The emergence of the Hyrule Historia, out on January 29th from Dark Horse Comics, was meant as a pleasant retrospective for The Legend of Zelda video game series, but ended up making a little history itself. Made available for pre-order in early 2012, it immediately knocked Fifty Shades of Grey off its perch as the number one bestselling book on Amazon.

So how did that happen?

(Note: Spoilers ahead for Skyward Sword.)

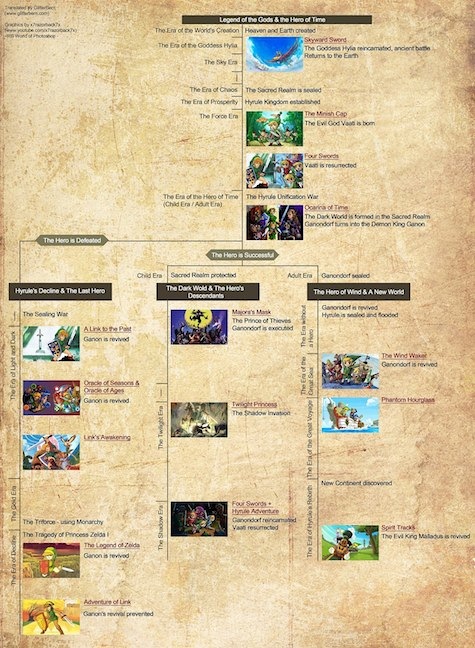

For Zelda fans, the book promised official validation of a theory that they had been constructing since about 2002: that the 15 individual video games in the series were actually taking place in the same timeline, stretching all the way to the original eponymous installment, which was released for the Nintendo in 1986.

The basic plot of all Legend of Zelda games is this: You are Link, a silent protagonist in a sleepy village suddenly thrust into a battle that will determine the fate of Hyrule, the fairytale kingdom you inhabit. A black-hearted monster, often going by the name Ganondorf, plans to conquer the land and plunge it into darkness. More often than not, this plan involves kidnapping Princess Zelda.

The macguffin often being fought over is a power called the Triforce, which consists of three parts: one of Power, one of Courage, and one of Wisdom. You, Ganondorf, and Zelda tend to embody these three parts, and as events progress to a final showdown, it becomes clear that this is a struggle that is destined to repeat over and over and over. (Hence the many games in the series.)

As a result of the timeline revealed in the Hyrule Historia suddenly games that players had assumed were simply different interpretations of one basic struggle were now different installments in a long, building mythology.

The timeline was constructed by Legend of Zelda series producer Eiji Aonuma and, once revealed, proved to be far more complicated than fans had previously suspected. The games didn’t depict just one long chain of events. Rather, they depicted a single chain of events that then broke off into three separate timelines, all of them depicted by legitimate installments of the video game series.

We had been playing a saga this entire time, the creators revealed. Albeit a saga retroactively created.

[Update! Kotaku has the English version of the timeline.]

The timeline itself was leaked in early 2012, but the more detailed mythology that fleshes out that timeline is contained within the Hyrule Historia itself, making it a prized item by fans of the series.

About one third of the book is dedicated to the details of stitching together the various games into one chronology. Aside from Skyward Sword, each game gets about 3 pages explaining the events of that game; stopping for little sidebars that theorize on whether a tool, sigil, or something else was inspired by events in a previous game. The evolution of the various races of beings that pop up in the games, like the Zora, the Goron, the Kokiri, and more, is tracked, and the events of each game are depicted as affecting and being affected by the other games. In the end, it hits the Fantasy Fan Detail Porn spot very nicely.

The explanatory text itself is very light, which matches the sentiment in producer Eiji Aonuma’s foreword. He is happy to present the timeline, but cautions that it shouldn’t be taken as strict dogma, as Zelda games are created with gameplay foremost in mind, not story, and a new Zelda game could land anywhere in the timeline, changing the context of the games around it. It’s a good warning to give, as a reading the details in the Historia makes it obvious that while there are a few notable guideposts in the timeline itself, there’s a LOT of wiggle room otherwise. As you continue to read through the details of the timeline it also becomes clear that the timeline itself doesn’t consistently adhere to its own logic*, meaning you’ll only drive yourself mad trying to make the timeline a rigid, cohesive whole.

*For example, the timeline splits after the events of Ocarina of Time, but not after the events of Skyward Sword, which seems odd since the same circumstances occur at the end of both games.

The rest of Hyrule Historia is taken up with an exhaustive and illuminating supply of draft sketches from all of the games in the line. A mini-manga closes out the book, which I found largely rote and unexceptional, but that’s alright. By the time fans get to that point, the book has already given them what they’re looking for. (Or as much as it’s going to give them.) The manga is a pleasant afternote.

The Historia should definitely satisfy hardcore Zelda fans. It provides a rich new context within which to view these games, evoking the same sense of exploration that the games themselves do, while leaving plenty of intriguing gaps for the imaginative.

Casual fans of the series should be warned that they won’t find much to keep their interest. The sections on the games I hadn’t played, like Four Swords and The Minish Cap, couldn’t hold my interest, and if I hadn’t hustled to finish Skyward Sword before reading the Historia the whole book might have fallen flat.

Where the book might also fail to satisfy is with hardcore fans of the series who are also avid readers of epic fantasy. (A crossover of interests that one assumes is probably fairly extensive.) Perhaps the most fascinating aspect of the Hyrule Historia is how the retroactive timeline essentially turns the Zelda games into an epic fantasy series, with all of the expected narrative tropes that this implies.

It’s unlikely that this was actually the intention of the creator and producer of the games, and Aonuma’s foreword eagerly underlines that the series should still not be viewed under this light. Regardless, fans of epic fantasy won’t be able to help but see the same underpinnings from their favorite book series now present in the Zelda games.

Aonuma and company may not have been aware of this when crafting the Historia, and this may become the most controversial aspect of the timeline and mythology presented in the book. If you’re essentially retconning these games into one story, a story with the same tropes as other epic fantasies, then fans are going to want a massive amount of detail. Epic fantasy is held to a joyful scrutiny that is unrivaled by other genres of fiction, and if you don’t provide the detail, then your fans will. The Historia doesn’t provide that detail, and in a lot of cases simply can’t without losing the fluidity that allows Nintendo to keep releasing new Zelda games.

It’s an interesting spot that the Historia puts this famed video game series in. The Zelda games, even at their most story-heavy, are essentially fairytale Indiana Jones-style adventures. They don’t hold up to scrutiny and you could make a good argument that they shouldn’t have to; that the point of the games is to give you something new to explore for a fun 50-ish hours.

Now they exist within a framework that invites more detailed scrutiny, and while this is also essentially something fun and new to explore, this new territory comes with different and more demanding expectations. Most likely, the creators behind Zelda will manage these expectations with a light touch.

But should they? Would The Legend of Zelda be more interesting if it became as richly detailed as The Lord of the Rings or The Wheel of Time?

I don’t know the answer to that question, and it’s not a question I would have ever thought to ask before reading the Hyrule Historia. But I will never look at The Legend of Zelda the same way again, and that is a fascinating accomplishment for a companion book.

Chris Lough is the production manager of Tor.com and had to grow into an adult before he was able to beat Zelda II: The Adventures of Link.