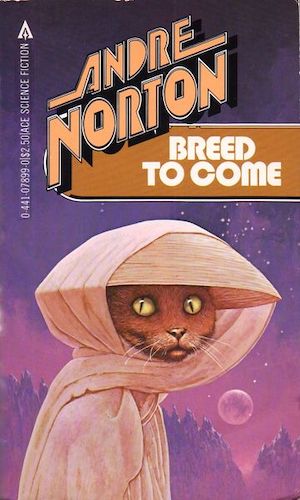

Breed to Come is one of Norton’s better-loved books. It was published in the early Seventies, shortly before what is effectively a companion volume (and was packaged so in Baen Books’ ebook revival of Norton’s works), Iron Cage. Whereas Iron Cage frames itself as a human variation on a cat locked in a cage and dumped out of a car, with aliens as the villains who cage the humans, Breed to Come tells the story of an Earth abandoned by humans and inhabited by intelligent animals.

The primary protagonist is Furtig, a mutated cat who lives in a colony related to a famous explorer and leader, Gammage. The People, as they call themselves, have evolved somewhat functional hands—at the cost of their ancestral claws—and the ability to walk upright as well as on all fours. They coexist more or less peacefully with mutated pigs, have an adversarial relationship with local tribes of mutated dogs, and open enmity with the mutated rats who infest the ruined cities of the Demons.

The Demons, it quickly becomes clear, were humans. They are long gone. Some went into space. Those who remained on Earth either killed one another off or died of the same disease that caused some of their livestock, lab animals, and pets to develop enhanced intelligence.

Gammage may or not be still alive when the story begins. Furtig is an intrepid hunter and explorer himself, with mental abilities that he does not at first realize are exceptional. He is not otherwise remarkable by his people’s standards, and is not terribly surprised when he fails to win a mate in a ritual trial by combat. He has already decided to seek out Gammage, if he still lives, and join his effort to raise the People’s profile in the world.

This in fact Furtig manages to do, after a series of fairly standard Norton adventures: battles with the evil Rattons, encounters with the Barkers and the Tuskers, and lengthy subterranean expeditions. He not only finds Gammage but one of his own close relatives who had been missing and presumed dead, and a colony of further mutated cats, some of whom have even lost most of their fur, but who have evolved fully functional hands.

Gammage has a mission, not only to master Demon technology but to use it against the Demons themselves. He believes that the ones who escaped into space are coming back in response to the beacon that they left behind, and he wants to be ready for them. He is convinced that this will happen soon.

Buy the Book

Sun-Daughters, Sea-Daughters

Furtig is not sure he believes in that, but he is on board with the appropriation of technology. This does not mean that he fits easily or well into Gammage’s colony. The “In-born” seem aloof and arrogant to him, and most of them command knowledge that he lacks, as well as possessing much more facile fingers.

His situation improves considerably when it becomes apparent that he has psychic abilities. He can track other People with his mind, and see distant places by focusing his mind on them. This is tremendously important for scouts who are trying to retrieve Demon records from areas taken over by the Rattons.

Three-quarters of the way through the story, everything changes. It’s been thoroughly foreshadowed and clearly set up, but it’s still a bit startling to suddenly get, in italics, the viewpoint of the secondary protagonist, Ayana, a human woman on a spaceship headed for Earth. There are four in the crew, two men and two women, and she is the medic.

Ayana is fundamentally a decent person. Her culture is not. It’s clearly totalitarian, it scores and assesses people and assigns them jobs and mates without choice or appeal, and if a person doesn’t fit the mold, she’s mentally altered until she does. The male Ayana has been bound to is, to put it bluntly, a macho asshole, and her role is to tone him down and keep him in line as much as possible.

The four scouts have been sent to reconnoiter the planet their ancestors abandoned half a millennium before, to discover whether it can be re-colonized. Humans are close to destroying the world they fled to, in much the same way they destroyed Earth. Now they need a new planet to poison.

One of the first things Ayana’s mate Tan does after they land is capture a pair of young Tuskers from their mother—and cook and eat them. Ayana has an awful feeling about that, and warns the others that maybe these aren’t just food, but Tan mocks her and the other two pay no attention. Tan also, while exploring, catches video of Furtig and another one of the People escaping, injured, from a Ratton attack, but they don’t realize for some time what or who they’re seeing. Ayana has an inkling, but again, can’t convince the others.

All too quickly, the invaders and the natives clash. Tan allies with the Rattons and captures and tortures some of the People. Ayana goes rogue, discovers that she was right—these “animals” are highly intelligent—and joins forces with them to overcome Tan and the evil, wicked, disgusting Rattons.

It’s clear by then that something in the air of Earth corrupts human minds. They lose their ability to think rationally, and they become aggressive and destructive. It’s worst for Tan, but the others are affected as well.

Ayana takes control of the scout force, overcomes Tan, and blasts off to her home world. Humans will not come back, she promises the People. This world is as toxic to them as they are to it.

All in all this is quite a dark book. As engaging as the People are, and as laudable as Gammage is in his efforts to raise their technological level and unify the different species (but not the evil, disgusting Rattons–why, yes, that bothered me; I dislike this kind of reflexive demonization), the basis of the worldbuilding is the complete depravity of the human species. All they ever do is smash and ruin and destroy. They use and abuse other species, treat them abominably, cage and torture them, and kill and eat sentient beings without stopping to ask if they might, in fact, be sentient.

There are, it’s true, some who aren’t all bad, who try to do the right thing. They don’t make up for the overall awfulness of their species, and the world as a whole is better off without them. Better to leave it to the animals, who aren’t totally pure or perfect either, but who (except for the evil disgusting Rattons) are generally good and reasonable people.

Right about now, I have to admit, this looks more accurate than not. The human species has been working exceptionally hard of late to trash the planet and itself.

And yet, though this is a favorite with some of our regular commenters, I find I like other Norton novels and universes better. It’s not her worst by any means, but for me it’s not a favorite. It reminds me strongly of her collaborative Star Ka’at series for younger readers. These were published in the same decade, as if these particular themes preoccupied her to the extent of writing and rewriting them several times over.

She did have a strong apocalyptic streak, and frequently wrote about the destruction and abandonment of Earth. What’s different here is the fact that humans are completely unredeemable. There’s no possibility of saving them or of restoring them to their native planet. Wherever they go, they destroy their environment and eventually themselves.

Nor are they, as a species, capable of treating other life forms as partners, let alone equals. Ayana does collaborate with the People and their allies, but that’s a kind of atonement for what her ancestors did to them before abandoning the ruined planet. She does not stay, and she undertakes to prevent humans from ever coming back to use and brutalize the new rulers of Earth.

That’s not to say everything is awful on this altered planet. Norton takes great care to depict the People as cats. They don’t think or act like humans. They’re their own thing, clearly based on their original species. Their social structure and their gender divisions suggest what was known at the time of cat behavior.

She has great female characters, too. Although her main protagonist is male, he has multiple female friends, teachers, and allies. Ayana is as complex a character as Norton was able to portray, with a real moral dilemma and a profound and painful epiphany as she learns the truth of what humans did to Earth and its animals.

Still, in my personal lineup of Norton novels, I find I lean more toward the Star Ka’at version of the complicated relationship between humans and cats. Norton did human-animal companionship so well. I miss it here.

Next time I’ll be switching genres again, with the portal fantasy Here Abide Monsters.

Judith Tarr’s first novel, The Isle of Glass, appeared in 1985. Since then she’s written novels and shorter works of historical fiction and historical fantasy and epic fantasy and space opera and contemporary fantasy, many of which have been reborn as ebooks. She has even written a primer for writers: Writing Horses: The Fine Art of Getting It Right. She has won the Crawford Award, and been a finalist for the World Fantasy Award and the Locus Award. She lives in Arizona with an assortment of cats, a blue-eyed dog, and a herd of Lipizzan horses.