My first exposure to the writings of Camilla Grudova came via her 2017 collection The Doll’s Alphabet. As the title of that earlier work suggests, that collection abounded with stories in which inanimate objects—machines, costumes, and, yes, dolls—behave in ways that the reader might not expect. Those stories brought with them comparisons to the likes of David Lynch and Angela Carter; with respect to the latter, Grudova offered an expansive view.

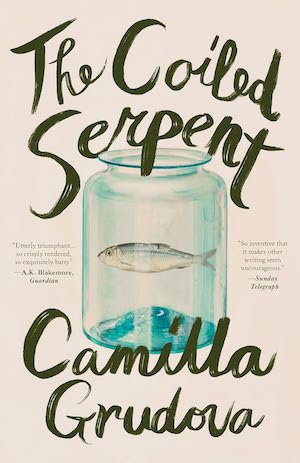

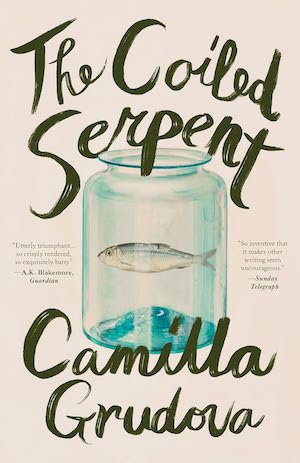

“I think fiction writers working today cannot avoid being influenced by Carter in some way, just as generations couldn’t avoid the influence of Eliot or Joyce,” she said in a 2017 interview. If Grudova’s earlier collection reckoned with some of the same themes as writers like Carter and Helen Oyeyemi (who’s cited in the same interview), her new collection The Coiled Serpent takes that approach and heads into uncharted territory. Or perhaps territories would be more precise: The Coiled Serpent is one of those collections in which an author showcases their range and offers readers a sense of surprise throughout.

That sense of surprise is bolstered by a related mood: one of dislocation. The narrator of the first story, “Through Ceilings and Walls,” has traveled to an isolated island from another country. Details on both the narrator’s point of origin and their destination are relatively scant, and those that Grudova does share often have to do with culinary practices. (This isn’t as random as it sounds.) There’s also an escalating sense of wrongness here, as when the narrator describes an unnerving site in the guest house where they’re staying:

At the guest house, I grabbed a pan and went to the bathroom to get water. It looked like there was a green olive stuck in the drain of the sink. I ran water from the tap on it to push it down, but it only quivered. I touched it—it was softer than an olive—and pressed on it. It quickly disappeared into the dark of the pipes.

Plenty of people can relate to finding something unexpected in their place of lodging. The fundamental unknowability of this substance, though, takes us into uncanny territory; by the time the story’s reached its unsettling conclusion, we’ll have proceeded much further in. There’s something of the social tension of Robert Aickman and Rachel Ingalls here, combined with a post-Cronenbergian sense of the visceral. Which is to say: This book is off to a promising start.

Buy the Book

The Coiled Serpent

This isn’t the only place where a living space behaves in a bizarre or sinister way. Later in the book, the back-to-back stories “White Asparagus” and “The Apartment” offer distinctive takes on domiciles where the laws of reality don’t seem to apply. In the case of the latter, that space is five rooms where clutter has pushed past the bounds of realism and entered outright surrealism, including a perpetually moaning “ancestral head on a plaque” and an assortment of possibly edible mushrooms growing in the bathroom, which might also contain a forest.

The first sentence of the latter story sets out the stakes in stark terms: “This is the story of six residents of the same apartment and how they all died.” In another collection, this might be the lead-in to a deftly-plotted crime yarn; in Grudova’s, the deaths are abrupt and the imagery is often disquieting, as when one character inspects vomit consisting of “red stains and silver fish scales.” One resident of the apartment hunts and kills slugs; another finds his body fused to a hat after surviving a violent assault. The residents of the apartment are relatively nonchalant about the omnipresent violence:

They buried him in the communal garden because they had no energy to carry him to the cemetery, and they also hoped his body would fertilize the nettles and other plants growing there that they had been subsisting on.

“The Apartment” is the penultimate story in this collection, and it features a few moments that echo other stories in the collection—it’s one of two stories in the book with a character named Taras, and other objects, such as fish tins, crop up elsewhere as well. This isn’t to say that these stories are meant to fit together seamlessly; I’m reasonably sure that they don’t. Instead, they play out like variations on a theme, the way you might hear a talented musician quote from a familiar melody in the midst of a larger improvisation.

“The Apartment” also echoes another motif found throughout this collection: stories that focus on people who share the same space—whether roommates, family members, or intimate companions. In the title story, Grudova introduces the reader to a trio of young men (Pax, Angelo, and Alexander) who share a drafty apartment in order to save money. That this apartment spans “three or four buildings” is the first sign of surrealism here; it won’t be the last.

The three men work in tech; they’re also somewhat insufferable, with a penchant for making obnoxious prank calls to random people in the city where they live. Pax in particular seems to be more insufferable than his roommates; there’s an unsettling line where Grudova mentions that Angelo and Alexander “had to stop [Pax] from beating up girls he thought were ugly.”

Gradually, Alexander becomes obsessed with a book titled The Coiled Serpent: A Philosophy of Conservation and Transmutation of Reproductive Energy. The trio expand their ambitions, leaving their jobs and starting their own tech company, and also becoming more and more obsessed with physical fitness and celibacy. And then, it happens: Alexander explodes while working out. Eventually Pax does as well. Angelo’s fate is left more ambiguous, though the fact that he continues exercising with the bloodied remains of his friend covering him seems troubling for numerous reasons.

The fixation on technology, the obsessions with physical fitness, the embrace of celibacy: It’s not hard to see “The Coiled Serpent” as a brutal satire of a certain type of tech bro. It’s also eminently understandable why this is the title story: In its offbeat perspective and unpredictability, it’s a synecdoche for the collection as a whole. You may not expect your destination when you begin each of these stories, but the journey is worth taking regardless.

The Coiled Serpent is published by The Unnamed Press.