In “Advanced Readings in D&D,” Tor.com writers Tim Callahan and Mordicai Knode take a look at Gary Gygax’s favorite authors and reread one per week, in an effort to explore the origins of Dungeons & Dragons and see which of these sometimes-famous, sometimes-obscure authors are worth rereading today. Sometimes the posts will be conversations, while other times they will be solo reflections, but one thing is guaranteed: Appendix N will be written about, along with dungeons, and maybe dragons, and probably wizards, and sometimes robots, and, if you’re up for it, even more.

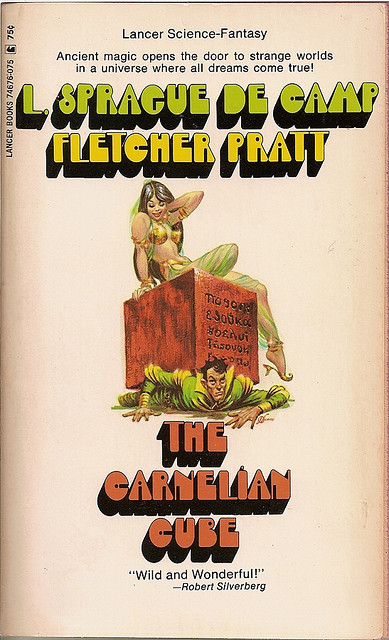

Welcome to the tenth post in the series, featuring a look at The Carnelian Cube by the prose tag-team of L. Sprague de Camp and Fletcher Pratt.

Mordicai Knode: Here we go again. Neither of us was very keen on Lest Darkness Fall, and frankly, The Carnelian Cube is more of the same, even with the addition of a co-author. I mean, I haven’t finished the book yet, so there is a chance for the story to take a sudden right turn and surprise me, but I doubt it will happen. In fact, The Carnelian Cube might even be a worse offender; part of what made Lest Darkness Fall so frustrating was the inherent misogyny of the story, but there the sexism is largely related to the romantic subplots. Here, the romance is sort of the main frame of the story—or at least, it holds up each of the repeated vignettes—which makes the whole “women as explicit objects” stand out all the more.

See, I get it, L. Sprague de Camp. You’re a cynic. I’m just exhausted by all this cynical fiction; I yearn for the “gee whiz!” of some of the other pulps, I guess. See, in Lest Darkness Fall, the gimmick of the story was that the protagonist—a upper crust academic white dude—is thrust into the end of the Roman Empire. In Carnelian Cube, an upper class white academic is…also thrown into a fish out of water scenario. In this case, it is a series of worlds linked by his imaginings—a world where reason flourishes, or where individuality is the watchword of the civilization—each given a dystopian twist. I will say this: it makes the “modern day humans thrown suddenly into a fantasy world!” elevator pitch of the Dungeons & Dragons cartoon make a lot of sense. Then again, so does Three Hearts and Three Lions, which I preferred.

Tim Callahan: This book demoralizes me. I can confidently say that it’s the worst book out of the entirety of Appendix N, and I haven’t even read all the books yet. I’m sorry to say that nothing happens in the last half of the book to save it, but it does spiral downward into its own abyss of humorlessness, so you have that to look forward to. And here’s the thing: L. Sprague de Camp and Fletcher Pratt are trying ever so hard to make this book hilarious. You can see it in every scene. They must have seen this book as nonstop laughs, because it has all the hallmarks of a comedy, with its ridiculously exaggerated characters and its sitcom-like set-ups and the unrestrained use of dialect. I mean, what could be funnier than characters who talk like local dinner theater actors in an oh-so-clever performance of Colonel Sanders Presents the Best of Mark Twain as Recited by Guys Who Were Known as Third-Rate Jim Varney Impressionists?

Practically the whole book is like that.

If Lest Darkness Fall was a riff on A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, but with more pedantic history lessons thrown in—and it was—then The Carnelian Cube is de Camp and Pratt’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn plus their nerd-snobbery brand of satire and minus any redeeming qualities whatsoever.

I can’t believe how much I despised this book. But I really did. After the first chapter, which is just your standard set-up of “hey, here’s this weird artifact” and “what a weird dream” it just keeps getting worse and worse until the whole thing escalates into what I can only imagine is the equivalent of the worst 1980s Rodney Dangerfield movies that don’t even show up on cable any more.

You know what The Carnelian Cube is? It’s a Grand Guignol of the unfunny.

MK: Wait, did I just read a serious and straight-faced piece of Anti-semitism in this book? I mean, I was already like—“oh look, the people who aren’t white in this book are a bunch of second-class citizens and buffoons, but at least all the white people are buffoons too”—but then there was a…screed about miscegenation? Out of the mouth of one of the supporting characters, at first, but then the…protagonist steps in to help him refine his ideas of how the Jews and race mixing were to blame for the Assyrians? I kept thinking that the main character would contradict him, or at least have an internal dialogue about it, but sheesh! Nothing doing. You know, for a book originally published in 1948, that is…just, wow. Wow in a bad way. Hashtag Shaking My Head.

The book is sort of like, “what if Mel Brooks wasn’t really funny, and also was a huge misogynist?” Actually, the women in the story really work in that analogy; Mel Brooks also as a little bit of a ribald sense of humor (“a little bit” may be an understatement) and so his movies hinge on sex quite often, as well as historical gender roles. Mel Brooks, however, lampoons that, while at the same time still having, you know, jokes about Vestal Virgins. L. Sprague de Camp and Fletcher Pratt on the other hand would take the same opportunity and use it as an excuse to demean women, maybe have their protagonist bully and coerce someone, and sort of grin rakishly like “ain’t I a stinker?”

Yeah, Carnelian Cube. You are. You stink.

TC: I don’t know how else to talk about this book except to not talk about it, so I’m going to head in this direction: why do you suppose this book ended up on Gygax’s Appendix N list?

Other than the cube itself, which acts as a kind of alternate-reality hopping TARDIS-sans-quality, there’s little in the way of sci-fi or fantasy trappings in this novel. Not in any recognizable way that could have influenced a role-playing game. It is like a series of terrible Mel Brooks scenes written by computer science nerd who had only read about Mel Brooks scenes and also hated almost everything and thought that southern accents were inherently hi-larious.

But the cube is just a storytelling conceit and it doesn’t have any special powers in the way that a D&D magic item might—it can’t really be used, but rather it just propels its subject from one alternate reality to another, yet more non-hilarious and likely-very-offensive, alternate reality.

Maybe that’s the thing. Maybe that’s Gary Gygax’s sweet spot. He did base an adventure on his heroes bumbling down through a portal into a warped version of Alice in Wonderland. That was what he liked to see: some physical humor and some viciousness and something that we wouldn’t likely recognize as comedy. But only in small doses. Most of his adventures weren’t really like that. Or maybe they were. The fact that he goes out of his way to name not just these two authors, but The Carnelian Cube specifically as recommended reading is one of the great mysteries of Appendix N.

MK: Well, personally I think it is a factor of a couple of things at work; some petty, some rather insightful, actually. Well, not in the text—as established, a pretty terrible book—but in what I imagine Gygax’s reading of the text to be. First, there is the eponymous cube, which is a pretty viable template for a D&D artifacts, or at least a big influence. A classic MacGuffin. Secondly, there is the issue of perverting wishes; you know that is some Gygaxian flavor right there. If you give your players a Ring of Wishes, you are obligated to try to misinterpret them…the same way that the carnelian cube’s created dream worlds are pessimistic inversion of the users original intentions.

The other is in terms of worldbuilding. I think that glomming on to a high concept idea like “a world where pitiless logic wins” or “a world of individualism taken to the extreme” and spilling it out for a few chapters is actually a solid Dungeon Mastering trick. I mean, look at Star Trek’s Vulcans; they are basically just elves with “logical” thrown on as a cultural gimmick, right? That sort of tactic is a good way to add colour to your newest fantasy metropolis, or tribe of non-humans, or alternate universe. It might be a “cheap trick,” being a little inorganic, but as someone who runs a game let me just say that sometimes, cheap tricks are the best.

Still, not a good enough reason to read this book, though.

TC: And, as someone else who regularly runs games, I’ll say that silly accents go right along with single-minded high-concept NPCs, and Carnelian Cube is nothing if not full of those things. And I’ll second all of your remarks. Especially the part about not reading this book. Or recommending it. Or ever mentioning it again.

Tim Callahan usually writes about comics and Mordicai Knode usually writes about games. They both play a lot of Dungeons & Dragons.

I should note though: I for one am all for silly accents.

Silly accents ARE the best. In games. And in life. Not so much in novels.

@mordicai and Callahan: I read de Camp’s SF novels Genus Homo and Rogue Queen a short while ago but I can’t remember the first thing about either of them. I was also going to put in a word for the Compleat Enchanter stories, however, I remembered Larry Niven’s The Flight of the Horse, which does similar things, only in a manner I found more entertaining.

3. SchuylerH

Yeahhhhhhhh after this one & Lest Darkness Fall, I’m pretty all full on giving this guy a chance. Niven on the other hand is a whole different kettle of fish, a horse of a different colour!

@@.-@: There are a few Niven books of interest: The Flying Sorcerers (with David Gerrold) is impossibly silly. The Dream Park books (with Steve Barnes) are about playing games, albeit LARPs rather than RPGs.

The Magic Goes Away features the neat concept of magic being a non-renewable resource and was followed by two multi-author anthologies. Contributors included Fred Saberhagen, Poul Anderson, Bob Shaw and Niven himself.

The Flight of the Horse collects five stories about the hapless Svetz, sent back from a polluted Earth to collect various animals from the distant past. Of course, he has only a fragmentary idea of what he’s looking for, so he doesn’t ask questions when the horse he’s trying to pick up has a prominent horn growing from its forehead…

“a world where pitiless logic wins” or “a world of individualism taken to the extreme” both sound like actual outer planes.

6. fordmadoxfraud

This is true! Except I think Mister Gygax had a bigger imagination than these authors, because he sure filled his Hell & Abyss with compelling figures absent from this work.

I had this book once, way way back. I don’t know what de Camp and Pratt were thinking here – it reads like a poor copy of the Harold Shea series. Recycling rejected stories, maybe?

I can’t find my AD&D DM’s Guide right now (darn those kids… well at least they’re getting use out of it), but did they refer to “Carnelian Cube” by title, or just the authors? Because of the DeCamp/Pratt works, I’d have thought it would be the “Compleat Enchanter” stories, which bring a mathematician into fantasy/mythic worlds (geez, couldn’t they come up with a plot other than fish-out-of-water?).

Aha, yes, the internet reveals that it lists the “Harold Shea” stories too. These were published as “The Incomplete Enchanter”, later with another story added as “The Compleat Enchanter” followed with “The Wall of Serpents” and later as an omnibus “Complete Compleat Enchanter.”

Note also that one of the stories, “The Green Magician” was reprinted in the two issues of The Dragon magazine starting with June ’78, and Tom Wham, one of the central TSR writers and artists, wrote a choose-your-own-adventure set in the Shea setting, called “Prospero’s Isle”

Go on guys, tell us what you *really*think about it :p

I have a soft spot for the Harold Shea novels, but I definitely remember not liking this one. It never shows up in second hand either, which says something

10. Mayhem

9. joelfinkle

Yep, it is “de Camp & Pratt: “Harold Shea” series; THE CARNELIAN CUBE.” Which…I guess the temperature of the room says that we picked wrong, since so many of you have a fondness for the Enchanter tales.

You know, I forgot to mention this: I bet the biggest influence of this book is Gary Gygax using a d6 as a prop. DnD is full of that silliness (see also, the cubic gate &…modrons, period.)

I did indeed love the Compleat Enchanter stories when I read them. But now, I’m a little worried the Suck Fairy will turn out to have visited them.

Funny accents ARE a De Camp and Pratt thing. I recall them vividly in The Incompleat Enchanter, when you have Brooklynese accented Norse Trolls. No, really.

Tim Callahan: This book demoralizes me. I can confidently say that it’s the worst book out of the entirety of Appendix N, and I haven’t even read all the books yet.

?

Somehow I missed this book back when it was new, and after this review, I don’t think I missed much…

13. JohnArkansawyer

Oh god, I’m so sorry, it is the WORST fairy. Like, if you remember Changeling: the Dreaming, like Dauntain bad.

14. PrinceJvstin

Well, when you say it like that, it is worth pointing out that Tolkien’s trolls have…well, I bet an English person could tell you what kind of dialect.

16. AlanBrown

I super appreciate that viewpoint, if I haven’t mentioned that. I’m pretty spry for a guy in my thirties, but I don’t have the immediacy & cultural context of what it was like RIGHT THEN, right when it was coming out. As Tor’s Cory Doctorow books show, sometimes that is really vital.

This reminds me that, back in the day, there was not a lot of SF/F available. And a lot of it was crap.

GG’s pickings were relatively slim.

yet another vote for the Compleat Enchanter series here. Not perfect by any means, but a much better story/series of stories than the Carnelian Cube…and you really should read something decent by them!

@17: I believe that the troll accent is held to be cockney but I suspect it’s really just about Tolkien’s dislike of colloquial speech in general.

18. sps49

Living in the future is totally boss.

19. worthy

Maybe Tim & I will do an “okay so you said we should read…” follow-up!

20. SchuylerH

I would have guessed Cockney, but then…where is the rhyming slang!

If you had a choice between the Harold Shea series and the

The Carnelian Cube, you chose the wrong one. The Harold Shea series reads like a D&D adventure, and I love the stories and have read them many times. The Carnelian Cube I read once and never bothered again.

The first story in the series might not have the problem with women (it’s been a long time since I read it, so the suck fairy might have visited since I was in my teens). There are no major female characters (there might be a barmaid, and Hel shows up briefly at the very end).

IIRC the remaining stories do have the ‘female as prize’ trope however. The second story does have the originiation of the D&D web spell and its reaction to flaming swords.

@21: I said held to be. I see it as Tolkien’s interpretation of generic colloquial urban English.

23. SchuylerH

I was just at drinks– I’m going on vacation, so this was like my Friday!– where I ranted about trying to understand the Brits & slang & slurs. No dice. Anyhow, I think this is a good point to invoke Planescape & the jargon of that brilliant setting.

I think you need to give “The Roaring Trumpet” (the first of the Harold Shea stories) a writeup. I don’t know anyone who thinks that The Carnelian Cube is a major work and I’m amazed that Gygax listed it by name; but as noted here, Harold Shea is one of the most important fictional influences on D&D. (I’d put them behind Leiber, Howard, and Tolkien, but roughly tied with Vance, Moorcock, and Anderson.)

Yes, the sexual politics in the later stories aren’t good, although the girl-as-prize is also a kick-ass warrior woman, which was quite rare for too long.

26. womzilla

Well this is some overwhelming encouragement to read the Shea books– there were others talking about it on Twitter & so-&-so. Alright, I mean, I disliked the first two books that I read of his but you are all pretty ardent!

Well, Gygax did create the drow — a society of malevolent women with problematic racial overtones. Maybe he liked the stuff we all find appalling?

Just my two copper pieces’ worth: Totally agree about The Carnelian Cube (and The Blue Star). Couldn’t finish either of them, and I have no idea in what way The Carnelian Cube inspired AD&D. I think quite a few of the authors and books in Appendix N are just ones Gary enjoyed at the time, rather than specific influences (Weinbaum? Williamson?). I could wax unlyrical about de Camp (but will restrain myself this time) as I’ve read most of his Howard pastiches and truly despise them (and I really like Howard when he’s at his best). The nicest thing I can say about de Camp is that without him (and Frazetta, but that’s a separate story) it is highly unlikely Howard would be the recognized author he is today – de Camp is to Howard what Derleth was to Lovecraft.

I think we all have a tendency, to a greater or lesser extent, to idolize Gygax (I certainly find myself falling into this trap every now and again). Credit where credit is due, he pretty much single-handedly created the fantasy role-playing game and his influence on popular culture ever since is correspondingly macrocosmic. I would never deny this. But he was just a man, with a pretty low sense of humor, quite backward views (if you don’t agree just read some of the extended threads he features in on the web) and an often pretty poor taste in literature. And while he could pen some awesome adventures, he certainly couldn’t write fiction. And if you don’t agree with that, just try and read his Gord novels or, even worse, the later ones set in a fictional Ancient Egypt. You’ll find all the tedious humor and predictable misogyny you could ask for in those — having tried (and failed) to read them I’m not surprised for a second that Gygax enjoyed de Camp, but that doesn’t mean that we should be expected to anno 2015.

@29: I don’t know, for all his sins August Derleth did a much better job of promoting his chosen author… I think that the “logical fantasy” stylings of Larry Niven are far superior, even if some of his jokes are real groaners. (there’s one about a wizard using a fast atom-sized imp to keep his cave cool-readers familiar with thermodynamics may attempt to guess the punchline)

I encountered a couple of the Gygax novels that featured in Paizo’s Planet Stories line: yet again, my mind refused to retain any solid details.

@@@@@ 29

In matters of creating RPG, don’t forget Dave Arneson. It’s one thing to create rules for individual combat and put your players in the mission of invading a castle (what Gygax did early). It’s another thing for someone, in the part of a player of tactical game, not the judge, to alter the way the game is played so much that it becomes a role-playing game. Gygax was the firt true GM, but Arneson was the first true RPG player. Later Gygax would indeed contribute more to the popularity of RPGs. And I agree with his visions not always being adequate considering current tastes, and how the fiction he wrote wasn’t that good.

http://arsludi.lamemage.com/index.php/104/braunstein-the-roots-of-roleplaying-games/

Ryamano, cool, yes, Arneson matters of course. But he was a modest man and we know what happens to modest men. I still think Temple of the Frog is the best adventure ever written in terms of its actual background, NPC descriptions and the like. I’ve never played or DMed it, but I read it every now and again just for the pleasure of it.