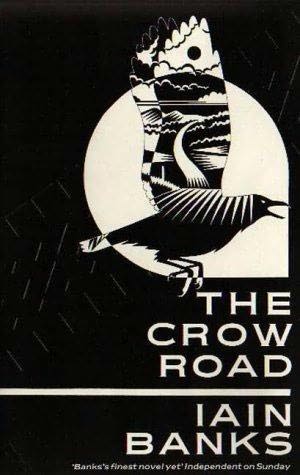

I bought this particular copy of The Crow Road in Hay-on-Wye. Abacus had done nifty patching b-format paperbacks of all Banks’s novels, all with metaphorical covers, the mainstream books in black and white and the SF coloured. (I’m sure they were thinking something when they made that decision, but it’s too obvious to be interesting.) Emmet had all the other ones in matching editions, but had lost his Crow Road, and meanwhile they’d come out with new ugly covers. So I was in Hay-on-Wye, town of books, and I was writing Tooth and Claw and reading Trollope. In one of the second hand bookshops there I bought fifteen Trollope novels and The Crow Road. The shop assistant looked at me oddly. “That’s a bit different!” she said.

“Well,” I said, “I suppose it is a bit different in that it’s set in 1990 rather than 1880, but they’re all books with a strong sense of place and time and family, where the boy gets the girl in the end and the family secrets are unravelled. I’ll grant you the Banks has a bit more sex.”

This somehow didn’t stop her looking at me oddly I think there may be a lot of people out there whose reading tastes are incredibly narrow.

My main question on re-reading The Crow Road now is to ask why people don’t write SF like this. SF stories that are about people but informed with the history that is going on around them. More specifically, why is it that Iain Banks writes these mainstream books with great characters and voice and a strong sense of place and then writes SF with nifty backgrounds and ideas but almost lacking in characters? The only one of his SF novels that has characters I remember is Use of Weapons. There are lots of writers who write SF and mainstream, but Banks is the only one whose mainstream I like better. Mystifying.

The Crow Road famously begins:

It was the day my grandmother exploded. I sat in the crematorium, listening to my Uncle Hamish quietly snoring in harmony to Bach’s Mass in B minor, and I reflected that it always seemed to be death that drew me back to Gallanach.

“The crow road” means death, and “he’s away the crow road” means that someone has died. The book begins with a funeral, and there are several more, along with a sprinkling of weddings and christenings, before the end. It’s also the title of a work of fiction Rory’s working on at the time of his death. Rory is Prentice’s other uncle, and Prentice is the first person narrator of a large proportion of the novel. This is a family saga, and if you can’t cope with a couple of generations of McHoans and Urvills and Watts, you won’t like it. I’d also advise against it if you loathe Scotland, as all the characters are Scottish and the whole novel takes place in Scotland. Oh, and they drink like they have no care for their livers. But if you don’t mind these little things, it’s a very good read.

The present tense of the story is set very precisely in 1989 and ’90—coincidentally, the exact same time as Atwood’s The Robber Bride, which I read last week. The First Gulf War is mentioned in both books. One of the characters in The Crow Road goes to Canada, but when I wonder if she’ll encounter the characters from The Robber Bride, my brain explodes. Toronto and Gallanach—or maybe just Atwood and Banks—are clearly on different planets. And yet there are similarities. Both books have a present and long flashbacks into the past—The Crow Road goes back to Prentice’s father’s childhood. Still, different planets. Different assumptions about how human beings are.

So, why do you want to read The Crow Road? It’s absorbing. It’s very funny, with humour arising from situation and characters. (There’s an atheist struck by lightning climbing a church.) There’s a family like my family, which isn’t to say realistic. There are the sort of situations you have in real life but so rarely in fiction, like the bit where the two young men are digging their father’s grave while the gravedigger sleeps, and they wake him up by laughing, and he’s appalled. There’s a mysterious disappearance that might be murder. There’s True Love, false love, skullduggery, death, birth, sex, cars, and Scotland.

The land around Gallanach is thick with ancient monuments; burial sites, henges, and strangeky carved rocks. You can hardly put a foot down without stepping on somethin that had religious significance to somebody sometime. Verity had heard of all this ancient stoneware but she’d never really seen it properly, her visits to Gallanach in the past had been busyt with other things, and about the only thing she had seen was Dunadd, because it was an eays walk from the castle. And of course, because we’d lived hereall our lives, none of the rest of us had bothered to visit half the places either.

It isn’t in any way a genre novel, but it’s great fun and so very good.