Charlie Brown looked into the shining void that is Christmas, and became a hero.

Here was a child who acknowledged the sadness beneath the festivity, the loneliness, the aching search for meaning under tinsel. This half hour met the challenge thrown down by Rudolph, raised the bar for the Grinch, and created the template that has been used by nearly every animated special, sitcom, and even drama since the 1960s. Charlie Brown dispensed with all merriment, demanded to know the meaning of Christmas, and got a perfect answer.

Here’s the entire plot of A Charlie Brown Christmas: Charlie Brown is sad, so Lucy asks him to direct the Christmas pageant. He decides to buy a tree to put on the stage. He buys a tree the kids don’t like, so he is EVEN MORE SAD. They decorate the tree and make up with him. But hung upon that simple, spindly tree of a premise are meditations on faith, loss, the role of emotional truth in a capitalist system, and whether snowflakes are better in January than December.

Eastern Syndicates, You Say?

I’ll just pop in here like a jerk and get this over with: the only reason this classic of anti-commercialism even exists is that Coca-Cola wanted a 26-minute long program to showcase advertisements for its delicious bubbly sugar water. OK, enough of that, apologies, on with the special.

The Tree

The central plot of A Charlie Brown Christmas was inspired by producer Lee Mendelson, who told Schulz that he and his wife had celebrated a recent Christmas by reading Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Fir Tree” to their children. Schulz spun that into a tale of two trees, hitting upon an impossibly neat symbol of commercialized: aluminum Christmas at war with good ol’ classic evergreen.

I ask you to look at the above picture, however, and imagine yourself in 1965. If you were actually going to buy an aluminum Christmas tree, you were probably buying an Evergleam from Aluminum Specialties in Manitowoc, Wisconsin. You were going to get it at a department store or order it from the Sears catalogue, not at a tree farm—the whole point was that it came in a box and was easy to assemble right there in your stylish mod home! So including an actual fake tree farm is freaking brilliant satire, which unfortunately backfired on me.

I mean, again, look at these aluminum Christmas trees:

LOOK AT THEM:

Don’t you want one of those trees? I want ALL of those trees. (And I mean, sure, I want the little scrappy one too, but maybe to plant in the backyard, not display inside my house.) I used to pause my tape of this special and just sit there agog, trying to pick which tree was the prettiest. To give you an idea, here’s my current tree:

Isn’t she a beaut? And my greatest wish is that one day I’ll live somewhere with enough space to have two trees, so I can have a white one with red decorations, like the one behind Lucille Ball as she leads a choir in “The 12 Days of Christmas”. This appeared on The Lucy Show episode that aired four days after A Charlie Brown Christmas. But the giant white tree of my dreams might be hard to come by, because within two years of the special’s premiere, sales of aluminum Christmas trees had dropped precipitously, and the fad was pretty much over by 1969. And all because Charlie wants a real, Germanic evergreen, not an Evergleam.

His tree came to symbolize something authentic and beautiful, a unique soul in the midst of candy-colored dross—which is why you can buy a plastic version of it from Amazon. Hey, here’s one that comes with Linus’ blanket already wrapped around it! You don’t even have to provide the love.

Jingle Bells, Beethoven, All That Jazz

Schulz hated jazz, but wisely acquiesced to everyone else’s love of Vince Guaraldi, which is why so many of us have a classic, Quadruple Platinum, nigh-perfect jazz Christmas album to soundtrack our holiday parties so they walk that perfect knife’s edge between irony and sincerity.

Wait, that’s not just me, is it?

You know exactly what you’re in for when “Christmastime Is Here” starts up. Have the words “Happiness and cheer” ever sounded more mournful? What was this like, for the generation of kids who watched this special on tiny screens encased in giant wooden cabinets, sitting in front of their shiny aluminum Christmas trees? Were there kids out there who felt like someone finally got it? Someone else understood the feeling of hollowness that overwhelmed them sometimes when they looked at their families, happily ripping presents open?

Lucy is Actually a Decent Therapist?

How insightful is it for Lucy to figure out that Charlie Brown’s problems are rooted in fear? And for all that she wants nickels and real estate, she actually diagnoses Charlie perfectly. Her idea to give him more involvement isn’t just a great form of therapy, it’s also surprisingly altruistic, since she’s the one who faces the other kids’ wrath when they find out about their new director. Seriously, she’s already doing better than the therapist I (briefly) consulted.

All I Want For Christmas Is My Fair Share

As in the Halloween special, Sally Brown is my damn hero. She believes in Santa, she’s excited to be in the play, and she’s happy to accept her gifts in the form of $10s and $20s.

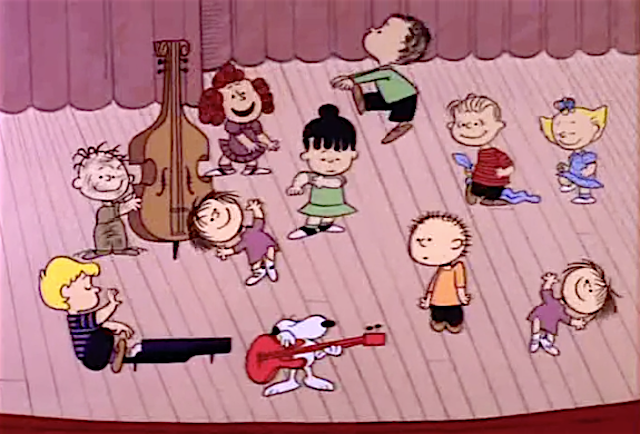

What the Heck was Their Play Even Supposed to Be?

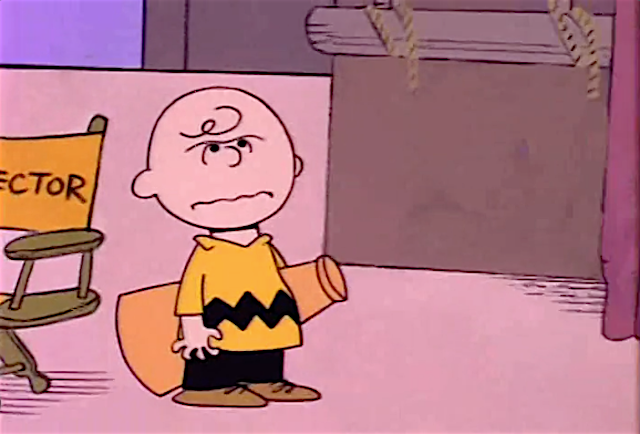

There’s an innkeeper and an innkeeper’s wife. And a shepherd, who also has a wife. A dog is playing all the animals. There’s also a Christmas Queen. And Schroeder playing mood music on the side of the stage. At a certain point half the kids from the dance sequence disappear, and then come back in the end to sing. Wasn’t this just supposed to be a Nativity play? Was Linus actually supposed to recite the entire passage from Luke? How is a “Christmas Queen” going to interact with the solemnity of a Nativity story? Isn’t Snoopy going to break the illusion a little? This whole concept seems very unwieldy.

No wonder Charlie Brown seethes with rage.

Charles Schulz’ Old-Time Gospel Hour

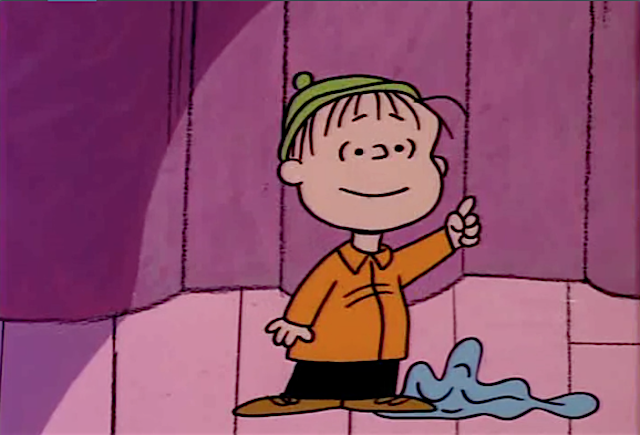

According to all accounts of the making of the special, there were two areas where Schulz dug in his heels. First, when producer Lee Mendelson mentioned putting a laugh track on the special, he literally got up and walked out of the room. It wasn’t brought up after that. Second, Schulz came in with an entire gospel passage for Linus to recite. Mendelsohn and director Bill Melendez were both hesitant to include so much, and according to some versions of the story, the CBS execs were also freaked out by it.

Religion wasn’t brought up too much on US television in the ’50s and ’60s. People were trying to adhere to the bland idea of equality between Catholics, Protestants, and Jews, who were all good suburban monotheists but too polite to talk about it in public. But Schulz, who was increasingly concerned that “Christianity” was being merged with “Americanism” in the popular imagination, also felt that if your main character spends the whole special asking about the true meaning of Christmas, having the other characters say “presents and freshly-bottled Coca-Cola, probably” was a bit disingenuous.

There were other depictions of religion on TV, certainly: Amahl and The Night Visitors, an opera about the Three Kings going on a sidequest to help a handicapped boy, was shown annually from 1951–1966. In 1952, Westinghouse One produced The Nativity, a mystery play which you can watch here. In 1953 Bell Telephone sponsored The Spirit of Christmas, a marionette show that paired “A Visit from St. Nicholas” with The Nativity. These were all serious adaptations, however, family friendly but not meant specifically for children. There were also plenty of adaptations of A Christmas Carol and The Nutcracker, which certainly have magical elements, but avoid mentioning the religious aspect of the Christmas season. And obviously 1964’s Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer is a Santa story.

A Charlie Brown Christmas does something completely different by mixing comedy and melancholy throughout. It gives us a realistic and modern mid-’60s version of Christmas. There is no miracle, no toys come to life, no visit from Santa. (Come to think of it, only Sally expresses a belief in Santa.) But alongside that is a dedication to holding onto the religious aspect of the holiday—not the dramatic story of mystical kings filing in with gifts, or of a refugee family running from the wrath of Herod, but rather the basic idea of goodwill toward men.

Only the Gospel of Luke includes the passage that we think of as The Nativity. Mark begins with the adult Jesus’ baptism by John the Baptist. Matthew begins before Jesus’ birth by outlining Joseph’s genealogy, and then shows us The Three Wise Men, Herod’s Massacre of the Innocents and the Holy Family’s Flight into Egypt. John, the most philosophical of the Gospels, begins literally at the beginning of time itself (In the beginning was the Word, etc.) before skipping ahead to relate John the Baptist’s ministry, and only then introduces Jesus onto the scene. Most pop culture interpretations (not to mention Nativity scenes) combine parts of Matthew and Luke to give us a kid-friendly melange of angels, shepherds, the Innkeeper, the Three Magi/Kings/Wisemen, animals, and a Star that ensures everyone arrives at the right manger, rather than accidentally worshiping Brian down the street. The two Gospels are blended together with no indication that they are different version of the story, written by different people in (probably) different decades.

This makes Charlie Brown’s choice to use the Gospel of Luke all the more striking: not only does it hit the audience with unvarnished religion, but it sticks strictly to its source material. This centers the show on the image of a desperately poor family surrounded by equally subsistence-level shepherds, all being spoken to directly by angels without the mediation of Persian mystics. This miracle doesn’t happen with any sort of royal sanction, or even royal awareness, because Herod doesn’t care enough to massacre anyone in this version. No one “important” witnesses the miracle, just as no adult authorities come into the auditorium to be impressed with Linus’ re-telling of the story. This is a story about peasants being told by children, and as the peasants turn out to be profoundly important, so too the children in Peanuts are revealed to contain wells of emotion and even wisdom.

Personally? I think it’s fantastic, and I think the idea that a special about Christmas should have the Christianity edited out of it is ridiculous. But I can only be happy with it because we also have the Santa-based Christmas of Rudolph and the vague “Christmas-feeling” Christmas of the Grinch to serve as complements. I’d be a lot happier still if there were classic specials that celebrated Rosh Hashanah, Eid al-Fitr, Vesākha, and all the other holidays that are important to millions of Americans.

In Which I Get Realism for Christmas

Charlie Brown doesn’t shy away from religion, but here’s the thing: this is a starkly, unrelentingly realistic special. I watch a lot of Christmas specials, movies, and episodes each year. Even the ones meant for adults (e.g. It’s A Wonderful Life, The Bishop’s Wife, MacGyver, Walker: Texas Ranger) feature angels as characters and incidents that can only be explained as supernatural. Sitcoms have spent decades roasting the “Santa is real” chestnut. Even the holiday horror movies chuck reality out the be-garlanded window! In Santa’s Slay, Santa himself is revealed to be a centuries-old demon who rides through the night in a sleigh pulled by a red-nosed “Hell-Deer”, and both Rare Exports and Krampus feature Austria’s favorite Christmas demon wreaking paranormal havoc. It’s rare that you get a special that doesn’t have some element of real magic in it.

But Charlie Brown, all the way back in 1966, nailed it. Charlie is searching for the true meaning of Christmas, and Linus relates the Gospel. But God doesn’t come swooping in to help Charlie. Neither does Santa, or an elf, or a reindeer, or a Nutcracker Prince, or the Ghost of Christmas 1965. Think about all the other Christmas specials from this era: Mr. Magoo is in the world of A Christmas Carol. Rudolph and Frosty both live in magical realms where Santa exists, and the Grinch lives in a fantasy land where his heart can grow and give him extra strength because LOVE. Charlie Brown, unique among animated Christmas heroes, lives in our world.

The other kids are greedy, bloodthirsty, and mean. When Charlie brings his tree back, the insults they fling—”Boy, are you stupid Charlie Brown”; “I told you he’d goof it up. He isn’t the kind you can depend on to do anything right”; “You’re hopeless, Charlie Brown”; “You’ve been dumb before, Charlie Brown, but this time, you really did it”—go beyond teasing into actual abuse. There is no outside authority to defend him, and he himself has no defense, since he bought the tree on a purely emotional impulse. Linus stands up and recites his speech, sure, but I didn’t see Linus rushing to his defense when the other kids circled like hyenas scenting prey. When Charlie takes his tree and walks out into the snow, he goes alone. He takes comfort in millennia-old words, believes in them, and is promptly rewarded by his tree’s death.

His response? “Oh! Everything I touch gets ruined.”

This has become something of a stock phrase of mine, something I say as a gag when I drop things, put too much sugar in my coffee, find a typo in an article… but I encourage you to go hang out in that quote for a minute. Sit with it. Think about the kind of person who one moment is serene and filled with faith, and the next collapses so utterly that they would say that sentence. Think about the fact that this moment comes after the big moment with Linus under the spotlight. Think about Charlie, alone in the dark again, saying this to the tree he thinks he’s killed, while all the other kids are warm in the theater, meditating on Linus’ grand performance.

Here, in the heart of our greatest Christmas special, Charles Schulz doesn’t pretend that the joy of an epiphany will last forever. Linus’ quote doesn’t save Charlie from the pain he feels. What saves him, eventually, is the other kids coming out into the cold with him and rescuing his tree. They put their own prejudices aside and work together to bring the “commercialism” of Snoopy decorations and the “classic Christmas” of Charlie’s tree together, creating a synthesis of Christmases that heals both the tree and their community. They do this as a gift to Charlie, inviting him into a holiday that allows for Christmas Queens, Beethoven Christmas music, fake plastic trees, real, needy trees, bright blinking lights, and cold, silent nights. It’s also, implicitly, a plea for forgiveness. Which of course he grants, and then the children sing together in a spirit of harmony and peace.

And that’s what Christmas is all about, Charlie Brown.

Originally published in December 2015 for the special’s 50th Anniversary.