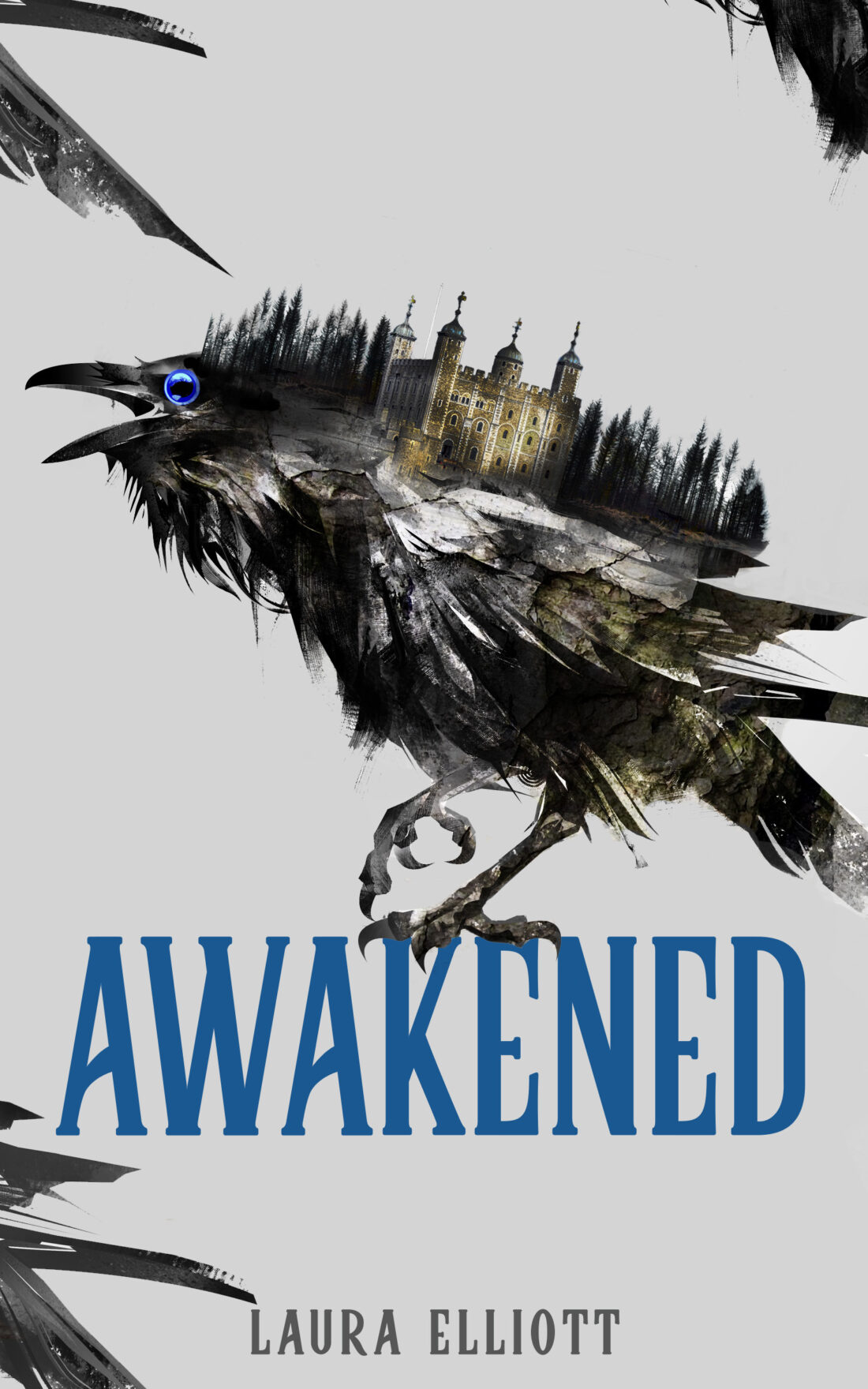

Awakened by Laura Elliott will be available June 10 2025 from Angry Robot Books.

From an exciting new voice in horror comes the tense and surreal novel Awakened. Exploring the extreme aftermath of induced global sleeplessness and the horrors of love amidst lost sanity, this is a perfect read for fans of The Girl with All the Gifts and 28 Days Later.

Funded by a benevolent but misguided billionaire, a group of scientists developed a neural chip to allow the population to turn off sleep. First used by the military, those fitted with the chip developed strengthen metabolism. In the space of a year, everyone had one. You could turn the chip off at will… until one day, you couldn’t. Deprived of the sanity that sleep brings, people quickly descended into madness, and the world changed—for the worse.

Now, marooned in the Tower of London, the surviving scientists struggle to find a cure in a new world, caged in by the screams of the Sleepless. Consumed by guilt for her part in the initial experiments, Thea Chares longs to know what has happened to her mother, whose illness had been the focal point of her previous life.

When two survivors, a man and a woman, stumble into the Tower, the seed of hope grows in the form of a new start. But all is not as it appears… the survivors display strange, dangerous habits and refuse to tell the scientists their names. As Thea finds herself inexplicably drawn to the man, life begins to spiral into a fever dream of hallucinations, violence and dark attraction, with a startlingly reveal waiting for them at daybreak.

Awakened is a dreamlike and gripping novel that will have readers questioning what’s real and what’s steeped in surreal until the very end.

Buy the Book

Awakened

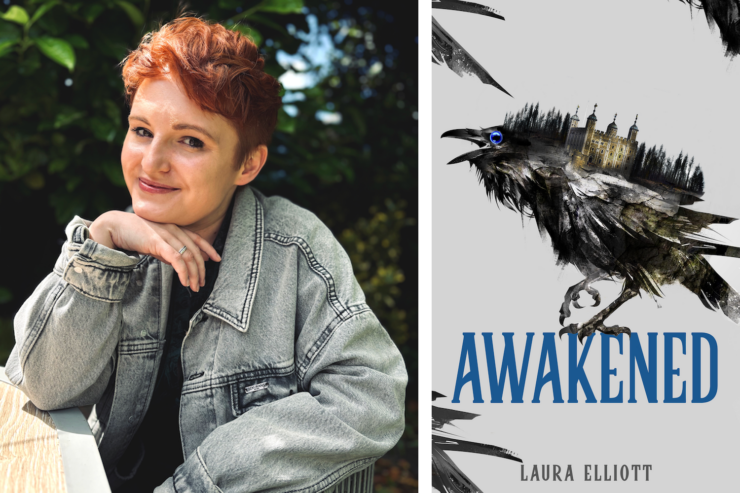

Laura Elliott is a journalist and writer on disability and health issues. Laura has ME and this has informed her writing and her career. She has written articles on disability and politics for The Guardian, The Metro, iNews and ByLine Times. Her stories have appeared in Strix Magazine, STORGY and Cloister Fox, and creative non-fic and essays in Boudicca Press: Disturbing the Body anthology, Monstrous Regiment: So Hormonal.

but in the minutes before dawn there is peace in the Tower and this moment is all that there is, with a Traitors’ Gate view over the dead city and the river at rush and the ravens, the ravens splitting the fog on dark wings while the two goats bleat in the stable and Thane’s lamp is lit, a will-o’-the wisp at Lanthorn which rises through the wet air and grows, grows in my mind to become a beacon of roaring fire and a candle for the dead, the dead who walk and are sleepless and are everywhere and nowhere, and now when the sun rises over London the fog burns away slowly, slowly, and then all at once, raising the curtain on my holy moment and a day that smiles with its teeth

March

2nd March

I’ve been an insomniac all of my life, but I’m not Sleepless and I won’t become Sleepless, just as long as the chips that were put into their heads never get put into mine. There’s little chance of that, since I won’t put the machinery into my brain and neither will Edgar and neither will the Professor, and we’re the only three left who could. I don’t want to be Sleepless, but insomnia is a treasured friend and it keeps me company during the long, dark quiet, during the deepening hours in which only I’m alive and awake and only Mother is here as my witness.

Mother, who lies in the spare room across the landing from mine, who sleeps on a double bed by the window just like mine, who has eyes that are just like mine and a smile that is just like mine, though I haven’t seen it for a long time. And perhaps there is something in this doubling that becomes clear to me only at night, when I walk from my door to hers and cross the threshold into this room of the sick, which, like all rooms of the sick, exists outside of time.

Mother’s room doesn’t alter with the ticking of the clock, and nor does it respond to the rising and setting of the sun. It persists apart from these comforting rhythms, a pocket universe in which the body is the world and the world is the body, eternal. The streets beyond these walls could burn and the seas could rise, and she would lie here just as she always does, waiting for me to arrive. Perhaps—an unnerving thought—she doesn’t wait for me at all. Perhaps her waiting is a state I’ve imposed on her, and only I anticipate these nights spent together in peace. But anticipate them I do.

The heavy velvet of the closed curtains. The dust that streaks them like moth tears, and the cardboard wrapped around the walls that I tape and tape in dubious configurations to protect her from the pain of sound. The darkness which has a texture, which grows substance and weight and form the longer I sit there in the chair by the side of her bed. I sit there in the night, and I feel the weight of gravity increase and draw down the darkness like a confectioner spinning sugar sculptures out of the absence of light. I sit there and I think. I think about sleep, and I think that, for once, I ought to try and tell you the truth.

4th March

We moved into the Tower of London during the frantic summer of 2055. At the time, the city was glutting itself on an excess of industry, and on every street there rang a swarm of tramping footsteps and lowing bodies packed together like cattle for the market. London was in its final bloom, but the impending collapse was hidden by a last long gulp of plenty. Looking back, there was no sense of dread in the air and no subtle suggestion that a disaster was approaching. In those final years, the prevailing emotion was one of exuberance and energy. We let the monster swallow us, and we were happy as we were digested.

Now expelled, that first summer has taken on a peculiar tone in my memory. Nostalgia colours the Tower’s walls in gold and the laboratory lights are dazzling, the contrast turned up so high that it hurts to look at too closely. If I close my eyes, I can still see us as we were—hastened, excited, flushed and fat with pride and purpose. A society of ignorants in bliss. Our most generous benefactor was the Anonymous Billionaire, he who had bought the historic site, repurposed it, and settled the Orex Corporation in its bowels.

Our laboratory is still situated on the first floor of the White Tower, in vast and ancient rooms that were once the royal apartments. I arrived there this morning to find Edgar and Professor Galen already at work. Our three lines of workbenches had been pushed to the walls and the machinery covered in protective sheets. This left only a great open space, save for a single patient bay behind a green medical curtain that drew my gaze like a shroud.

I watched the curtain, and I could almost convince myself that the curtain watched me.

“Courage, dear heart,” the Professor said. “All great discoveries are difficult. Let us not cower at the first sign of hardship.”

“She can’t help it,” Edgar told him. “She is a creature of pity.” He had dressed himself for the occasion in an embroidered waistcoat, a red cravat, and a bowler hat that Alison had unearthed in the warren of our extant storage. He reminded me less of the Lord he’d once been and more of a praying mantis, thin and wiry and creeping.

Before we could begin, we were interrupted by the febrile whirr of the lift, and Maryam wheeled herself in. She didn’t acknowledge us, instead taking up a spot by the door with a pile of knitting in her lap and the air of someone at protest.

“Doctor Bashir. It’s good of you to join us after all,” the Professor said. “Are you here to bear witness or are you participating today?”

“We’re all participating in this, Michael, whether we wanted to or not.”

“Does that mean we can count on your assistance?”

Maryam twirled a skein of wool expertly around her wrist and shook her shoulders as though casting off a chill. “I’m here for Thea. The two of you can do whatever you want.”

If the Professor was irritated by her dismissal, I wasn’t able to tell. He nonetheless affected an air of indifference and asked us if we were ready to start.

The truth, if I’d have been able to tell it to him, was that I was stuck in a peculiar state of anticipation and revulsion. That the thought of the next few hours filled me with primal disgust, which had manifested itself as an intense need simply to get everything over with. I didn’t know how to explain that to him, so I merely nodded, and then Edgar clapped his hands together and our patient’s shrieking split the air.

I wish now that I could describe the noise they make with any accuracy. I wish it because I am a scientist, and when a thing can be precisely described, it can at least be partially understood. The inability to quantify the sound, the utter failure of analogy, is almost as distressing as the sound itself. The pitch oscillates between ten and fifteen thousand hertz, swooping up and down the frequency scale every five seconds with a stridency that’s intensely painful. It clocks in at around 130 decibels, which is about the same level as a thunderclap. Perhaps that’s the analogy I’m looking for.

They scream a violent grief like a thunderclap.

But the screaming began—that was the point. The screaming began, and so we put our noise-cancelling headphones on, the Professor handed us all a computer tablet, and he typed on his own the words: Unto the breach. The projected screen on the wall behind him relayed the message, and Maryam retaliated with an image of a dog licking its own bollocks, which was impressive because I didn’t know the system could send pictures yet.

The screaming continued, and I arranged my desk. I placed the laptop in the centre, then the A4 pad to the right. I had a pencil and two black pens, just in case one ran out, and I put the tablet next to those. Then I helped the Professor put on his surgical gloves and tied his robe more tightly at his waist.

While this was happening, Edgar was setting up the video camera and placing the tripod next to my desk. It struck me that this meant our recordings would be from my perspective, and I didn’t know whether that made me feel powerful or afraid. All the while, Maryam knitted and watched us and said nothing.

Is everyone ready? the Professor typed.

Edgar had taken up his position by the curtain. In his bowler hat and waistcoat, he put me in mind of some wild conductor of a cabaret. I drew in a breath and nodded to the Professor, who nodded to Edgar, who looked to Maryam when her needles stopped moving. With a decided flourish, Lord Trevelyan stepped up to the curtain and drew it open. But it didn’t feel like a holy moment. It felt like a fall through the veil.

Excerpted from Awakened © 2024 by Laura Elliott