When Dungeons & Dragons co-creator Gary Gygax published his now-classic Advanced D&D Dungeon Master’s Guide in 1979, he highlighted “Inspirational and Educational Reading” in a section marked “Appendix N.” Featuring the authors that most inspired Gygax to create the world’s first tabletop role-playing game, Appendix N has remained a useful reading list for sci-fi and fantasy fans of all ages.

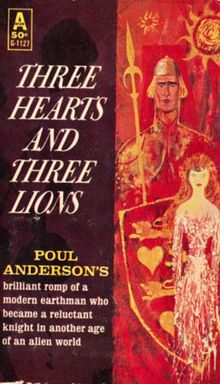

In Advanced Readings in D&D, Tor.com writers Tim Callahan and Mordicai Knode take a look at Gary Gygax’s favorite authors and reread one per week, in an effort to explore the origins of Dungeons & Dragons and see which of these sometimes-famous, sometimes-obscure authors are worth rereading today. Sometimes the posts will be conversations, while other times they will be solo reflections, but one thing is guaranteed: Appendix N will be written about, along with dungeons, and maybe dragons, and probably wizards, and sometimes robots, and, if you’re up for it, even more. Welcome to the second post in the series, featuring a look at Three Hearts and Three Lions by Poul Anderson.

To celebrate this awesome new series, Tor.com is giving away five gorgeous sets of D&D dice from Chessex. Check out the sweepstakes post for more information on how to enter!

Mordicai Knode: I think this might be the “least most famous” of the books in Gygax’s Appendix N. That is, I think people know it, like they know Tolkien (the “most most famous”) and Moorcock, but I don’t think it actually gets the readership it deserves. That is a real shame, since Three Hearts and Three Lions really acts like a roadmap to a lot of the concepts that informed the early days of Dungeons & Dragons. The book’s claim to fame, at least in terms of inspiration, are the paladin class and the troll’s regeneration—you know that great moment where you expose a newbie to a troll for the first time and they don’t know to kill it with fire or acid and it just keeps healing no matter what you do? Yeah, there is a great scene with that happening to our protagonist—but it also has a shapeshifting proto-druid with an animal companion and a tangible battle between Law and Chaos. It really gets overlooked—even the vast breadth of Jo Walton’s Among Others doesn’t mention it, though her protagonist does read a lot of Poul Anderson—and I think it deserves a wider audience.

Tim Callahan: I had never even heard of this book before I ordered it for this Gygaxian reread project. I remember reading a couple of short Poul Anderson books back in my college days, but they were purely sci-fi and that’s about all I recall about them. Three Hearts and Three Lions was completely new to me when I first cracked it open a couple of weeks ago.

And yet… after the opening WWII sequence kicked the protagonist into a mythical fantasy world, it seemed completely familiar. The whole book not only informs D&D in terms of the paladin and troll, but the alignment system is part of the understructure of Anderson’s work here. It’s a bit of Moorcock-lite with the Order and Chaos stuff in Three Hearts, but it’s closer to what Gygax would do with Lawful and Chaotic than what Elric navigated in the Moorcockverse. It’s familiar in other ways too, drawing upon Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court pretty heavily (and even making a direct reference to that classic novel), and pulling its hero from The Song of Roland. And if the three lead characters remind me of anything it’s the travelling companions in Spenser’s The Faerie Queene. The whole book is a tribute to other beloved fantasy tales.

Honestly, it looks like I didn’t enjoy it as much as you seem to. I liked playing the game of “oh, this part alludes to this other famous story,” but all the tributes and homages and allusions pulled me out of the actual narrative in almost every chapter. Three Hearts and Three Lions never really works as a story on its own. It’s a cut-and-paste job mostly, and Anderson doesn’t have a strong enough authorial voice in this book to give it any clear identity of its own.

It’s also weirdly cold and chaste. But maybe it just feels that way because we read this one right after that hot and sleazy Conan “Red Nails” story. Maybe I’m being too harsh on old Poul. Do you see what I’m saying about its faults, though?

MK: The problem with reading any classic story is that the tropes start becoming pillars of the more modern stories; I think some of what left you cold might be that the heavy recycling is sort of new & clever here, though in a current story it would be rather tired. It certainly isn’t the first to jumble everything together, but I think it is the first to jumble it all together with an engineer. That is, as I was reading it I felt like it was an arrow aimed at the heart of every doubting reader, a sort of tongue in cheek referendum on the suspension of disbelief. The magnesium knife that the faerie lord keeps in order to harm the others of his ilk who burn at the touch of daylight—burning magnesium releases UV radiation and that little touch could come out of any of the recent crop of Blade movies. He talks about lycanthropy using the language of Mendelian genetics and in my personal favorite the “curse” on a giant’s golden hoard is revealed to be radiation caused as a side effect of the creature’s transmutation to stone. The whole “bring a scientific explanation to the fantasy story” thing is rarely done with such elegance, if you ask me; normally I feel like it undermines the rules of the narrative, but here it is just sort of a running stitch reinforcing them.

Left cold, though? No way! The werewolf story, how great is that? I can’t get enough of that scene; it is maybe my favorite vignette in the novel. Followed shortly by the nixie, and here I think I have to half-way agree with you. The story is absolutely chaste, but I think that is really the point? It extols the virtue of courtly love & wistfully hearkens to a sort of old-fashioned—by which I mean, 1940s—idea of romance, while acknowledging the existence of sex and simultaneously condemning those ideas as silly. Sex is the primary tension between the characters! Holger wants Alianora, but thinks of her as being virginal—the unicorn doesn’t hurt that perspective—but Alianora clearly desires Holger. She’s sexually assertive & not slut-shamed, either; eventually the sexual tension is doomed by the romantic tension—they like each other, and since Holger doesn’t plan on staying in this fantasy world, they can’t be together without breaking both of their hearts. Meanwhile sexually available women—the elf Merivan, the nixie, and Morgan Le Fay, who is also a romantic rival to Alianora—dangle. I don’t know that there is a message… unless it is the dwarf’s befuddlement that Holger is making it too confusing by overthinking it!

TC: I can see how the courtly love stuff is part of that tradition, sure, and I really do think that it’s the juxtaposition with Robert E. Howard that makes it seem unusually chaste (I mean, most of these kinds of high-fantasy stories are almost unbearably innocent), but I didn’t feel any connection to the events of the story at all. The werewolf and nixie scenes lacked any kind of power for me. My favorite parts of the book, and the only parts that felt like they were truly alive—even in the fictional sense—were the moments when Holger was questioning what was real and what wasn’t. When he was trying to make sense of this world he found himself in. When he’s grappling with that, and then trying to figure out the subtleties of the shape-shifting female mind, and also play it cool around the mysterious Saracen, the protagonist is worthy of attention. Even the best fight scenes around those identity issues are more about Anderson playing around with fantasy tropes than moving the story forward in any meaningful way.

If we’re making the D&D connection, it’s like a beginning Dungeon Master’s approach to storytelling in this novel: a series of random encounters and an unimpressive mystery at the core. The big mystery? The reason Holger ends up pulled into this fantasy world? Oh, well, he’s actually a mythical hero named Holger and he has to defend this world from Chaos. Except, that’s the ending of the story, and he doesn’t so much as defend the world from Chaos in the rest of the book as he does wander around and stumble across stuff that Anderson wanted to write about (and add some goofy “hard science” explanations for, like radioactive gold can give you cancer).

Boy, I feel like I am tearing into Three Hearts and Three Lions, and I really didn’t hate it. But I certainly wouldn’t recommend it. It’s a curiosity at best.

I’m sure you’ll tell me how wrong I am about my criticisms, as you should, but I also have a topic to ponder that’s inspired by reading this novel: I wonder why the original D&D rules didn’t involve “regular” folks getting pulled into a fantasy world. Based on this novel and some of the others that inspired Gygax and friends, it would seem that the whole notion of a regular Earth man or woman finding themselves catapulted into a strange fantasy land would have been an obvious choice as part of the game, but it never was, not explicitly at least. Not until the 1980s D&D animated series. But I don’t think anyone played D&D with the cartoon as canon.

MK: You are right that the plot pulls him around, but again, I guess I just see that as a feature, not a flaw. I don’t disagree with a lot of what you are saying—it is more chaste and he is steamrolled by the greater plot—but I think those things serve the story. Right, Holger is Ogier the Dane and that is sort of just a bit of narrative railroading, but making it so lets you bookend the story with “generic epic saga”; you get that he’s some legendary hero, but whatever, this is about him as an engineer, this is about the series of weird stories that happen to him in the liminal space between being a hero of the past & a hero of the future. Here was where he got to be a person and straddle both worlds.

As to the pull from the real world to the fantasy—I’m not sure, actually, when that really became a “thing.” I know the early Gygaxian sessions often involved trips from the fantasy world to the real world—Dungeons & Dragons characters showing up in the western Boot Hill setting and coming back again, like Muryland—and I feel like the “play yourself!” campaign naturally occurs to everybody who plays the game at some point or other. “Hey, let’s stat ourselves up!” I don’t know about actual support for that in the game’s history, though; I suspect the witch-hunts based on wild conspiracy theories about Satanic cults and black magic put a stop to that, which is a shame; I’d sure like a crack at being myself in Middle World, or Middle-Earth or Oerth or whatever you call your fantastic setting of choice.

Tim Callahan usually writes about comics and Mordicai Knode usually writes about games. They both play a lot of Dungeons & Dragons.

The Troll and the radioactive petrification of same was my *favorite* bit. I “got it”, and really started to understand what Anderson was up to, then.

This has always (i.e., for about forty years) been my favorite Poul Anderson. And who cares if it borrowed heavily!

1. PrinceJvstin

Yeah, I have borrowed that sort of…inverted Star Trek technobabble? That is, in Star Trek, the MacGuffin is usually just a bunch of “sciency” words tossed together for magical effect. Reverse the tachyon’s spin to reveal the cloaked Romulan warbird! Whereas here, where the supernatural is (in part) a bunch of “magicy” words tossed together around a scientific effect. Fun.

I’m guessing the authors know, but many readers might not: This might well be described as Moorcock-lite, but this book actually predates all Moorcock’s Eternal Champion stuff. It might perhaps be more appropriate to say that Moorcock elaborated on Anderson’s theme of Order and Chaos. Though I’d guess they were both borrowing from something even older I haven’t read or am forgetting.

4. colomon

It’s true! Like I said to Tim, there is a lot in this book that might seem like it has been lifted from somewhere else, when in fact those places probably lifted it from here.

It’s interesting how books just vanish into obscurity. I looked for this book on Amazon, and there’s only one (used) copy available as an obscene price. No new copies, and no eBooks. (There is an audible version, though.)

About six months ago, I thought it might be interesting to read some of the older Hugo winning novels. An amazing number of those books are also unavailable as eBooks.

You think that in today’s world, everything that’s ever been written (other than Aristotle’s Comedy) is available. And every now and then, you’re reminded that’s just not true.

6. fcoulter

Try looking again; I just looked at a few used vendors (including Amazon) & they had some used versions available. Though it is weird how things can fall through the cracks; I hope the rise of print on demand publishing will help with some of that, in the oncoming future.

You mentioned Mark Twain’s “A Connecticut Yankee at King Arthur’s Court” as one of Anderson’s inspirations for “Three Hearts and Three Lions”. It is also worth noting that Anderson did another take on that durable fantasy (“Go back in time. Impress the primitives with modern technology! Thus becoming famous, powerful and wealthy!”) in his short story “The Man Who Came Early”.

That story, for those who haven’t read it (SPOILER WARNING!) involves a 20th Century American GI stationed on Iceland who is dropped back through time to 10th Century, Viking Era Iceland. He speaks modern Icelandic so he can communicate with the local Norse. Once he figures out when and where he is, he thinks he can do the Connecticut Yankee stunt. He talks of making himself a king. But then he runs up against the realities of medival technology; particularly in a backwater like 10th Century Iceland. The narrator describes him mumbling in despair: “You don’t have the tools to make the tools to make the tools…”. Instead of becoming wealthy and powerful, he winds up dead and soon forgotten.

Another detail: at the end of “Three Hearts and Three Lions” the hero Holger Carlsen is said to have vanished mysteriously. It is implied that he had used magic to return or try to return to the world he saved and to the swan may Alianora. Whether or not he succeeded is left unknown.

Then Holger got a cameo appearence in “A Midsummer’s Tempest”, another of Anderson’s novels, years later. The heroes of that novel find refuge in a magical inn, “The Old Phoenix”, and Holger is another of the guests. He has been travelling across world lines without finding the universe he seeks. Fortunately, another guest at the inn comes from a world line where magic is a form of engineering (Anderson’s “Operation Chaos” and “Operation Luna”). She gives Holger a cram course on transworld transporation techniques with a proper mathematical grounding.

So we can hope he made it back to Alianora in the end.

Mordicai and I read this Poul Anderson book and had our discussion a while back (sorry to spoil the behind-the-scenes illusion that we write these “live” — we don’t), and now that I’ve read a whole lot more of the authors in Appendix N, Poul Anderson actually ends up as one of my favorites. “Three Hearts and Three Lions” might even be in my Top 10 Appendix N selections.

I was too hard on the book! I didn’t know what I was yet to encounter.

8. JohnnyMac

Ha! We’ll get to something similar in Lest Darkness Fall…but that brings a whole other conversation up that we’ll have to wait for…

Mordicai @11, I look forward!

9. JohnnyMac

That bit about Midsummer’s Tempest is giving me, as the kids on Tumblr say, “feels.”

10. TimCallahan

You were hoping they’d all be Dune & Lord of the Rings, weren’t you.

Three Hearts and Three Lions was originally a novella in F&SF in 1953, where Moorcock’s first Elric story was not until 1961. So the Order/Chaos dichotomy was borrowed in the other direction. Of course D&D borrowed Law/Chaos from Moorcock’s formulation.

For some reason, Anderson always appealed to my head more than my heart. And this story was just a bit too grim for my young tastes. But I can certainly understand why it is on the D&D list, because it is a very well written fantasy story, and brings a more modern-feeling logical and methodical approach to the world of magic.

That is not to say that Anderson is not a great writer. His tales of David Falkayan, Nicholas Van Rjinn and especially Captain Sir Dominic Flandry are among the best science fiction ever written.

Mordicai @13, forgive me but suffering, as I do, from a severe case of ignorance of modern social media, I don’t get your reference to Tumblr and “feels”. Clarify, if you would be so kind, for someone far behind the curve technologically.

AlanBrown @16, I think we can agree that Poul Anderson was one hell of a writer. He did have well developed streak of Scandinavian grim and gloom that cropped out in his stories from time to time (i.e. “Journeys End”, “The Pugilist”). At the same time he also often displayed a mid-century American optimism that we don’t see much anymore.

He earned his living at his typewriter for more than 50 years and he never forgot, as he put it, that he had to convince his readers that spending their money on his books was a better value than, say, buying a six pack of beer.

@18

I like Anderson in his “Scandinavian grim and gloom” ways. That’s why I vastly prefer his “The Broken Sword” which is an undeservedly forgotten classic above his medieval style catholic stuff like Three Hearts and Three Lions.

I would guess that D&D avoided the person pulled from our world to the fantasy world because it was so closely connected to John Carter. Not that Barsoom is bad, but it wasn’t what they were doing.

Also, Tolkein’s extremely rich worldbuilding seems like a better match to the whole enterprise.

@9

IIRC, Valeria (herself a future cameo from Operation Chaos) refers to Holger’s grimoire as a “guided missal”.

@mordicai and Tim Callahan: Good post, though I strongly disagree with the use of the phrase “Moorcock-lite”. If anything, Moorcock’s fantasies are Anderson-lite (+Howard, Leiber, Vance &c).

I do like this book, though it has several problems. It was, after all, Anderson’s second novel (serialised 1953) and I got the sense he was still learning the craft while writing it. In particular, his 1954 fantasy novel The Broken Sword (not the edited version from the 70’s, the original version) surpasses it in many ways.

I’m not sure how useful The Broken Sword is for D&D (I’ve never played it) since our hero doesn’t have a great amount of free will but I consider it to be one of its era’s most significant fantasies and the novel is worth reading just to see where the darker, more modern fantasies came from in the first place.

@16: The Technic History was my first Anderson. That’s a series that deserves a good, long, Tor re-read…

17. JohnnyMac

Ha ha ha, being called on the carpet to explain internet shorthand is always tricky. I guess “feels” applies to a wave of emotion, usually one that is sort of mixed with melancholy (or, since it is the internet, sex). So “feels” could be something like, seeing Alison Brie photoshopped as Captain America– awesome & also…hot– or in this case, a sort of sadness tinged with a sprig of hopefulness.

@JohnnyMac and Mordicai: I always find Know Your Meme helpful, in these situations :)

16. AlanBrown

&

18. JohnnyMac

&

19. Lieven

Is this gloomy? I guess I didn’t feel like it was, which probably says something about my own sensibilities. When I think “grim” though, I generally think about 90s comics, & gore & posturing for the same of seeming adult (while only seeming juvenile), or I think of the tendency of dramas to just go with Feel Bad plots where everything bad that can go bad does go bad. This isn’t too grim! Maybe a little star-crossed but hardly a tragedy!

Whenever I read stories in the “scientific fantasy” sub-genre (which is not quite “science fantasy”), I always flash back to the Harold Shea “Incomplete Enchanter” works of Fletcher Pratt and L. Sprague de Camp, starting back in 1940 in Campbell’s Unknown magazine. Three Hearts and Three Lions fits in with those stories very closely.

Also, it contains the best punchline to “Why did the chicken cross the road?” of which I have heard: “Because it is too far to walk around.” Though the dwarf’s allegorical/spiritual interpretation is pretty funny, too.

26. Eugene R.

Very much unrelatedly, but the last of Alex Bledsoe’s Eddie LaCrosse books had an “interrupting cow” joke that make me laugh.

Mordicai @23 and BMcGovern @24, thank you! I get it now, more or less (which is about as much as I get anything nowadays).

Mordicai @25, to clarify what I said above (@18) about Anderson’s “…well developed streak of Scandinavian grim and gloom” was not meant as a specific reference to “Three Hearts and Three Lions”. I would say that story is more an example of what I refered to as his “…mid-century American optimism.” Not only do the good guys win but Holger uses his American engineering education to defeat various medieval supernatural menaces: he calculates that throwing a helmet full of water down the dragon’s throat will result in a steam explosion, he figures out how to ignite magnesium underwater to defeat the nixie, etc.

For “…grim and gloom”, I was thinking of the stories I cited as examples of that tendency in Anderson’s work. And they are grim; don’t read them if you are feeling depressed. He did enough of these that I believe it is fair to say that it is an important aspect of his work. For another example, novel length, see his “Let the Spacemen Beware!” AKA “The Night Face.”

On the other hand, Poul Anderson had a hell of a sense of humor as well. One of my favorites in his comic work is “The Homemade Rocket” AKA “A Bicycle Built for Brew”. Which does involve, yes, a beer propelled rocketship. With bicycle powered electric systems. And, strangely enough, it is designed, built and piloted by a space faring Dane.

Tekalynn @21, your comment inspired me to dig out my copy of “A Midsummer Tempest” and I found that Valeria scornfully refers to Holger’s grimore as “…an unguided missal.” Anderson did love his wordplay.

& I didn’t even mention Cortana! I sure like magical swords; even more so when they are historical! Which, now I’m thinking about

Eterne, from The Wizard Knight, which is one of my favorite purely fictional swords. Or oh wait, no, my favorite sword is

Gurthang nee Anglachel, probably, now that I think about it.

Wow, I had only read Anderson through “The Broken Sword” and didn’t look beyond that. I didn’t realize how much sci-fi he wrote.

32. theleftdm

Reading Among Others really pounded it home. Which, by the way, if you haven’t read Among Others, you should.

I can only echo the two important points brought up by several others: a) the Law/Chaos trope originated here, and that’s where Moorcock (and Gygax) got it from, b) The Broken Sword had less of a specific influence on AD&D but was nevertheless a very significant influence on the … I don’t know, flavor? color? of the game. And isn’t Anderson’s The High Crusade (also listed in Appendix N) his take on A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court?

Oh, for what it’s worth, Gygax’s son Ernest Gary Gygax Jr. (the Tenser), assures me that Anderson’s ´´Ensign Flandry´´ Series was also much beloved by his father.

@34: Is “atmosphere” the word? Anderson also attacked Twain’s “modern-timer outwits backwards past folk” plot in “The Man Who Came Early”, which I recommend. It’s interesting to hear that about the Flandry books, which were also an influence on classic Traveller.

Atmosphere, thanks! ;-) I guess the ´´Ensign Flandry´´ Series didn’t make it into Appendix N as it’s sci-fi (I haven’t read it myself), though it’s very clear that back in the days of Appendix N, the modern (post-Tolkien’s imitators?) delineation of what constitutes fantasy was far more flexible than it is today. In case you’re interested, here are two more (as I understand it) sci-fi addtions to Gygax’s Appendix N:

Laumer, Keith. GALACTIC ODYSSEY; ´´Retief´´ Series; et al.

Vance, Jack. ´´Demon Princes´´ Series

Those two fine series are also on the list of Traveller influences: http://www.blackgate.com/2013/10/08/appendix-t/

Read all of these in a short space of time and you may recreate my average state of mind when younger.

I find it interesting that in discussing the idea of a protagonist returning to the mundane world in fantasy fiction no one has mentioned Oz or Narnia. It was, after all, an intentional contrast to the latter that in part led Tolkien to engage in the world-building for which his works are famous.