In the comments to Sleeps With Monsters: Epic Fantasy is Crushingly Conservative? one of the participants suggested that, if epic fantasy is held to be conservative (the discussion on what constitutes epic fantasy and whether or not it is conservative remains open), perhaps we should discuss whether urban fantasy is “crushingly liberal.” For the sake of alliteration, another commenter suggested licentiously liberal—so that’s what we’ll argue today.

Let’s start from the same principles as we did last time. How do we define “urban fantasy”? What counts as “liberal”? Liberal, it appears, possesses a straightforward definition, at least according to the dictionary.

a. Not limited to or by established, traditional, orthodox, or authoritarian attitudes, views, or dogmas.

b. Favouring proposals for reform, open to new ideas for progress, and tolerant of the ideas and behaviour of others; broad-minded.

But we have more than one way of defining urban fantasy. We may define it as it is presently used as a marketing category—to sketch a brief description, fantasies set in the contemporary or near-contemporary world, usually in large cities, featuring supernatural creatures, frequently told from the point of view of a character engaged either in vigilantism or law enforcement, sometimes both, and often but not necessarily featuring romantic/sexual elements. Into such a category we may fit the work of Laurell K. Hamilton, Jim Butcher’s Dresden novels, several books by Tanya Huff, the work of Kim Harrison, of Kelley Armstrong and Ilona Andrews, and Mike Carey’s Felix Castor novels, among many others. We may trace the roots of this subgenre to the 1980s, to Emma Bull’s War for the Oaks and Charles de Lint, and include in it the racecar-driving elves of early 1990s Mercedes Lackey.

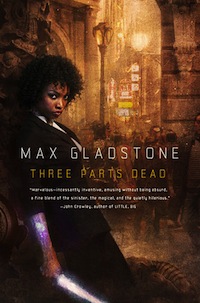

But we may in addition define it with particular reference to its urban nature, as a fantasy primarily focused on the city, the myths, fears, communities and alienations of civic life, modern or not. The city, the idea of the city, occupies a central locus in human history and thought. Its role is more important than ever in an age where an ever-increasing majority of humans live in cities—by 2030, 92% of people in the UK and over 60% in China, some projections say. I’m inclined to argue that some second-world fantasies, like Max Gladstone’s Three Parts Dead or Michelle Sagara’s Elantra novels, or Pratchett’s Discworld Ankh-Morpork novels, enter so far into this urban conversation, and find the idea of the city so central to their identities, that not calling them urban fantasy seems a foolish exclusion.

We may suggest a taxonomy—or at least a tag-cloud—of urban fantasy as follows: second-world, historical, contemporary or near-future, investigative, vigilantist, political, soap-operatic, near-horror, romantic, humorous. Within the greater umbrella of “urban fantasy” as I choose to conceive of it, then, it’s clear that there are a wide range of possible moods, themes, and approaches. But is it open to new ideas for progress?

If we had framed the question: is urban fantasy progressive in the political sense? (i.e., does it favour or promote political or social reform through government action, or even revolution, to improve the lot of the majority), I should have to argue in the main against: popular fiction is seldom successful in revolutionary dialectic. Nor, for that matter, has urban fantasy commonly been culturally progressive: its gender politics may perhaps improve slightly over those historically typical of fantasy in a pastoralist setting, but true progressivism, particularly in contemporary investigative/vigilantist urban fantasy, is often hamstrung by authors’ reliance upon Exceptional Women narratives. As a subgenre, its racial politics are as progressive as the rest of the SFF landscape—which is to say, not very, and prominent popular examples are not common.

Urban fantasy is easier to define than epic fantasy:* its semantics are more tightly bounded. But is it easier to assess urban fantasy’s relationship with established norms and authoritarianism? Can we actually accurately call it liberal, much less “crushingly”—or even licentiously—so?

Over to you, Gentle Readers. Over to you.

*Although I’m tempted to suggest a tag-cloud taxonomy for epic: mythic, involved in the fate of nations, involved with godlike beings or powers, not limited to one physical location, not limited to one viewpoint character.

Liz Bourke blogs and tweets, and reads more books than she really ought…