When faced with posterity’s lottery, artists might hope they have one work at least which finds favour with future generations. In the case of Swiss painter Arnold Böcklin (18271901) this would be Die Toteninsel (The Isle of the Dead), not a single picture but a series of paintings produced from 1880 to 1886 all of which depict a similar scene. The enduring popularity of the pictures wouldn’t have surprised Böcklin, he painted the four additional versions after the original proved surprisingly popular.

What’s fascinating about the paintings is the spell they’ve cast over subsequent generations of artists, musicians, writers and filmmakers. The quality of mystery which Böcklin evoked is a specific attraction for those drawn to the eerie and the fantastic. In this post we’ll look at a few of the more notable derivations.

All five paintings of The Isle of the Dead (hereafter named according to the galleries where they reside) show the same small Mediterranean island with tombs and a stand of cypress trees. Towards each isle a boat is being rowed bearing a coffin and an upright figure clad in white. In the first version (Basel) the view is light and airy: the isle is caught by a setting sun which makes the white of the tombs leap to the foreground. As the series progresses the scene turns increasingly sombre until in the final version (Leipzig) the rocks have grown taller and darker, storm clouds are gathering, and the standing figure is hunched in an attitude suggestive of grief. Version three (in Berlin) was owned for a short time by Adolf Hitler while version four was destroyed during the Second World War. Böcklin’s mortuary island is itself partially deceased.

The atmosphere of stillness and mystery was deliberate, Böcklin wanted “a picture to dream over.” The funeral boat was absent from the original, that detail arriving after a widow expressed an interest in the painting and requested something be added to it to remind her of her late husband. Böcklin painted a copy (now in New York) and added figures to both the pictures. The title of Isle of the Dead was the suggestion of an art dealer, the artist always referred to the scene as The Tomb Isle.

The first derivations were also pictures: a younger German artist and Böcklin obsessive, Max Klinger, made an etching based on the Berlin version. After Böcklin’s death another acolyte, Ferdinand Keller, painted a memorial, The Tomb of Böcklin, which alludes to the island, its tombs and its cypresses, without being an overt copy.

In the music world Heinrich Schülz-Beuthen in 1890 then Rachmaninoff in 1909 composed works inspired by the painting. Rachmaninoff’s gloomy symphonic poem lasts around twenty minutes and acquires a funereal cast with the introduction of the Dies Irae theme near the end. Böcklin’s style of Symbolist art fell out of favour around this time but interest in the Symbolists was revived by the Surrealists in the 1930s. Salvador Dalí in 1932 painted The Real Picture of the Isle of the Dead by Arnold Böcklin at the Hour of the Angelus, but the artist leaves us to work out the connection between the title and his scene of an empty beach.

Of greater interest a year later is the film King Kong which we’re told borrowed Böcklin’s isle for the distant views of Skull Island although I’ve never seen a definite confirmation of this. King Kong was an RKO production and it was at RKO that the painting makes two of its most memorable film appearances. Producer Val Lewton had a curious obsession with the picture, first using it in the background of scenes in I Walked with a Zombie (a story about another isle of the dead), then lifting painting and title for the 1945 film The Isle of the Dead. Mark Robson’s film is a war-time thriller featuring Boris Karloff which takes place on a rocky, tomb-ridden island.

The isle-as-setting recurs again in The Tales of Hoffmann in 1951, a filmed adaptation of the Offenbach opera by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger. The third act, “The Tale of Antonina,” is set on a Greek island whose exterior is a replication of Böcklin’s view.

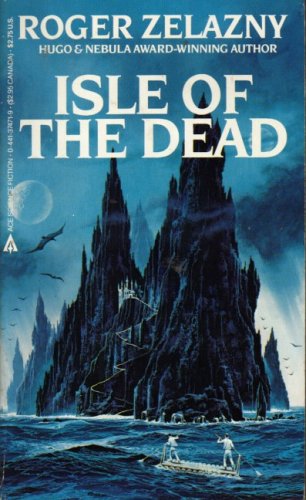

Up to this point all the derivations are either homages or variations on Böcklin’s theme. Roger Zelazny went a lot further in his 1969 novel Isle of the Dead which relocates the island (or a version of it) to a distant planet. I haven’t read this but looking for cover designs it’s surprising to find how few books bother to take their cue from any of the paintings.

In the 1970s HR Giger produced several Böcklin-influenced pictures including two isles of the dead. The first, from Giger’s ‘Green Landscapes’ series, copies the Leipzig painting and adds a mechanism from a waste-disposal truck which had been obsessing the artist. The second version employs his biomechanical style and looks alien enough to work as a cover for Zelazny’s novel.

After Giger the derivations in comics and fantasy art really start to proliferate so we’ll fast-forward to 2005 and The Piano Tuner of Earthquakes, a feature film by the Brothers Quay set on a Mediterranean isle which is Böcklin’s in all but name. The film connects obliquely to Powell & Pressburger with a Hoffmann-like tale of a sinister automaton-maker, Dr. Droz, and an abducted opera singer who everyone thinks has died.

What is it about this view which continues to inspire so many creative people while the artist responsible remains comparatively unknown? Böcklin has fixed a powerful image of an edge, a border, somewhere caught between sea and land, calm and storm, day and night, life and death, reality and fantasy. Salvador Dalí once said “The quicksands of automatism and dreams vanish upon awakening. But the rocks of the imagination still remain.” The rocks of Böcklin’s imagination continue to draw us towards their enigmas.

For those who’d like to pursue the mystery further, Toteninsel.net is the place to start. Val Lewton’s obsession with the painting is detailed here.

John Coulthart is an illustrator and graphic designer. His collection of Lovecraft comic strip adaptations, The Haunter of the Dark and Other Grotesque Visions, is published by Creation Oneiros.