R.A. MacAvoy is a very, very fine writer, and far less well known than she deserves to be. She’s also a horse person of the true and deep-dyed variety. When she writes horses, you can trust her.

My favorites of all her books are the three volumes of the Damiano trilogy (Damiano, Damiano’s Lute, and Raphael), historical fantasy set in Italy (and Spain and Lappland) in the early Renaissance. With an archangel. And an adorable dog. And an elegant, not very bright, not very graceful, but very well bred black gelding named Festilligambe (Sticklegs), who is not a major character, but he features prominently in the story.

But this not a series about horses, and I’ve been following a sort of theme in this summer’s reading adventure. Therefore, because I wish more people knew about this author, and because it’s just plain a delight, I’ve dived back into The Grey Horse after a long time away.

The thing to understand about this book is that the protagonist is written from life. As MacAvoy said in an interview a few years ago, “I raised Connemara ponies for many years, and Rory was actually a character portrait of a small stallion I had, who was really named Emmett. He has a lot of descendants over California. All in pony form.”

That last disclaimer is important. Some horses go above and beyond when it comes to personality, and there’s something literally weird about them. When they’re of a breed that’s as Irish as the stones of Connemara, it’s not too far off to speculate that they have at least a little puca in them.

(I should state for the record that I have a small grey horse nicknamed Pooka. Because when he was born, and he rolled that big dark eye at me, I knew what he was. He is not Irish, at all—he’s Spanish and Arab by way of Austria—but magically wicked horse-spirits are not confined to the British Isles. He is very clever, unlike Ruairi, but…yeah.)

It had been more than long enough since I last read The Grey Horse that I had forgotten just about everything, so coming back to it was like reading it for the first time all over again. And it was just as delightful as before (that part I did remember). It’s an utterly Irish book, in its wry humor and its slightly tilted angle on the world; magic is real and a matter of everyday, but so is the Church and the faith that pervades the island. The fairy folk still dance in their raths, while the saints and the angels rule over the churches.

This is also a horse person’s book, totally. Its human protagonist, Ainrí (or Henry—homage perhaps to the beloved character in the Black Stallion books?), is a horse trainer, mostly of racehorses but he takes any work he can find. He lives in Ireland in or around the 1880s, after the great potato famine but well before independence, and insurrectionists are very much a part of the background. So are the English overlords, including one named Blondell, who fancies himself an Irishman, makes efforts to speak the language, but reverts to Englishness when subjected to pressure.

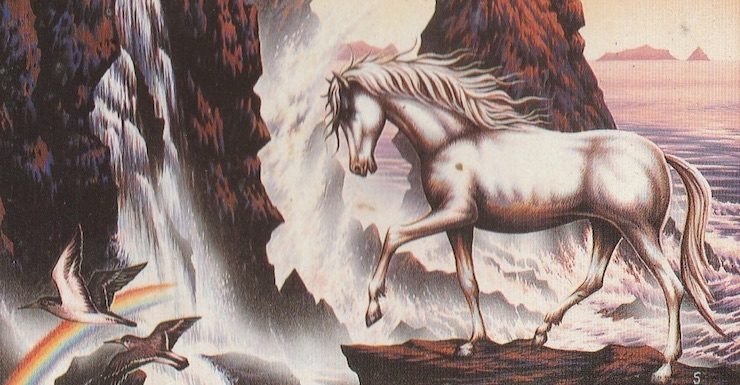

One fine day, Ainrí encounters a stray grey horse on the hilltop, and allows himself to be persuaded to mount the horse—who then carries him off on a long, wild ride. Ainrí is a splendid rider, so manages to stay on, but he has no control over the horse whatever, until he finally manages to get a rope halter on it (because Ainrí is never without this essential tool of his trade). Then the horse submits, not happily, and Ainrí takes him into his stable. Because if you want to bind a magical horse, of course you need a bridle—golden for Pegasus, or plain ordinary rope for a puca in Connemara.

Because the horse is not really, or completely, a horse at all. He reveals himself in a harrowing scene, after getting into a battle with Blondell’s dimwitted and brain-fried but terribly valuable Thoroughbred stallion, when Ainrí and his trusty sidekick Donncha decide to do what one does with feral male horses of unknown ancestry to make them fit for human uses.

There’s some considerable startlement among the humans, but this being Ireland, they quickly settle down and take it in stride (and refrain from gelding the stallion). Ruairi is useful in numerous ways; he manages to tame the batshit Thoroughbred and teach Blondell’s young and misfit son Toby to ride, and even makes some reasonable sense out of the Thoroughbred’s equally dimwitted and hairtrigger young daughter.

He is here, he tells Ainrí and Ainrí’s redoubtable wife Aine, for love of a woman in the town. Maire Standun (Mary Stanton—homage again to a fellow writer of fantasy horses?) is a splendid specimen of a woman, and she is not her putative father’s daughter; her mother had an affair with one of the fair folk. Ruairi is madly in love with her and intends to make her his wife.

Maire isn’t at all on board with this. She has her own life, helping the local parish priest foment insurrection and coping with her cold-hearted stepfather and her too-beautiful blonde half-sister. But Ruairi, though he insists he is not clever, is persistent. He courts her, builds her a house, and even, because her father won’t give her to any but a Christian man, submits himself to baptism.

Buy the Book

The Grey Horse

That is a terrifying ritual for one of the old people. Ruairi’s two selves—the human and the horse—are nearly ripped asunder, but the priest is of the old blood himself, and manages to put them back together before it’s too late. And so Ruairi renders himself fit to claim his love.

But not before Ainrí and Blondell settle their differences in a mad race through the countryside, the red stallion against Ruairi in horse form. Ruairi is not a conventional racehorse, being short, stocky, and relatively common-looking, but he is also magical. The race ends in victory for Ruairi, but tragedy for the Thoroughbred and also for Ainrí : the horse runs himself to death, and Ainrí succumbs to a heart attack. But it’s the ending both of them would have wanted.

In the aftermath, at Ainrí’s funeral, the authorities appear in search of the tax man, who has vanished. That is Ruairi’s fault: they came to blows and he killed the man and buried him deep, where no one will ever find him. Ruairi saves the day, however, and drives the agents of the oppressor away, and wins his headstrong bride.

For a writer looking to find examples of solid horse-lore, this is an excellent source. Ainrí’s calm and casual skill, the combination of exasperation and affection with which he regards his equine charges, and the ways in which he conducts himself both on and around horses, are pure old horse trainer. Maire who is not a rider but who manages to cope when Ruairi carries her off, and Toby who evolves from timid to confident rider under Ruairi’s tutelage, demonstrate two levels of inexperience and two ways of approaching it.

Ruairi plays well as both horse and not-quite-human, except for one thing. No stallion is monogamous. They have favorites among their mares, but they are made by nature for polygamy. It’s not likely a stallion will fixate on a single mare (or Maire).

Then again, Maire is human, and a horse can be a one-woman horse. So there’s that. Though over the years she might wonder about some of the foals running wild through the local pony population.

I loved this reread. Laughed aloud in parts—especially Ainrí’s ride in the beginning—and settled in with great contentment for the many examples of horses written well. The cast of characters is classic MacAvoy: wonderfully drawn protagonists on all ends of the age spectrum. The setting is richly and deeply felt; the history is solid. The magic is inextricably bound with that setting, and born of it. It manifests in the form of the puca who loves a (half) human woman and lives happily as a horse.

Ruairi may not be clever, or so he says, but he always manages to get the better of the bargain, whatever he’s up to. I suppose that’s to be expected when you’re 1500 years old and the son of Irish granite and the wind.

Some of the regulars in the comments will be glad to hear that I’m reading The Heavenly Horse from the Outermost West next. More horse magic, and another Mary Stanton, this time as the author of the book. How could I not?

Judith Tarr is a lifelong horse person. She supports her habit by writing works of fantasy and science fiction as well as historical novels, many of which have been published as ebooks by Book View Cafe. She’s even written a primer for writers who want to write about horses: Writing Horses: The Fine Art of Getting It Right. Her most recent novel, Dragons in the Earth, features a herd of magical horses, and her space opera, Forgotten Suns, features both terrestrial horses and an alien horselike species (and space whales!). She lives near Tucson, Arizona with a herd of Lipizzans, a clowder of cats, and a blue-eyed dog.

‘You know that feral stallion I caught? Turns out he’s actually a Pooka. Nice fellow, very helpful.’

“Really? Must be convenient.”

“Oh it is.”

One of my favorite books by one of my favorite authors. It’s been my comfort read through many a hard time. The baptism scene I think is my absolute favorite — especially the struggling priest, and the confused housekeeper who is trying to figure out why there are hoofmarks in the hardwood floor.

I’ve never heard of this book! Now I’ll have to see if i can find a copy. :)

@1 Sure is convenient. The training string all snap to attention, and he can sleep in the stable and you don’t have to feed him; he grazes like the rest of the horses.

@2 That is a truly epic scene. Hilarious and spectacular at the same time.

@3 It is a treat, it is. My favorite reread is Raphael, but this is lovely.

I’ve loved almost everything I’ve read by Ms MacAvoy. She is, as Ms Tarr says, a very fine writer. I don’t know what happened, but she seemed to disappear and hasn’t reappeared on my the shelves of the local chain or independent bookstores.

Alas, I’ve not read this book.

Can Tor bring her back to the shelves?

Please?

@5 She had a long hiatus because of severe health problems. Has recovered enough for the past few years to write, but has been publishing via small presses. You can find her work through web searches.

The problem with older writers who did not hit the big time and stay there is that there is no longer interest among the major publishers, who are busy keeping big-timers in print and publishing newer writers. There are only so many slots, and the current model, which is all about the bestsellers, does not favor authors with smaller-than-bestseller appeal.

They can however be found among the smaller presses, or self-publishing. They won’t show up on your local indie’s shelves as a matter of course, but it’s possible they can be special ordered. Or you can find their work via online retailers.

Can’t wait for the heavenly horse, which I literally read to shreds!

I never got into of MacAvoy’s other books, but I read this one early and I loved it. I understood the fairies and horses straight off; I had to go back years later for the politics.

I never did read this one, but I loved the Damiano books and the Lens of the World trilogy.

FWIW, it looks like pretty much her entire catalog is available in eBook format (and many of them currently reside on my Kindle).

I love the Black Dragon books. Tea With was where I met MacAvoy. I love The Gray Horse. I love The Book of Kells. The Lens of the World books are great.

The Damiano Trilogy never made it to my reread list. De gustibus and all that.

Some of the regulars in the comments will be glad to hear that I’m reading The Heavenly Horse from the Outermost West next.

And also the sequel, Piper At the Gate? Although to my mind, that’s a lot darker than Heavenly Horse.

Oh thank you thank you! I am going to rush out and get this book just on the strength of your review. My number one pet peeve with historical novels is the total failure of most writers to understand that horses are not cars. I have known so many horses with larger than life personalities. In fact, looking back over a life that at this point stretches half a century, I would have to say that my horses stand out far more vividly in my memory than most humans I’ve known. Especially their senses of humor and mischief, which very few non-horse people are aware of. I still find myself laughing sometimes over the practical jokes and devious stratagems of horses gone these thirty years and more. And the ponies are the worst of course! I am convinced that when it comes to machiavellian maneuvering the average pony is far, far smarter than the average human. Can’t wait to meet this fellow!