Dear denizens of Chernograd and visitors to the city:

The Foul Days are nearly upon us! And what better time is there to re-familiarise yourself with Chernograd’s monsters: from the common upir to the cruel samodiva; from the prophetic yuda to the bloodthirsty karakonjul.

I’ll be honest: What won me over to Kosara, the protagonist of Genoveva Dimova’s Compendium of Monsters, wasn’t that she was a witch, or her cool fire magic, or that she had a penchant for gambling which too often got her in sticky situations. (Although those traits certainly didn’t hurt.) It was the fact that, as part of the Witch and Warlock Association, she created educational pamphlets every year to prepare citizens for the Foul Days, mailed them out to every household, and was deeply frustrated that not a single one of those people actually read the thing. That spoke to my little social-sciences heart.

For twelve days between the start of the New Year and the first roosters’ crow on Saint Yordan’s Day, while the new year is still unbaptized, monsters, ghosts, and spirits are free to roam the streets of Chernograd. Leading them is the Zmey, the Tsar of Monsters… and Kosara’s ex. Every year he preys on one unlucky young woman and sweeps her away to his castle to become his bride… and dead, within forty days.

Kosara is the rare exception who escaped, but now, every year, the Zmey hunts her down just to toy with her. After her attempt at eluding him goes wrong, she’s forced to trade away her magic (that gambling problem rearing its head) for a quick escape to Chernograd’s sister city, Belograd.

Belograd is just like Chernograd, except that a high, deadly, magically-infused wall keeps the monsters out of its borders and “safely” contained within Chernograd. It’s a lovely arrangement for the Belogradeans—their city is cleaner, higher-tech, and imports a steady stream of charms and artifacts from those pesky Chernogradeans—but not so much for everyone else. Instantly regretting her decision, Kostara chances a smuggler’s transport to return to Chernograd and get her magic back, but not without picking up a hanger-on in the form of naïve Belogradean detective Asen Bakharov.

Buy the Book

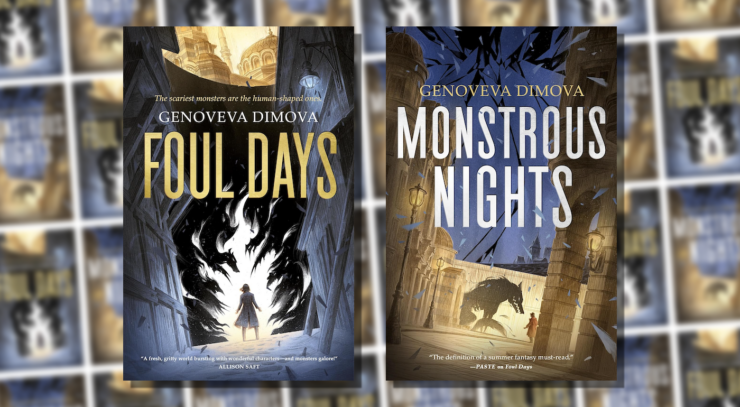

Foul Days

Kosara and Asen realize quickly that her magic has likely been sold to the Zmey—a twisted way of reuniting the two of them even now that Kosara rebuffed him. With her magic at his disposal, and that of his late brides, the Zmey plans to take on the Wall itself and tear it down. But even though he’s a monster, turning to a golden-winged dragon when he’s angry, his motives for doing so are so very human. Decades ago, the high council of mages stole the Zmey’s sister and transplanted her into the Wall so that her magic might fuel it, and the Zmey, like any good brother, wants to rescue her. The chaos, destruction, and death that would follow are… incidental benefits.

At the end of Foul Days, Kosara is able to turn the Zmey’s magic back on him and trap him inside the Wall. But after dragging secrets out of one another—that Kosara’s sister was torn apart by varkolaks (werewolves) and she blames herself, and that Asen’s wife was murdered by her father, a criminal kingpin—their relationship is on decidedly rocky ground. They part ways unsure if they’ll ever see each other again.

But events (and sequels) conspire otherwise.

Twelve days per year that monsters can infiltrate the human world. Those are the rules of Kosara’s world. But as Monstrous Nights begins, those rules unravel. Monsters like yuda and karakonjul slip through the cracks, and they’re encouraged by smugglers and corrupt politicians: the smugglers so they can chop up the creatures and sell their bones as tinctures, the politicians so they can gin up fear and mistrust. Asen and Kosara, investigating separately, are forced to cooperate again for the sake of both their cities.

Foul Days ends with stopgap measures: the Zmey buried in the Wall, and Kosara and Asen burying the feelings they don’t want to confront. Monstrous Nights is about digging them all back up and putting them to rest properly. Quite literally: Kosara’s dead sister is a ghost which lives in her house, and Asen’s dead wife has turned into a bloody banshee, and they can’t be left like that forever.

Author Genoveva Dimova hails from Bulgaria, and so the monsters of the duology are drawn heavily from Bulgarian (and wider Balkan) folklore. And while that’s not my expertise, knowing a smattering of Slavic roots and words definitely helped me spot some of the threads underlying the story. Chernograd and Belograd, for instance, mean “black city” and “white city” respectively—fitting for the city of monsters and the city without. And I wasn’t shocked that the Zmey erupted into a dragon because I knew that “zmey” (or “zmay”, depending on the language) is the literal translation of “dragon”.

Buy the Book

Monstrous Nights

I approached the series like a traditional fantasy, but what surprised me was how much more it was structured like a romance with fairytale elements. Yes, a major part of the story is discovering the world of Chernograd and its monsters, or the adventure-type quests of tracking down Blackbeard’s compass so he can take them across the rusalka-filled sea. But the emotional and character beats prioritize the romance between Kosara and Asen—their moments of self-discovery aren’t about unlocking hidden powers, but learning to let go of the people they loved before.

The Zmey might be the king of monsters, but he exists in the story as Kosara’s abusive ex. It’s his voice in her head, You’re useless. You’re weak. You’re nothing without me. You cheating hag, did you really think you could escape?, that she has to teach herself to quiet, and it’s his touch, alternating between tender and cruel, that she flinches at. Fighting him is never about the power differential between the two—it’s about Kosara gaining the emotional strength to stand up to him, to tell him no rather than meekly agree or keep running away.

Asen, in contrast, isn’t running from his past love—he’s clinging to it. He wears his wedding ring prominently around his neck, and though he’s clearly drawn to Kosara, he stops himself at every chance out of guilt and shame. It’s only worsened when the ghost of his wife appears, summoned out of her grave during the Foul Days: Even if her mind is a monster’s now, how can Asen let her go? Crossing the wall between Belograd and Chernograd, for him, is less about the fantastic people and creatures than about crossing the wall within himself and figuring out if he can love again.

Maybe I shouldn’t have been so surprised. We remember the beasts which populate fairytales, but the stories themselves are really about love. The Compendium of Monsters series is a modern-day fairytale, inventive and clever with its monsters and magic—and it, too, is ultimately about love.

Foul Days and Monstrous Nights are published by Tor Books.

Thanks for the review, but I am a bit disappointed by it (not by the book!).

Ideally, a review would tell me as a reader where the particular work lies in the speculative fiction landscape – what other books/movies/series it is like, what it is different from and how it differs; it if argues with some other works, etc. and ultimately, what ideas it defends/promotes/argues with/… All this avoiding spoilers, as much as possible. I would rather discover about the relatives of the character while reading the book.

I would have done this myself in the comments, but I just got the first volume before the holidays and haven’t managed to read it yet. But I have read other stuff by the author and liked it so I have quite high hopes.