna felt a small gasp of hope that he was going to really answer her, that somehow there’d been a misunderstanding left for ten years uncorrected. But instead he exhaled, and a terse silence unspooled around them. He had no answer for her.

“Like I thought,” said Wenna, and she stood to go. She hesitated at the doorway, thinking how disappointing it was that those were the last words she might ever exchange with her father. She did not look back at him.

Excerpted from The Bog Wife, copyright © 2024 by Kay Chronister.