In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

Jerry Pournelle’s A Spaceship for the King is one his earliest works, and has everything I look for when selecting fiction to highlight in this column; gripping portrayals of combat on both land and sea, political intrigue, and scientists working against impossible deadlines. When I heard that Pournelle had passed away in his sleep on 8 September 2017, I decided that a review of this book would be a good way to pay tribute to his life, his work, and his contribution to the field of science fiction.

A Spaceship for the King takes place in the time of the Second Empire of Man, when a fanatical effort is being made to consolidate every inhabited planet into the Empire and prevent the disunity and carnage that destroyed the First Empire. Not all of the planets being forced into the Imperial fold are treated equally, however. On the planet known as Prince Samual’s World, the government prepares a desperate plan to negotiate the best possible terms for joining the Empire. This plan involves sending Colonel Nathan MacKinnie on a “trade” mission to a less developed world, where there is reportedly a lost library of highly technical information that could determine the fate of his home planet.

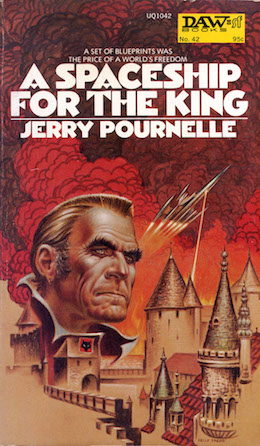

The book first appeared in three installments in Analog, in December 1971, January 1972, and February 1972. This was Pournelle’s second appearance in Analog under his own name, the first being “Peace with Honor,” a tale of Colonel Falkenberg’s Legion, published in Analog in May of 1971. That tale was eventually included in the book The Mercenary, which I reviewed here. A Spaceship for the King then appeared in book form as a DAW SF edition in February 1973, with one of those beautiful covers that Kelly Freas was doing for DAW back in those days. An expanded version of the book, published in 1981 and retitled King David’s Spaceship, included substantial rewrites and a large amount of additional material that carried the story past the original ending.

About the Author

Jerry Pournelle (1933-2017) had a considerable impact on the field of science fiction over the course of his career. He could be a polarizing figure, but whether you agreed or disagreed with him, it was impossible to ignore him. Editor John Campbell of Analog, at the end of a long career of grooming the greatest of science fiction authors, discovered Pournelle, who soon became a regular contributor to the magazine.

Before he became a science fiction writer, Pournelle had a long and varied career. He served as an Army officer during the Korean War. He worked in the aerospace industry on defense projects. He assisted a candidate running for mayor of Los Angeles. He co-wrote, with frequent collaborator Stefan Possony, a noted book on military strategy, The Strategy of Technology, which was used at several military academies and war colleges. He used all of this experience to great advantage in his fiction, creating accurate portrayals of technology, of warfare, of political machinations, and constructing characters that felt like real people.

Alongside his fiction writing career, Pournelle was a columnist for Byte magazine, a pioneer in reviewing software from the perspective of the end user. His Chaos Manor website is often cited as one of the first examples of what we now know as “blogs.” And Pournelle is reputed to be one of the first SF authors to use a word processor instead of a typewriter. Pournelle also wrote SF-related non-fiction, with his “A Step Further Out” column appearing in Galaxy, and his “Alternate View” columns in Analog.

While Pournelle wrote many works on his own, he also frequently collaborated with other authors. His CoDominium/Empire of Man future history provided the setting for his tales of Colonel Falkenberg and also A Spaceship for the King. He also used this universe in collaborating with Larry Niven, where it served as the setting for the groundbreaking novels A Mote in God’s Eye and The Gripping Hand, among the best tales of first contact that have ever been written. S.M. Stirling also co-wrote stories set in the CoDominium era, and the War World shared-world anthology series also takes place within this universe.

Niven and Pournelle helped increase science fiction’s profile in the literary world with a series of best-selling books, with the cometary disaster novel Lucifer’s Hammer reaching #2 on The New York Times Best Seller list and alien invasion novel Footfall reaching #1. Other collaborations between the two included the horror-influenced novel The Legacy of Heorot (with Steven Barnes) and the allegorical novel Inferno. One of Pournelle’s best series, in my opinion, started with 1979 Janissaries, which followed a group of mercenaries kidnapped by aliens for service on a far-away planet. Later volumes were co-written with Roland Green, and supposedly, a fourth volume, Mamelukes, is largely complete, and will hopefully become available at some point.

With the aid of John Carr, Pournelle also produced several science fiction anthology series, including There Will Be War and the previously mentioned War World. The anthologies include many noted authors, but Pournelle and Carr also allowed a number of unknowns to see their work in print, and as one of those unknowns, I will always be grateful.

From 1973-1974, Pournelle served as president of the Science Fiction Writers of America. By all accounts, he was a passionate defender of the rights of writers, and aggressive in dealing with publishers. He also served as one of the stewards for the SFWA Emergency Medical Fund.

Pournelle was a man of strong political beliefs. While he did not hew to any specific political doctrine, other than his own, his views often skewed far right of center. He was fierce in defending his ideas and in attacking critics, and developed a reputation as a curmudgeon on electronic media even before the Internet was as widespread and all-encompassing as it is now. Because of his politics, he was a polarizing figure within the science fiction community, drawing strong reactions from many of his peers. For myself, while I often strongly disagreed with his opinions and conclusions, I always learned something from his vigorous defense of his ideas.

A Spaceship for the King

The book opens in a bar, where young Lieutenant Jefferson and two friends from the Imperial Navy are celebrating a great victory. They have assisted the forces of King David of Haven in defeating their foes, hastening the consolidation of power on the planet of Prince Samual’s World under a single government. This is a prerequisite for the planet’s entry into the Empire. Jefferson also lets slip the information that planets are incorporated into the Empire in categories based on their level of technology—specifically their ability to achieve spaceflight. Obsessed with establishing order and preventing future wars, the Empire gives inhabited worlds only two options: join the Empire on the Empire’s terms, or be destroyed.

The book opens in a bar, where young Lieutenant Jefferson and two friends from the Imperial Navy are celebrating a great victory. They have assisted the forces of King David of Haven in defeating their foes, hastening the consolidation of power on the planet of Prince Samual’s World under a single government. This is a prerequisite for the planet’s entry into the Empire. Jefferson also lets slip the information that planets are incorporated into the Empire in categories based on their level of technology—specifically their ability to achieve spaceflight. Obsessed with establishing order and preventing future wars, the Empire gives inhabited worlds only two options: join the Empire on the Empire’s terms, or be destroyed.

Across the bar, unnoticed by the oblivious Imperials, ex-Colonel Nathan MacKinnie sits drinking heavily with his former sergeant, Hal Stark. MacKinnie was the leader of the military forces of Orleans when Imperial intervention with advanced weaponry led to their total defeat. MacKinnie is an archetype for many of Pournelle’s protagonists: an older military man who has suffered a political setback or whose sage advice is ignored, but who still possesses the knowledge and ability to prevail. Stark is also a familiar figure, the noble sergeant major who is the cornerstone of the unit. Furthermore, the planet of Prince Samual’s World is heavily influenced by Scottish culture, another element that often appears in Pournelle’s work.

Upon leaving the bar, MacKinnie and Stark are kidnapped by members of Haven’s secret police, and taken to Malcolm Dougal, a shadowy advisor to King David. He tells MacKinnie that his forces have learned about the categories used by the Empire and that spaceflight capability is the key to autonomy for worlds within the Empire. The Imperial traders have invited a contingent from Prince Samual’s World to accompany them to the primitive world of Makassar, and Dougal has learned that an electronic library from the First Empire still survives in a temple on that planet. If Haven can drag their feet, delaying further consolidation of political power until someone successfully brings back the information from that library, Prince Samual’s World could demonstrate space flight and be consolidated into the Empire as a somewhat autonomous world instead of a colony. Dougal believes that MacKinnie is just the man to masquerade as a trader and lead the expedition to Makassar.

MacKinnie agrees, and the expedition soon includes not only himself and Stark plus a pair of guards, but also Shipmaster MacLean of the merchant services, Academician Longway, a professor specializing in primitive cultures, Scholar-Bachelor Kleinst, a physicist, and Freelady Mary Graham, an intelligence agent who will serve as secretary for the expedition. While Prince Samual’s World is at a nineteenth-century level of technology, Makassar is more primitive, closer to the level of the Middle Ages, and the expedition will not be able to bring any firearms with them. The Empire, obsessed with order, is concerned about introducing “new” technologies that might disrupt a world’s culture and stability.

The team trains for success, and during their transport, they learn quite a bit about Imperial space technology, although they find the new insights disheartening, underscoring the disparity between the Imperial tech and their own comparatively basic technical knowledge and capabilities. When the expedition arrives on Makassar, they check in with the Imperial base in Jikar, a trading town on the coast. They are told that if they plan to return on the same ship, they will only have three days for trading—and the next ship will not be available for a year. With no better option, the team grudgingly agrees to stay for a year, as the library they seek is in the city of Batav. In the meantime, they find that the world is in turmoil, with barbarians restricting travel on land and pirates infesting the seas.

The team obtains a ship, and MacLean begins to modify it to suit their needs, changing the rigging and installing lee boards. They find a local sea captain, Loholo, desperate enough to aid them; he helps to raise a crew and train them on military tactics. They also meet Brett, a wandering bard, and Vanjynk, a knight errant, who agree to act as local guides. They set sail, and their modified vessel proves superior to the pirate ships. They are beached by the fierce tides of the planet, however, and must fight a pitched battle with some of the pirates, during which MacKinnie’s tactics win the day. These sea scenes crackle with energy, and suggest that Pournelle, in addition to his knowledge of nautical history, also has some real life experience on sailboats.

Arriving at Batav, they find the temple guarded by highly disciplined swordsmen, and the city besieged by nomadic barbarians. Even if they could find their way into the temple, the city might not survive much longer. MacKinnie, after assessing the situation, brings a proposal to the temple elders: if they will give him a chance to train and organize the inhabitants of the city who depend on the temple’s charity, he will organize a force that can help lift the siege. It will be no surprise to the reader to find that MacKinnie succeeds in his task—exactly how he does that, however, is a big part of the fun of reading the book, and thus I will not spoil it. Suffice it to say that Pournelle is at his best when describing the forging of a military force and their use in combat. As a result of his skill and effort, MacKinnie and his team get access to the library that could be the key to their planet’s future.

At this point, the shorter tale of A Spaceship for the King ends. The later, expanded version of the novel, King David’s Spaceship, however, is about a third longer, and the additional third turns out to be one of the best parts of the story. The early portion of the book takes place before the events depicted in A Mote in God’s Eye, but in the final portion of the novel, we see the discovery of the Moties and subsequent naval redeployments impacting the actions of the Imperial forces. In King David’s Spaceship, we learn how the scientists of Prince Samual’s World use the information they have gained from MacKinnie’s expedition to Makassar; after realizing that their technology will require a new and different path, they end up employing concepts that owe more to Jules Verne than NASA. At the same time, we also witness King David’s forces playing one Imperial faction against the other in order to gain political advantage.

This book is among Pournelle’s earliest works, but it contains many of the key elements and themes that he used throughout his career. We encounter political systems that are anything but utopian, military adventure, and a keen appreciation of technology and its impacts. Pournelle is sometimes viewed as a pessimistic writer, but his stories also contain a core of hope—those who are brave, dedicated, clever, and loyal to their comrades can prevail, even when the deck is stacked against them.

Final Thoughts

Jerry Pournelle was one of those people in the SF community who was simply larger than life. He was a marvelous writer, composing tales that entertained and enlightened. If I could choose one word to describe the man, it would be as a fighter: fierce in defense of his friends and his ideas, and a fierce opponent to any foes. I offer my condolences to his widow and his family for their loss.

And now it’s time to turn the floor over to you. What are your thoughts on A Spaceship for the King, or if you like, any other works by Pournelle? And do you have any stories you would like to share about the man himself? Having already established the fact that not all of us agree with his political views, this is not the time to re-litigate old arguments or disputes—instead, let’s take this opportunity to look back at the career and contributions of a man who had a huge influence on the science fiction field.

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for over five decades, especially fiction that deals with science, military matters, exploration and adventure.