In one of those happy coincidences that often befall the writer-by-trade, while I was pondering the nature of the racehorse and the psychology of the stallion, I happened across a review of a new book that looked as if it would focus on both themes. Geraldine Brooks’ Horse is the work of a famously meticulous researcher who is also a devoted horse person. And it shows.

I did not know anything about the author when I read the book, except that this is far from her first novel, and she’s won a Pulitzer Prize. Therefore I expected some of what I got: highly polished prose, visibly topical characters and themes, and a familiar device of literary novels, the interweaving of a carefully described past with a present that explicitly reflects it.

What I also got was an engrossing read, with twists and turns that left me breathless. Wild coincidences and bizarre connections that actually, historically happened. And a deep, true knowledge of and love for horses.

The core of the story is the most famous Thoroughbred sire of the nineteenth century, one of the great stars of the racetrack, the bay stallion Lexington. Lexington’s story is inextricably bound up with the history of race in the United States, and with the American Civil War. He was born and bred in Kentucky, part-owned by a free Black horse trainer, sold out from under that trainer (because of a rule on the track that no Black man could own a racehorse) to a speculator in New Orleans, and eventually sent back up north to stand at stud. He died at the quite decent age of twenty-five, having sired hundreds of offspring, including whole generations of racing stars and, for more general historical interest, General Grant’s favorite warhorse, Cincinnati.

Lexington himself did not race much, though he won spectacularly when he did, over distances that would break a modern Thoroughbred—four miles at a time, in multiple heats on the same day. He went blind and his owner went overseas to try to make himself even richer racing American horses on English tracks. Lexington’s life was much longer and happier, and much easier, as a famous and spectacularly lucrative breeding stallion.

Buy the Book

Horse

The owner blew through a fortune and died penniless. Lexington died in the fullness of his age, but was not allowed to rest in peace. He was exhumed six months after death, and his skeleton was wired together and put on display, along with portraits painted during his life by the top equine artists of the day.

All of that would be enough to make a legend, but what happened to the skeleton and one of the portraits is an even wilder tale. The skeleton ended up in an attic at the Smithsonian, simply labeled, Horse. It was rediscovered in 2010, identified as not just a random equine but a great star of the past, and ended up on display again at last in the Museum of the Horse at the Kentucky Horse Park. Back full circle, and back to stardom again.

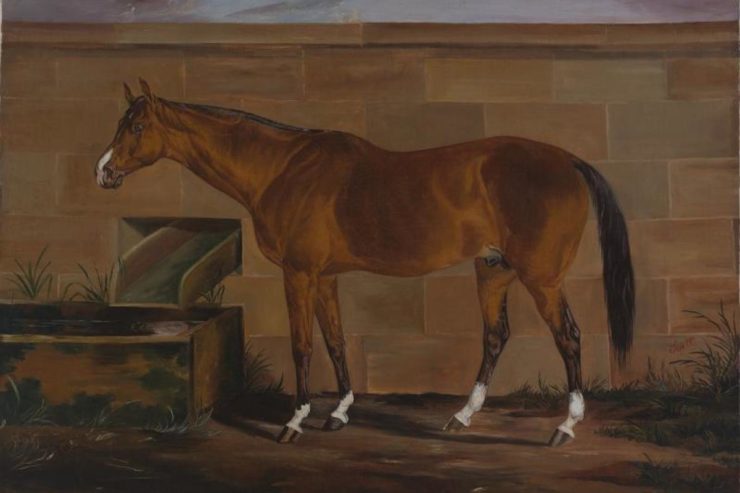

Meanwhile his most famous portrait, by artist Thomas Scott, showed up in the estate of art dealer Martha Jackson. Jackson was one of the premier dealers of abstract art—Jackson Pollock was one of her regular clients—but in among all the ultramodern works was this one complete outlier: a nineteenth-century horse painting. Nobody knows how or why it got there, but there it was. And now it shares space in Kentucky with the skeleton of the horse it represents.

Brooks fictionalizes the timeline of the discovery, moving it from 2010 to 2019, in order to heighten the racial tension that runs through the narrative. She adds a character who is known only as the title to a lost painting, the groom Jarret; she fleshes out the barely-extant bones of his story and ties it in with the history of the trainer, Harry Lewis, who lost Lexington to the injustice of racist laws. She adds a pair of fictional characters to her modern timeline, the Australian osteologist, Jess, and the young African-American art historian, Theo.

All of them are horse people in one way or another. Jess doesn’t consider herself such, but she’s utterly fascinated by the skeleton of the initially anonymous horse, both as an anatomical structure and as an artifact of nineteenth-century skeletal reconstruction. Theo is a horseman, a star polo player driven out of the game by relentless racism. The nineteenth-century characters reflect the tension between the modern characters and their culture and their period: the free Black man Harry Lewis, his enslaved son Jarret whom he cannot afford to buy free, the infamous abolitionists’ daughter and granddaughter Mary Barr Clay. And, in the middle and a little bit of a non sequitur, the artist turned gallery owner Martha Jackson, whose mother, a famous equestrienne, died in a riding accident.

Lewis is a racehorse trainer, and he oversees the breeding of the blind, vicious, and very, very fast racehorse Boston to a closely related and frankly vicious but very, very fast mare. The result, named Darley at birth, is a bright bay colt with four white socks, whom Lewis co-owns with the owner of his birth farm. In the novel, Jarret, then a young boy, is present at the colt’s birth, and bonds deeply with him.

Jarret’s story as Brooks tells it is a love story between a horse and his human. From the moment of the colt’s birth, as much as time, fate, and racial injustice will allow, Jarret and the horse who came to be known as Lexington are inseparable. They’re soulmates. They are far more in sync with each other than any of the humans in the book, even humans who are lovers. Maybe especially those.

It takes a horse person to do this right, and there is no question that Brooks is a horse person. She knows how horses work, both physically and mentally. She understands horse racing, both the power and passion and the terrible prices it exacts. Above all, she understands the bond between the species, the ways in which the large, fast, strong herd and prey animal connects with the apex predator.

She builds all of this into the story of Jarret and Lexington. Everyone else in the book is a user of horses. A painter who is produces ads for sellers and breeders in an age of scarce or nonexistent access to photography. A breeder, a racehorse owner, a polo player, for whom the horses are sports equipment. A scientist who sees a horse as a structure of bones and ligaments. Even a horse girl who rides her horses into a lather as a way of expressing her frustrations with the constraints of her culture and class, and dumps them on grooms who have no more power over their own lives than the horses do.

The only one who sees the horse as a fellow being, who really and truly understands him, is the enslaved groom. After emancipation, Jarret stays with the horse who belongs more truly to him (and he to the horse) than any White man who may have claimed to own either of them. It’s a powerful story, and it touches the heart of both meanings of the word race.

I read this book on multiple levels. For SFF Equines, I found it to be a master class in writing horses. Brooks absolutely knows her stuff. Her facts are solid and her understanding of horses is deep and broad. It’s well worth reading for that, even without the rest.

Judith Tarr is a lifelong horse person. She supports her habit by writing works of fantasy and science fiction as well as historical novels, many of which have been published as ebooks. She’s written a primer for writers who want to write about horses: Writing Horses: The Fine Art of Getting It Right. She lives near Tucson, Arizona with a herd of Lipizzans, a clowder of cats, and a blue-eyed dog.