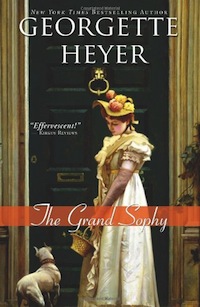

By now entrenched in the Regency subgenre she had created, for her next novel, The Grand Sophy, Georgette Heyer created a protagonist able to both challenge its rules and manipulate its characters, and a tightly knitted plot whose final scene almost begs for a stage dramatization. The result is either among her best or most infuriating books, depending upon the reader. I find it both.

The eponymous protagonist, Miss Sophy Stanton-Lacy, stands out from Heyer’s previous heroines in many respects. For one, although her direct control of her finances is somewhat limited, and a fortune hunter agrees with her assessment that her fortune cannot be large enough to tempt him, she is financially independent, able to buy and outfit her own expensive perch phaeton and horses and stable these horses and another riding horse, Salamanca, without blinking. She can also finance a lavish ball, complete with the band of Scots Greys even if her cousin insists on picking up the bill for the champagne. And if for any reason she has any unexpected expenses, she has jewelry to pawn.

This immediately puts her in a more powerful position than most of Heyer’s other heroines, who tend to be poor. It also changes her relationship with the hero. Sophy’s love interest has certainly inherited some wealth (the idea of a financially indigent hero was not something Heyer could contemplate in her escapist romances), but his finances are tied to a nearly bankrupted family and failing estates, making Sophy one of the few Heyer heroines to be more financially free than her hero.

To this, Miss Stanton-Lacy adds something else: her mother is long dead, and her father more than indulgent, allowing her a degree of independence mostly unknown to Heyer’s other wealthy heroines, who typically remained under the strong and unhappy control of relatives. Running her father’s household has also left her with a remarkable self-confidence and insight into people, only bolstered by the various adventures she lightly alludes to—Spanish bandits, chats with the Duke of Wellington, entertainments in Portugal and so on. It has also given her the irresistible urge to manage other people’s lives.

As another commentator noted in the discussion of Regency Buck, to a large extent, Sophy is essentially, Jane Austen’s Emma, with her independence, social standing, large fortune, and desire to arrange the lives of other people. With just two exceptions. One, Sophy, even wealthier than Emma, and on excellent terms with some of the leaders of Society in England, can dare to go against social conventions: buying a sporting phaeton meant to be used by men; riding a stallion; driving down a street where ladies are not supposed to drive, and above all, carrying, and knowing how to use, a gun. And two, Sophy, greatly unlike Emma, is almost always right. Her main flaw—apart from her propensity to manipulate people—is her temper. And that is a bit more forgivable than Emma’s sanctimonious misjudgments, especially given a few of the incidents that set her temper off.

Right. The plot. Sophy arrives at the home of her aunt and uncle and many, many cousins. The uncle, alas, is friendly and jovial enough, but also a spendthrift, a gambler, and a womanizer. As a result of the spending, he has been left nearly bankrupt, putting the entire household under the control of his son Charles, who inherited an unrelated fortune. This, as you might imagine, has caused certain household tensions, and turned Charles in particular into a man constantly on the edge of losing his temper. To add to the problems, Charles has become engaged to the excruciatingly proper Miss Eugenia Wraxton, who feels it is her duty to help improve the moral tone and discipline of the household.

…He said stiffly: “Since you have brought up Miss Wraxton’s name, I shall be much obliged to you, cousin, if you will refrain from telling my sisters that she has a face like a horse!”

“But, Charles, no blame attaches to Miss Wraxton! She cannot help it, and that, I assure you, I have always pointed out to your sisters!”

“I consider Miss Wraxton’s countenance particularly well-bred!”

“Yes, indeed, but you have quite misunderstood the matter! I meant a particularly well-bred horse!”

“You meant, as I am perfectly aware, to belittle Miss Wraxton!”

“No, no! I am very fond of horses!” Sophy said earnestly.

His sister Cecelia, meanwhile, has ignored the love of the well-to-do and sensible Lord Charlbury for the love and adoration of a very bad poet, Mr. Augustus Fawnhope. The family, and especially Charles, deeply disapprove, not so much because of the poetry, but because Mr. Fawnhope has no money and no prospects whatsoever, and Cecelia, however romantic, does not seem particularly well suited for a life of poverty. His brother Herbert has run into some major financial troubles of his own. And to all this Sophy has added a monkey—an actual, rather rambunctious monkey not exactly good at calming things down.

Add in several other characters, including the fortune-hunter Sir Vincent Talgarth, an indolent Marquesa from Spain, various charming soldiers, and the now required cameo appearances from various historical characters (the Patronesses of Almack’s and various Royal Dukes), and you have, on the surface, one of Heyer’s frothiest romances—and one of her best and most tightly plotted endings. (Complete with little baby ducklings.) It’s laugh out loud hilarious, but beneath the surface, quite a lot is going on with gender relations and other issues.

Back to Sophy, for instance, who perhaps more than any other character, both defies and is constrained by gender roles. Unlike any other woman in the novel, she handles her own finances. Told that, as a woman, she cannot drive down a street patronized by aristocratic men, she instantly does so. And despite knowing that a woman of her class does not go to moneylenders, she does that as well.

But Sophy also admits that she cannot call out Sir Vincent because she is a woman—this only minutes after she has not hesitated to shoot someone else. And even Sophy, for all her ability to defy gender roles, does obey many of its strictures: she follows the advice of Sir Vincent Talgarth when assured that she cannot, as a woman, shop for her own horses; she displays cautious, ladylike and thus “correct” conduct at a company dinner; and in her final scenes, ensures that she is properly chaperoned at all times to prevent any scurrilous gossip. Each and every action of hers that goes against expected gender roles is described in negative terms: “Alarming,” “outrageous,” and “ruthless,” are just some of the terms leveled at her by other characters and the narrator.

Some of this may be deserved: Sophy can be actively cruel, and not just when she’s shooting someone. Her initial humiliating of Eugenia (by driving down Bond Street, something ladies are absolutely not supposed to do) may have been sparked by genuine anger, but as Sophy is correctly informed, it is also deeply cruel and distressing to Eugenia. (We’ll just hop over the many reasons why it shouldn’t have been cruel and distressing for Eugenia to be driven down a street—especially since she is only a passenger—since this is one aspect of gender relations that Heyer chooses to accept even in this novel that questions certain gender relations.)

For all that Eugenia functions as a semi-villain in the piece, a joyless figure determined to enforce propriety and ruin everyone’s fun, I find myself oddly sympathetic towards her. Perhaps Heyer felt the same; certainly Eugenia is the one woman in the end matched to a partner who will exactly suit her, and who she can live in comfort with. And speaking of Sophy shooting people, I can’t help but feel somewhat less sanguine than Sophy about Charlbury’s chances of a full recovery in this pre-antibiotic age. Sure, the wound works as a romantic gesture that binds Cecelia and Charlbury together, but what happens if the wound becomes infected?

But back to the gender relationships, something this novel takes a fairly sharp look at, not just with Sophy, but with others too. Lady Ombersley, for instance, is never told the full extent of her husband’s debts or the family’s financial troubles. The men agree that this is appropriate, but attentive readers can tell that the failure to tell Lady Ombersley and Cecelia the truth has added to the family stress. This is one reason why Sophy stresses that women have the ability to manipulate men, if they choose (Sophy most decidedly so chooses) and must not allow men to become domestic tyrants. But for all of Sophy’s insistence that men are easily manipulated, she is the only woman in the book (with the arguable exceptions of the Patronesses of Almack’s, in cameo roles, and the indolent marquesa) able to manipulate men. The other women find themselves under the control and management of men, legally and otherwise, despite the fact that some of these men probably shouldn’t be managing anything at all:

He had the greatest dread of being obliged to face unpleasantness, so he never allowed himself to think about unpleasant things, which answered very well, and could be supported in times of really inescapable stress by his genius for persuading himself that any disagreeable necessity forced upon him by his own folly, or his son’s overriding will, was the outcome of his own choice and wise decision.

(I just like that quote. Moving on.)

The Grand Sophy also reiterates Heyer’s point that the best marriages focus on practicality and kindness, not romance: Charlbury is not the best sort of suitor because of his wealth and respectability, but because he is the sort of man who can find umbrellas in the rain. At the same time, Heyer recognizes that Cecelia, at least, needs some of the romantic trappings: she’s unable to speak her true feelings (despite a lot of sniffling and hints in that direction) until Charlbury is shot. The only “romantic” pairing is that of Cecilia and her poet, and it doesn’t go well. Charles and Sophy fall in love because—well, that’s not entirely clear, but Sophy seems to respect Charles’ focus on his family and the respect he has gained from his friends, and Charles realizes Sophy’s genuine kindness when he sees her nursing his younger sister.

This distaste for romance is quite possibly why Heyer presents us with not one, not two, but three unconvincing couples. (She was probably also still reacting to fears that novels focusing on romance would never be taken seriously by male critics—not that her novels of this period were taken seriously by anyone other than fans and booksellers.) Indeed, the only two that feel at all suited for each other are not even officially together by the end of the book (though quite obviously headed in that direction.) Even the passionate kiss between Sophy and Charles is sorta quashed with the phrase “I dislike you excessively” which does seem to sum things up. Still.

Anyway. I’m stalling a bit, because I’m not happy about having to talk about the next bit, the most problematic element of the book, the one that (along with the manipulative heroine) can make it uncomfortable for most readers: the scene where Sophy confronts the Jewish moneylender, Mr. Goldhanger.

Brief aside: most editions have edited out the more objectionable phrases in this scene. The current ebook available from Sourcebooks put the words right back in, including the bit about Mr. Goldhanger’s “Semitic nose,” and greasy hair, as well as Herbert’s comment that his brother Charles is as tightfisted as a Jew, things I missed in my original reading because they weren’t in my original reading. Which means that anyone saying, “But that’s not in the book—” It might not be in your copy. But the bits I’m discussing were certainly in the original text and are still in some of the editions available today.

In any case, even without those references, Mr. Goldhanger, a moneylender who has illegally lent money to Charles’ younger brother Herbert at outrageous rates of interest, is every negative stereotype of a Jewish character. He is easily bested by the younger Sophy. It’s a moment that I could take as a wonderful bit of a woman triumphing over a man—if not for the stereotypical, anti-Jewish statements. In a book written and published in 1950.

World War II did not magically eliminate racism and stereotyping from British culture, and Heyer was not of course alone in British literature in penning stereotypical descriptions of Jews. What makes her slightly unusual here, however, is that she was still penning this after World War II, when her other peers (notably Agatha Christie) were backing off from such stereotypes of at least Jewish characters. And if Heyer’s brief sojourn in Africa had not precisely turned her into an advocate for civil rights, or indeed inspired her to think about racial relations at all, she had never formed part of a blatantly racist sect. Nor is the scene without historical basis: multiple aristocrats of the Regency period did turn to moneylenders—some of whom, but not all, were Jewish—when they found themselves burdened with heavy debt. The moneylenders could and did charge crushing levels of interest, trapping their clients in a cycle of debt; in that, Heyer is accurate.

Nonetheless, the entire scene makes for uncomfortable reading for me. Worse, I think, Mr. Goldhanger represents a step backwards for Heyer. She had previously featured a Jewish character in The Unfinished Clue, but although that character displays numerous Jewish stereotypes, he is also shown as practical, kindly and of definite assistance. She also had a Jewish character in The Blunt Instrument, but although this character is definitely depicted negatively, he is also seen through the eyes of two police shown to have multiple biases; the stereotypes here are theirs. That character is also a possible murderer with reasons to distrust the police (and vice versa), so a certain negativity can be expected. In The Grand Sophy, the stereotypes—and they are much more negative than those in the previous books—belong both to the narrator and to Goldhanger himself.

It’s a pity because, without this scene, I could easily rank The Grand Sophy as Heyer’s very best (if not quite my all time favorite.) Certainly, she was rarely to surpass the perfectly timed comedy of the book’s final scenes, with its little ducklings and distracted cooks and makeshift butlers, and the book has other scenes that still make me laugh out loud, no matter how many times I’ve read them. And yet that laughter now has an uneasy tinge to it

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.