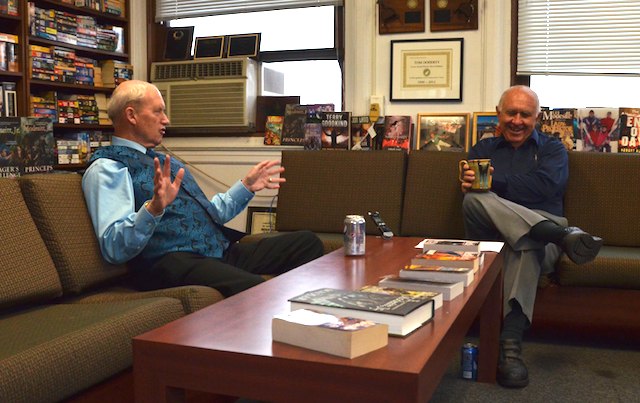

Who better to interview a living legend than another living legend? “Talking with Tom” is the first installment of a new Tor.com series in which Tor publisher Tom Doherty chats with one of the many authors whose careers he helped launch and shape.

Tom Doherty has been a central figure in genre publishing for decades. He is the founder, President and Publisher of Tom Doherty Associates, which publishes books under the Tor, Forge, Orb, Tor Teen and Starscape imprints. Tor Books, which he founded more than three decades ago, has won the Locus Award for Best Publisher every single year since 1988.

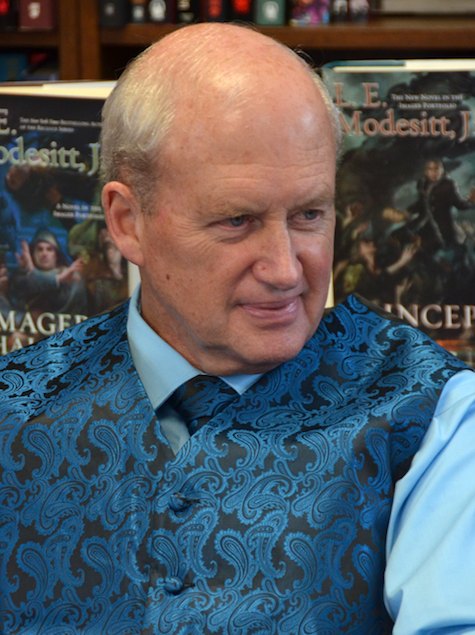

L.E. Modesitt Jr. is one of science fiction and fantasy’s bestselling and most prolific authors. He is best known for his long-running Recluce series, but has also written a large number of other series and standalone novels. Tor just published Mr. Modesitt’s sixtieth (!) novel, Princeps, earlier this year, and Imager’s Battalion, the next novel in his current Imager Portfolio series, is due out in January.

Please enjoy this fascinating conversation between Tom and Lee, two of the biggest names in science fiction and fantasy, each with multiple decades of experience in the field. Or, as Tom says at one point: “Boy, we go back a ways, don’t we?”

DOHERTY: How did you decide to take the time to write when you had such a busy life?

MODESITT: Because I always wanted to write. I mean, it’s as simple as that. I actually started out as a poet in high school. I published in small literary magazines for probably about ten years. I entered the Yale Younger Poet contest every year, until I was too old to be a younger poet, and I never got more than a form rejection letter from them. I think that was one of the critical turning points. Somebody suggested that I maybe should try science fiction because I’d read it ever since I was a kid, and so I did.

DOHERTY: Poetry is integral to a couple of your novels, too, isn’t it?

MODESITT: As a matter of fact, it is. Magi’i of Cyador and Scion of Cyador, two of the Recluce books, are actually linked together by an embedded book of poetry, which is critical to the resolution of the second book. I don’t know anybody else who’s done that.

DOHERTY: I don’t either.

After this brief discussion about L.E. Modesitt Jr.’s early poetry writing, the conversation turned towards his first science fiction sales as, primarily at the time, a short story author, and his transition from writing short fiction to novels.

DOHERTY: So, you sold your first short story to Ben Bova, and eventually Ben said, stop, I’m not going to look at any more of your short stories. You’re a novelist. Write novels.

MODESITT: That’s exactly true. But, of course, the problem was that I didn’t want to write a novel because I was only selling about one-in-four or one-in-five of the short stories I was writing. At that time, a novel was maybe 90,000 words, so I was thinking: “Do I really want to write a half million words to sell one novel?” Ben didn’t give me any choice.

DOHERTY: Ben was running Analog then?

MODESITT: Yes, he was. So, I started in on the novel, but by the time I finished it Ben had left Analog and Stan Schmidt wasn’t interested in what I was writing, so I had to find a publisher. I didn’t know anybody, and in those days you actually could go over the transom, so I started sending it out. I got rejected by a number of people, and it kept getting rejected, until all of a sudden it ended up at Jim Baen’s desk when he was the head of Ace. Jim said, or wrote actually: “This is really good, I want to publish it”, and he kept saying this every month for a year. And then, after a year, I got the manuscript back with a note saying: “This is really good. I really wanted to publish it and it’s really good, but it’s not my kind of book. Somebody will publish it.”

DOHERTY: It wasn’t his kind of book. I worked with Jim for a lot of years, too, and he was awfully good at a particular kind of science fiction. That’s where his heart was, that’s what he did well, and nobody did it better. But it wasn’t what you write.

MODESITT: I’m not sure there are too many people who write what I write.

DOHERTY: I don’t think there’s anybody who writes what you write. By that I mean as varied, as long, as productive. I don’t know anybody who has written as many pages over the last 30 years as you have at consistently high quality. You know, you write a page turner. Stories just grab you, they hold you. People come back for more. Your books stay in print. That’s in large part because of reader demand. If people weren’t buying them, we couldn’t keep them in print.

At this point in his career, Modesitt hadn’t sold a single novel yet. As the conversation between Tom Doherty and L.E. Modesitt Jr. continued, they discussed Modesitt’s first novel sales and how he ended up a Tor author.

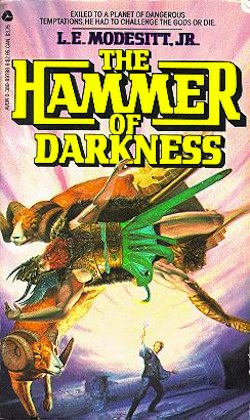

MODESITT: The next person I sent that manuscript to was David Hartwell, who was then running the Timescape line at Simon & Schuster, and he bought it. That was The Fires of Paratime, which got good reviews. Of course, the only problem was that, three months after it was published, Simon & Schuster folded the Timescape line. So I didn’t have a publisher again and a lot of people kept rejecting things. Then John Douglas, who had been David’s assistant at Timescape, ended up at Avon, and he wanted to buy it. They offered less, but nobody else was buying so I sold it to Avon and they published The Hammer of Darkness, with possibly one of the worst covers it could ever have had. I mean, it was good artistically, but it was a Conan the Barbarian cover. It basically had this picture of a goat cart being thrown across the sky and this little man in black at the bottom corner. Now, that scene actually takes place in the book, but it’s not really representative of what I do, so anybody who liked the cover wasn’t going to like the book, and anybody who liked the book wasn’t going to  pick it up because of the cover. You guys reprinted The Hammer of Darkness later with what I would call—and I’ll be fair about this—a science fiction cover, nice but nondescript, and it sold four times as many copies as a reprint as it did in the original, just because the cover was better. But again, the problem was that John Douglas wanted to buy another one of my books, but then Hearst acquired Avon and froze submissions for three years, so again I had to look for another publisher.

pick it up because of the cover. You guys reprinted The Hammer of Darkness later with what I would call—and I’ll be fair about this—a science fiction cover, nice but nondescript, and it sold four times as many copies as a reprint as it did in the original, just because the cover was better. But again, the problem was that John Douglas wanted to buy another one of my books, but then Hearst acquired Avon and froze submissions for three years, so again I had to look for another publisher.

DOHERTY: I think it was fate, see? I was supposed to publish you.

MODESITT: Well, it’s pretty obvious that that was the case because David Hartwell came back up and said, “Hey, I’m at Tor. I can buy your next novel.” I said, “Fine.”

DOHERTY: You know, I actually made the first mistake unknowingly, because Jim Baen was working for me when he didn’t publish your first book.

MODESITT: Well, I didn’t know that.

DOHERTY: Yeah, I was publisher of Ace, and Jim was our science fiction editor.

MODESITT: Okay, I’m going to give you another nasty one. One of the people who rejected my first novel is now working as a consulting editor for you. That’s Pat LoBrutto.

DOHERTY: Well, Pat LoBrutto was at Ace, too, in those days.

MODESITT: This was when he was at Doubleday. Yeah. I remember who rejected me, let me tell you.

The next phase of the conversation was something that can really only result when you get a couple of people with several decades of industry experience together.

DOHERTY: Of course, when I became publisher of Ace, that was the year that the Science Fiction Writers of America discontinued the publisher Hugo. I could almost take that personally. Pat LoBrutto, who was at Ace then, went over to Doubleday, and I brought Jim Baen in from Galaxy. Jim’s heart always was in short stuff, though. He loved military science fiction, but he really loved magazines and the magazine approach. Eventually, well —I liked much of what Jim did, but I didn’t want it to be all we did.

MODESITT: Well, but that’s what he’s done at Baen, in essence.

DOHERTY: And it worked out fine because, when I brought David in from Timescape, Ron Bush had gone from publisher of Ballantine, where he had renamed the Ballantine science fiction Del Rey after Judy?Lynn, over to Pocket Books. As president of Pocket Books, Ron tried to hire Jim away, because Ron, having come out of running Del Rey, was very high on science fiction and wanted a strong science fiction line over there, but Jim didn’t want to go to work for a big corporation. I knew Ron quite well over the years, so I called him up and said “hey Ron, look, Jim doesn’t want to join a big corporation, but he’s always dreamed to have his own company to do things in the way he saw them. And he’s a fine editor. You’re trying to hire him, you know that. Suppose we make a company for you to distribute, and you’ll be the distributor and we’ll be the publisher. We’ll make what we can make but you’ll make a guaranteed profit on the distribution.” And he thought, why not?

MODESITT: Well, it’s still working for him.

DOHERTY: It’s still working, and that’s how we started Baen Books. I actually gave Jim the inventory to start Baen. I allowed him to take any authors who wanted to go to the startup with Simon & Schuster, any authors that he had brought in that he had worked on. And that was the initial inventory, the first year of Baen. So they would have been Tor books.

MODESITT: I don’t know. I think it worked out better for all sides.

DOHERTY: I think it worked out just great. Baen is still a healthy company doing nicely under Toni [Weisskopf], and, hey, I’m still a partner over there.

MODESITT: Sort of the silent partner.

DOHERTY: A very silent partner. They do it all themselves. It would be conflict of interest to get too involved, but it’s fun to be part of it even on the outside.

MODESITT: Anyway, that’s the long story on how I—

DOHERTY: Decided to write a novel?

MODESITT: —ended up writing novels. What was I, about the fourth or fifth author you signed? I wasn’t the first. I think Gene Wolfe was one of the first.

DOHERTY: Actually, the very first was Andre Norton with Forerunner. But Gene Wolfe was, I think, the third. Poul Anderson, I think, was the second—no, I’m sorry, it was Gordy Dickson. Boy, we go back a ways, don’t we?

From that point, the conversation turned to L.E. Modesitt Jr.’s incredibly prolific career as a fantasy and science fiction novelist, and the way his long and varied professional career outside of SF&F influenced him as a writer and person.

MODESITT: If I recall correctly, I think I signed my first contract with Tor in 1983.

DOHERTY: And you’ve published 60 novels, right?

MODESITT: Yeah, Princeps is the sixtieth.

DOHERTY: Over just a little more than 30 years.

MODESITT: Yeah.

DOHERTY: Yeah, wow.

MODESITT: I only did about one novel a year while I was working full time, but since 1993 I’ve averaged two and a half books a year.

DOHERTY: We’ve noticed, and we’ve loved it. You move back and forth between fantasy and science fiction. How come?

MODESITT: I like them both, and you can do different things with each genre

DOHERTY: Yeah.

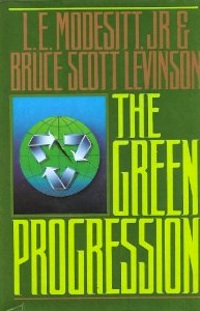

MODESITT: You also have the unenviable distinction of publishing the worst?selling book in Tor’s history of mine.

DOHERTY: Well, since we’ve published all your books, we had to publish the worst selling.

MODESITT: No, it was the worst selling book of all your line.

DOHERTY: I don’t believe it.

MODESITT: I do. According to my royalty statements, The Green Progression sold 392 copies in hardcover.

MODESITT: I do. According to my royalty statements, The Green Progression sold 392 copies in hardcover.

DOHERTY: Oh, my god. Did we do a simultaneous paperback? I don’t remember.

MODESITT: You did a follow?up paperback because you didn’t believe it would sell that badly in paperback. You printed 20,000 paperback copies, and you sold 2,000 of them. So I can claim being both one of your bestsellers and one of your worst sellers. I think one of the reasons for this ties into what I was talking about in terms of fantasy versus mainstream or even science fiction. In fantasy, I can take a really knotty ethical problem and place it in a somewhat less real setting. I try and make my settings as real as possible, but it’s not a culture that’s recognizable as our culture, so I can set that problem up in such a way that people can look at it much more objectively. When you get things too close to people’s preconceptions, and I think The Green Progression unfortunately proved this, nobody wants to look at it. It hits too hard and it’s too close to home. The Washington Times gave The Green Progression a review that said something to the effect of “this is one of the best explorations of how politics really works that’s been written in years.” Now, that’s not a bad review, but people didn’t want to see really how things worked.

DOHERTY: The real truth about politics.

MODESITT: The real truth about politics is that it’s both more deadly and less obvious than anybody wants to admit. I knew a lot of people in the intelligence community. As a matter of fact, one of my neighbors was the duty officer at the CIA on the night of the Bay of Pigs. But I don’t know of a single intelligence agent of any country who was ever killed in Washington, D. C., despite what all of the movies say. On the other hand, I could not count the number of suicides. Washington will basically dry up your living, alienate you and your spouse, keep your kids from having any friends, and make sure you don’t work in your field ever again. But they won’t kill you. That’s too kind. Nobody wants that kind of hard, gritty, indirect truth in a book. It’s not suspenseful. It’s not thrilling.

DOHERTY: You know, I don’t think anybody writing in fantasy or science fiction approaches your background for such a thriller. You were director of a congressional campaign. You were director of legislation and congressional relations for the Environmental Protection Agency. You headed a staff for a Congressman. You have an absolutely amazing background, and experiences that would give you a perception that nobody else writing in the field has.

MODESITT: Much of my writing about politics in different cultures is drawn out of that. I’ve often said that there’s no one thing that I do or have done that is particularly unique. There have been a lot of other authors who were in the military. There have been a few others who were pilots. There have certainly been a lot of other people who were in politics or served congressional staffs. There have certainly been other economists. There have certainly been other people who have had three wives and eight kids and lived all over the country. Or who have written poetry. Et cetera, et cetera. But, I honestly can’t say that I know anybody who’s come close to that kind of range, and I think that enables me to put a certain amount of depth of experience behind what I write that an awful lot of writers just don’t get. And one other tremendous advantage I had, even though at the time I didn’t think it was an advantage, was that I didn’t even try to write a novel until I was almost 40, so I had a certain amount of life experience before I started writing novels. As we were discussing earlier, I made an awful lot of mistakes in short fiction. I’d made enough mistakes in short fiction that, by the time I got to novels, I didn’t make as many.

Much of this incredible range of experience went into, and is still going into, L.E. Modesitt Jr.’s longest, most famous and most popular series, the Saga of Recluce. As the conversation between Tom and Lee continued, the focus turned to the logic behind the series’ magic, as well as the series’ unusual chronology.

DOHERTY: Your biggest and most popular series for us is Recluce. The heart of Recluce is the need for both chaos and order. Care to…?

MODESITT: Well, that’s true, although the magic system is a lot more involved than that.

DOHERTY: Oh, absolutely.

MODESITT: I actually wrote an article about this. It was published in Black Gate magazine about four years ago, detailing how I came up with the system.

DOHERTY: Oh, I didn’t see that.

MODESITT: Well, I think you’ll have a chance to put that in print sometime in the future.

DOHERTY: Good.

MODESITT: I won’t go into it now. The details are very scientific. None of it, of course, appears in the Recluce books, because that culture wouldn’t have the vocabulary for it, but I designed it that way so I’d know what was possible and what wasn’t under that logical system. It’s really more the question of balance. Basically, if you look at our universe, there’s a certain balance between, if you will, matter, dark matter, and what have you. Things have to balance or they don’t work—call it the law of conservation of energy and matter. I figured that, in a magical universe, you’d have to have something of the same operation there. Basically, if either one had too much power, it would either end up in total stasis or it would end up in total destruction. That was the basic concept why, although order and chaos can fluctuate locally so to speak, overall they have to balance. If one gets too far out of balance, the other’s going to swing back and right the balance—sometimes with catastrophic impacts, as several of my characters have found out across the novels.

DOHERTY: Fans write to us, and I think they’ve written to Tor.com, wanting to read Recluce in chronological order. You believe that they should be read in the order in which you wrote them.

MODESITT: Mostly. I realize that there are some readers who are just so, shall I say, chronology-oriented and stuck on that that they can’t read it in any other way, so I have made available a chronological explanation, or a chronological order, of each of the books for anybody who wants to know what that chronology is. Still, for most readers I think it’s better to start with The Magic of Recluce, because I think it’s an easier introduction. Chronologically, right now, the first book is literally Magi’i of Cyador. And, yes, it makes sense, you can read it as a stand-alone, but you miss a lot that is explained in The Magic of Recluce. For those who are chronological nuts, I’ll send you a copy of the chronology and you can read the series in that order, but the only problem is that I’m still writing Recluce books, so there are going to be other books that will sort of get pushed into that chronology as we go along. I don’t want to say much about the Recluce novel I’m working on now because I’m only 12,000 words into it, and that’s a little early for me so say much about it except, yes, there is another Recluce novel.

DOHERTY: And you especially don’t want to say in what chronological order—

MODESITT: No, not yet.

At this point, the conversation turned towards L.E. Modesitt Jr.’s newest fantasy series, the Imager Portfolio. (An overview of the first three novels in the series can be found here, and reviews of Scholar and Princeps are here and here. Imager’s Battallion, the newest addition to the series, is due out in January 2013.

DOHERTY: Your current series is The Imager Portfolio.

MODESITT: The Imager Portfolio in a lot of ways is a very, very different series from anything that I’ve seen, and certainly anything that I’ve done, because the idea is that under certain conditions, somebody can image something into being by mental visualization. But it’s not free: half of all imagers die before they reach adulthood because it’s such a dangerous profession. There is only maybe one person in half a million that have that particular talent, so it’s not something that can be caught and mass-produced. In the world of Terahnar, there’s been a very slow progression from, shall we say, low tech to, in the first three Imager books, a culture that’s roughly analogous to 1850s France, except electricity is not as developed and steam is more developed. There’s tremendous tension between the imagers and the rest of the population, so most of the continent’s imagers are still fugitives in hiding, but in one nation imagers have somehow become institutionalized in a way that protects their safety and also benefits the culture. It’s a very tenuous balance.

DOHERTY: Did your background in politics go into this?

MODESITT: Yes, because the culture is literally emerging into what I would call early Industrialism from something like a Renaissance culture, so you still have the High Holders, who are the equivalent of nobility; the Factors, who are the emerging middle class; the class unions; and the balancing force between those three are the imagers. So you have this four?way political interplay, which is something that, again, I don’t see other people playing with. You have a pseudo-democracy in the sense that each of them has votes on the council that rules the country. In the period when the first three books take place, it’s becoming very clear that the nobility can no longer maintain their preeminent position in terms of the social forces. And of course we have a young imager, who is caught in this particular position at a time when both the nobility and other nations are really concerned about Solidar. So in these three books I’ve basically woven internal conflict, external conflict, and personal conflict together. Unlike a lot of fantasies those first three books, with exception of one small episode, all take place in the capital city. There are no quests. There’s nobody running anywhere. It’s all an understated thing, and there are a lot of aspects to it—one of which is that, because of what imaging is, the culture’s much more indirect, meaning the conflicts are not necessarily always obvious.

DOHERTY: And then you jumped back in time, chronologically.

MODESITT: Yes, after the first three Imager books, I did something that always drives my fans nuts: I asked the question “okay, I sort of sketched in the back history, but how did this all get to this point?” So the next five books, which began with Scholar and then go to Princeps, deal with the unification of the continent of Solidar, which at the time of the first three books, is an island continent. It’s just one country, but at the time, at the beginning of Scholar, there are five warring nations. I had always made a vow I that I would never write more than three books about a given character, and for 30 years I kept to it. Then I got to these books, and when I got about halfway through the third book I called up David and said “I can’t do this in three books. It’ll probably be four.” I got a half book further on, and I called David up and said “it’s going to be five. I promise you no more than five.” I delivered the fifth book last month. The first three books are Imager, Imager’s Challenge, and Imager’s Intrigue, and the second five are Scholar, Princeps, Imager’s Battalion, Antiagon Fire, and the last one I just delivered is Rex Regis. So, that’s the background on that.

Towards the end of the conversation, Tom Doherty and L.E. Modesitt Jr. discussed a forthcoming stand alone science fiction novel and its connection to a short story published earlier this year on Tor.com.

DOHERTY: And then there’s The One-Eyed Man.

MODESITT: Yes, there’s one other book that is in the works, which will be coming out next year from Tor. Earlier this year, David Hartwell put together a project for Tor.com called the Palencar Project. There was a work of art by John Jude Palencar, which is an adaption of, I guess, Wyeth’s Christina’s World in a fantasy setting, showing a woman on an endless plain, her back to you. That’s in the Wyeth painting with the interesting skyline, but on the Palencar painting, there are dark clouds that look like tentacles and suckers and what have you. David insisted that the five authors who were doing the Palencar Project write a science fiction story—not a fantasy story—based on that artwork. Well, I got rolling on it, and I kept writing and writing, and all of a sudden I realized I had 12,000 words in on this thing and was nowhere close to being finished.

DOHERTY: Back to what Ben Bova was saying in the beginning.

MODESITT: So, I wrote about a 2,500?word short story, which was published on Tor.com as “New World Blues.” It was actually the lead story in the Palencar Project. After I wrote another Imager book, I went back and finished the longer work. It started out as a novella and ended up being a fairly hefty science fiction novel, which is The One?Eyed Man and will be out about a year from now, as a matter of fact, on the publishing schedule. The story and the novel are both based on the same artwork, so earlier I suggested that Tor might put them both in the same package or do something to tie—

DOHERTY: Yeah.

MODESITT: Because you can prove that even the same author can have two different takes on exactly the same image, and since the short story “The New World Blues” is only about 2,500 words, it’s not going to measurably add to the cost of the printing, but it might give readers a little bit of a bonus.

And there you have it: a wide-ranging discussion between Tom Doherty, the publisher of Tor Books, and L.E. Modesitt Jr., one of his most prolific and successful authors. Stay tuned for future installments of “Talking With Tom”!

Stefan Raets reads and reviews science fiction and fantasy whenever he isn’t distracted by less important things like eating and sleeping. You can find him on Twitter, and his website is Far Beyond Reality.